The Swinehart Farm – part 1

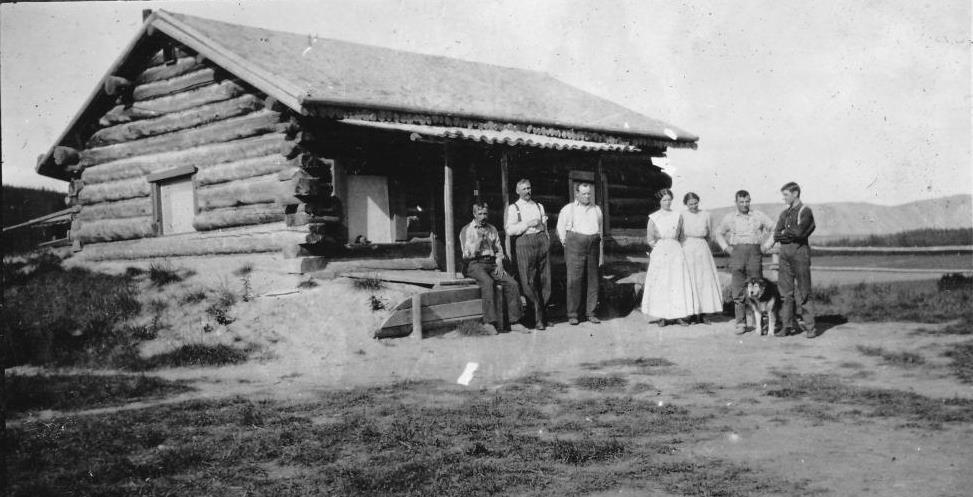

(Heather & David Ingrams collection)

Discovering the Swinehart Farm

There is a long-abandoned and overgrown farm in the bush near Fort Selkirk that seems to be little known and overlooked in Yukon history. It was a pioneer farming enterprise established by William Swinehart and his family during and following the Klondike gold rush. It operated for 16 years until Swinehart died while working in his field. He is buried at the Yukon Field Force cemetery at Fort Selkirk.

Some sources referred to Swinehart as “the pioneer farmer of the Yukon” and “the potato king of the Yukon”, titles that may ignore others who were doing similar things at the same time. Nevertheless, they are indicators of Swinehart’s status and role in early Yukon agriculture.

I have known of the Swinehart Farm for many years from my time spent with the Bradleys at Pelly River Ranch, but not much seemed to be known about it. Oral history projects conducted at Fort Selkirk in the 1980’s make it clear that the farm was known locally, but it is virtually absent from published reports on early Yukon agriculture. When I began researching the Swinehart Farm a few years ago, three very helpful things fell into place.

The first was finding the legal survey plan and field book for the farm property, which were dated August 3, 1902. The parcel was 80 acres and “surveyed for W.H. Swinehart”, leaving no doubt it was the right property and where it was located. A further look at the lot in greater context showed that it still exists, totally surrounded by Selkirk First Nation land except for a road right-of-way surveyed out to maintain legal access to the property. This meant the lot was perhaps still owned by somebody, and a little more digging confirmed it, an interesting situation that will be discussed later.

(Google Earth)

The second event was very fortuitous, when a lady in California named Susan Coltrin posted a query on Murray Lundberg’s ExploreNorth blog looking for information about the Swinehart Farm. Ms. Coltrin, a history teacher who was married to a Swinehart descendant, had a keen interest in the Swinehart Farm from both historical and genealogical perspectives. Thanks to Mr. Lundberg’s assistance, I was able to communicate directly with her, which resulted in an exchange of information about the farm and family, including historically valuable photographs.

The third good thing was making contact with Heather and David Ingrams of Ottawa, who are great-grandchildren of William Swinehart. They also provided valuable photographs of the Swinehart Farm, the Fort Selkirk area and other locations, as well as some additional family information.

With these photos and information, things had lined up for a visit to the Swinehart Farm to learn what I could on site. I have been there several times, by three modes – walking, ATVing and snowmobiling. Two of the trips involved hauling a long ladder there to get into the tops of trees for views of the surrounding hillsides. This was to try to match up hill profiles that appeared in some of the old photos in order to prove that they are of the Swinehart Farm. A later trip to the farm involved the use of a drone, rendering the previous ladder efforts unnecessary and a little comical.

(©Neal Allison photo)

I have to acknowledge the interest and efforts of Ron Chambers, Dale and Ken Bradley, and Neal Allison in accompanying and assisting me on the trips to the Swinehart Farm. I’m very grateful to have people like this willing to humor me in carrying out these ventures.

In addition to the on-the-land explorations, I have done archival, genealogical and other research to try to piece together tidbits of information to help tell the story of the Swinehart Farm. Here is the story as I have it so far.

(Yukon Government photo)

From Wisconsin to Alaska (1896 – 1898)

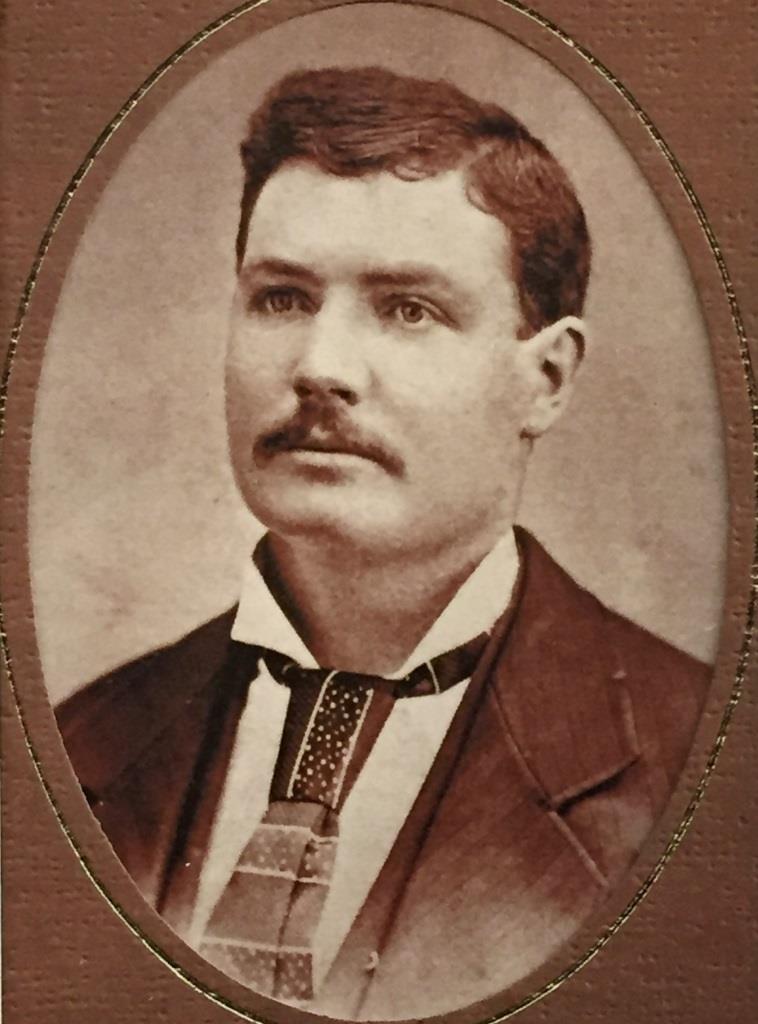

William Swinehart was born into a farming family in Wisconsin in 1855, but his early adult years did not foreshadow his future as a Yukon pioneer farmer. He attended a classical and musical academy, graduated from a business college, and became a bookkeeper and a county treasurer. By the late 1880’s William and his wife Rhoda had four children, a son and three daughters. Rhoda died in 1889 shortly after the birth of the last daughter, who was subsequently named Rhoda.

(provided by his great-grandson William Coltrin, June 2019)

In February 1896, William and Guy, his 14-year old son, left for Juneau, Alaska, leaving the three daughters behind in Wisconsin, likely in the care of their Swinehart grandparents. William went to Juneau to join his younger brother George, who was established there as editor and publisher of the Juneau Mining Record newspaper. Guy attended the Sisters of St. Ann School in Juneau for the 1896-97 school year.

Sometime within the next year and a half, William’s two oldest daughters, Leta and Vivian, at aged 17 and 12 respectively, came to Juneau and attended the Sisters of St. Ann School for the 1897-98 school year. Vivian remained in Juneau for the following two school years, but Leta returned to Wisconsin and rejoined her little sister Rhoda, who had been left alone with her grandparents.

In the summer of 1897, after boats loaded with Klondike gold arrived at Seattle and San Francisco, the gold rush was on. In Juneau, the brothers William and George Swinehart and William’s son Guy mobilized to head for the goldfields the following spring. They were joined at some point by two other men, a fellow Wisconsinite named William Thompson and Ham Kline, a brother-in-law of William Swinehart. The 1901 Canada Census shows them all arriving in the Yukon in April 1898 and still being together at Fort Selkirk three years later, so it is reasonable to assume they travelled into the Yukon together.

Into the Yukon (1898)

In the spring of 1898, the Swinehart entourage joined the gold rush horde along the Chilkoot Trail and into the Yukon. On April 3 they were at Sheep Camp on the Trail when deadly snowslides occurred that claimed around 60 lives. The Swinehart party made it as far as what is now known as Carcross before they had to wait for the ice to go out of the lakes.

While most gold rush stampeders were bringing mining-related equipment and supplies over the trail, the Juneau newspaper man George Swinehart brought printing equipment. While waiting for the ice to go out, he put out the one and only issue of the Caribou Sun on May 16, 1898, one of the earliest newspapers printed in the Yukon. When the lakes and Yukon River were open to travel, George headed for Dawson City rather than go to Fort Selkirk with the rest of his party. On June 11, 1898, he published one of the first Dawson newspapers, called the Yukon Midnight Sun.

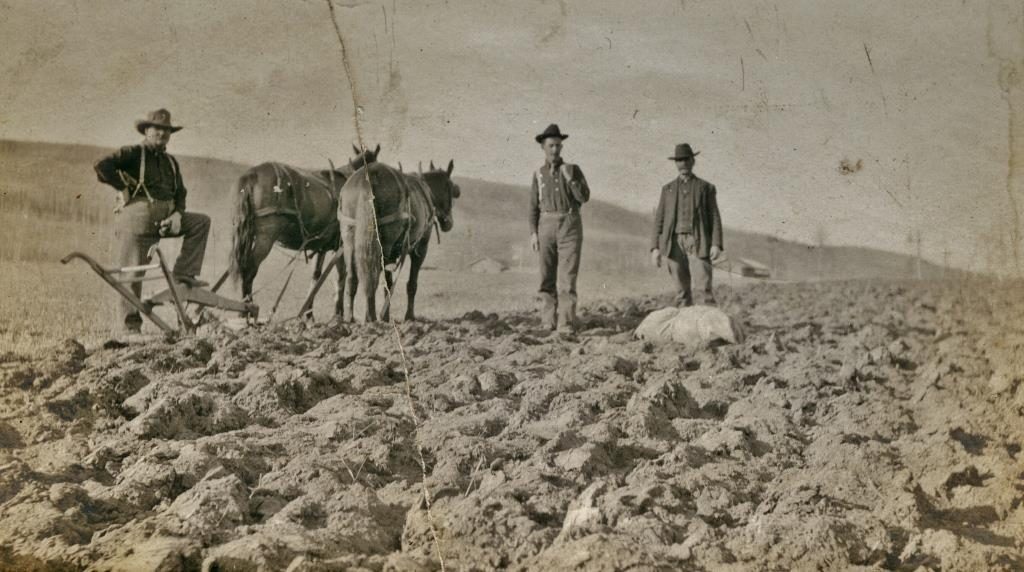

Like his brother, William Swinehart apparently also brought equipment for a Klondike venture other than mining. In 1914, in a letter to his Wisconsin home town, he wrote this: “I came to Yukon in 1898 from Juneau, Alaska … with the big gold stampede of over 20,000 people on the trail at the same time. I claim distinction as being the only man in that big crowd who came for the purpose of farming. I had four horses, plows, harrows, seed potatoes, cultivators, and provisions for a year and a half. In fact, our party was quite a curiosity because we were not seeking gold.” It would have been a sight to see all this farm equipment and supplies being transported over the Chilkoot Pass and then on some sort of watercraft on the journey across the lakes and down the Yukon River.

A 1903 Yukon Sun newspaper article told it differently, that William Swinehart intended to go mining, but decided to venture into farming after seeing the prices being paid for hay, grains and garden produce in the Yukon. Where this information came from is not known, but whatever the case, when the Swinehart party arrived at Fort Selkirk on or about June 15, 1898, they stayed to pursue the agricultural possibilities they saw there. About three kilometers into the bush west of Fort Selkirk, they set to work clearing land, building a house and barn, and digging an irrigation ditch from a nearby drainage.

(Susan Coltrin collection)

Updated October 7, 2023