(Gord Allison photo)

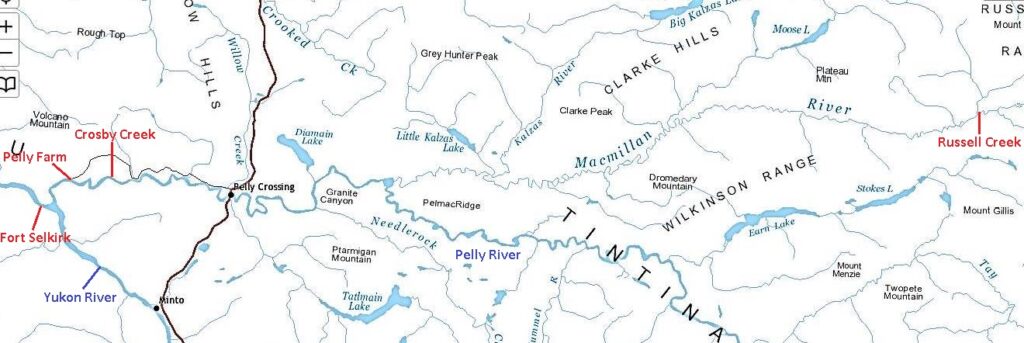

On the Pelly River Ranch road about 40 kilometers in from Pelly Crossing, you drive over a culvert containing a small creek. When you travel down the Pelly River from Pelly Crossing, after about 37 kilometers you go by the mouth of that same creek and probably would not notice it. This is Crosby Creek, the name recommended by eminent geologist Hugh Bostock in honor of George Crosby, who came to the Yukon at the time of the Klondike Gold Rush and homesteaded near the mouth of the creek.

George Crosby was no spring chicken when he came to the Yukon. He was born on November 27, 1856 in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, one of eleven children in a farming family. At some point in his adult life he began moving westward, and in 1891 was working in a sawmill in the Upper Kootenay region of British Columbia. A Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) report in 1938 said that he had resided continuously in the Yukon for 39 years, suggesting he came in 1899 when he was going on 43 years old.

Trapping on the upper MacMillan River

Crosby’s initial time in the Yukon was not associated with the creek that bears his name. In the early 1900s he went trapping in the area of the fork of the MacMillan River, a tributary of the Pelly River. This region, perhaps known most commonly as Russell Creek for a trading post and mining activity that were there, is located 300 river kilometers upstream (east) of present-day Pelly Crossing. Despite its remoteness, Russell Creek was the center of an active area at that time for trappers, big game hunters and a few placer miners. How and why Crosby ended up there is not known, but it evidently offered him an opportunity and perhaps a lifestyle he was seeking, and he was to have a recurrent connection with this area over the course of his life in the Yukon.

(Yukon Government Lands Viewer)

Crosby and others like him on the MacMillan River may have lived their lives there in obscurity had the activities of the area not been recorded in books such as big game hunters Frederick Selous’ Recent Hunting Trips in British North America (1907) and Charles Sheldon’s The Wilderness of the Upper Yukon (1911), as well as miner, trapper and hunter Nevill Armstrong’s Yukon Yesterdays (1936) and After Big Game in the Upper Yukon (1937).

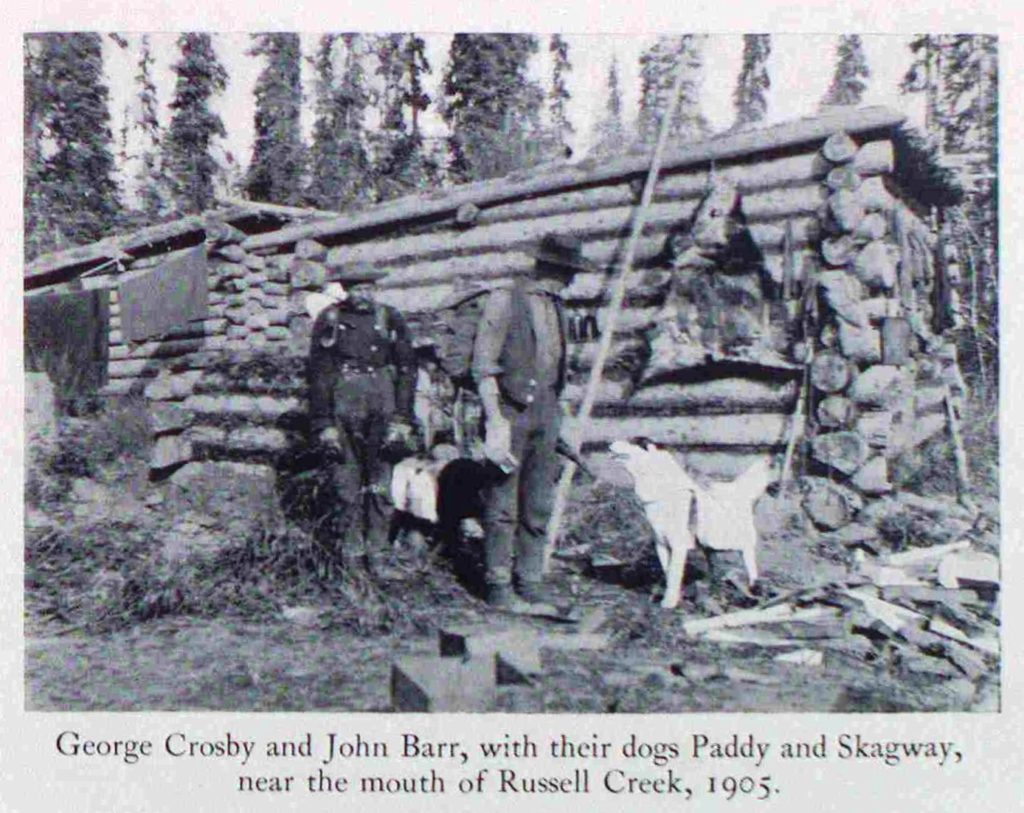

In 1904 all three of these authors encountered Crosby and his trapping partner John Barr in the Russell Creek area where they had been trapping the previous winter. Selous described Crosby and Barr as “… most excellent fellows, full of intelligence, and ready to give any information or assistance in their power …”. Armstrong’s After Big Game book contains the only photograph I have come across of George Crosby, shown at left below.

Nevill Armstrong, After Big Game in the Upper Yukon, 1937, p. 49)

The books by Armstrong, Sheldon and Selous, as well as one by Stratford Tollemache called Reminiscences of the Yukon (1912), provide some insight into the lives of trappers in that area at that time such as Crosby. These books show that while it may appear to have been a romantic life of wilderness living and independence, in reality it was also a life of hard work, much of it in cold weather.

For the trappers of the upper MacMillan River, the remoteness provided additional challenges. In May when the river became free of ice, they loaded their winter fur catch into boats and paddled, rowed or poled them down the MacMillan, Pelly and Yukon Rivers to Fort Selkirk. There they sold their furs and purchased provisions for the next year, then had to get their loaded boats the hundreds of kilometers back upstream. This was grueling work, day after day for a month to six weeks of poling and lining the boats (pulling by rope, often from in the water) in varying weather and river conditions. They had to be back to the upper MacMillan by late summer to prepare their cabins, trapping trails, firewood supply, and meat for themselves and their dogs for the upcoming season. This annual round meant that they generally spent ten months of the year in their trapping area.

The Frozen Toe

During the winter of 1908-09, Crosby had a traumatic experience, as told in Nevill Armstrong’s After Big Game in the Upper Yukon. On a very cold morning Crosby set out on his trapline with a toboggan pulled by his dog Faro and, when nine miles away from his cabin, began to realize that his right foot was freezing. This was a potentially dire situation, so he unhitched Faro from the toboggan and headed back toward the cabin. After getting it warmed back up, he took off his moccasins and found all the toes on his foot frozen.

Crosby thawed out his toes in cold water, an agonizing process, but that did not end his troubles. His big toe began to fester and deteriorate, and after a few weeks the bone was showing. He decided that he would have to remove the toe to prevent gangrene from spreading into his foot, and pondered how to do this cleanly and not so crude as to make him faint. The answer was a pair of strong scissors, with which he managed to cut off the toe, apparently doing a neat job of it. He used vaseline for an antiseptic and pieces of handkerchief for bandages and the toe ended up healing very well.

Crosby had to fend for himself for a month awaiting a scheduled visit by his partner John Barr, whose trapping base was more than 70 kilometers away. His bad foot caused him to hobble around outside in the cold to get wood for his stove and snow to thaw for drinking and cooking. He did not even have the companionship of Faro, who had not followed him home as he expected. When the dog didn’t turn up after a few days, Crosby presumed the wolves had got him.

John Barr showed up at the cabin on the scheduled day and heard Crosby’s story. He went out to retrieve the toboggan and its contents and to see if he could find any sign of what happened to Faro. On reaching the site Barr found the dog alive and well beside the toboggan, having remained there faithfully for a month with no food, waiting for his master to return.

In the early summer of 1909, Crosby’s foot was still on the mend and he appeared to be suffering from scurvy when Armstrong encountered him and John Barr on the MacMillan River heading downriver. Crosby’s condition may have prompted him to live closer to civilization, as a note from Pelly Farm shows Crosby being paid in October of that year for five months work at $78/month. The 1911 Canada census listed Crosby on the Pelly River along with six other people who were all connected to Pelly Farm.

Also in 1911, the RCMP in Dawson City received a letter from Crosby’s brother Arthur in Nova Scotia asking for any information about George, as the family had not heard from him for about 12 years. They had heard there was a George Crosby in the wood business across the river from Fort Selkirk who had been hunting up on the MacMillan River. At some point George must have established contact with his relatives because near the end of his life 30 years later he named a niece as his next of kin and knew where she was living in Alberta.

Homesteading on the Pelly River

After 1911 Crosby’s activities are unknown until March 1917, when in his 61st year he applied for a homestead of 160 acres at the mouth of Garnet Creek (later to become Crosby Creek), about 21 kilometers up the Pelly River from its confluence with the Yukon River near Fort Selkirk. It is conceivable that from his many trips past there on the river he noticed the potential of this location for an agricultural endeavor.

An inspection report by the Crown Timber and Land Agent concluded that the land was suitable for agriculture and had no valuable timber, only 75 cords as estimated by Frank Chapman of the Pelly Farm. By July Crosby was granted entry to the land to remove the timber and begin the required work for obtaining his homestead.

An inspection report in August 1920 showed that Crosby had resided at the homestead continuously since 1917 and had a log house and stable built and three acres under cultivation, with 15 more acres cleared. By that time, in addition to the developments, Crosby needed to have the land legally surveyed to meet the requirements of the homestead regulations and to obtain ownership.

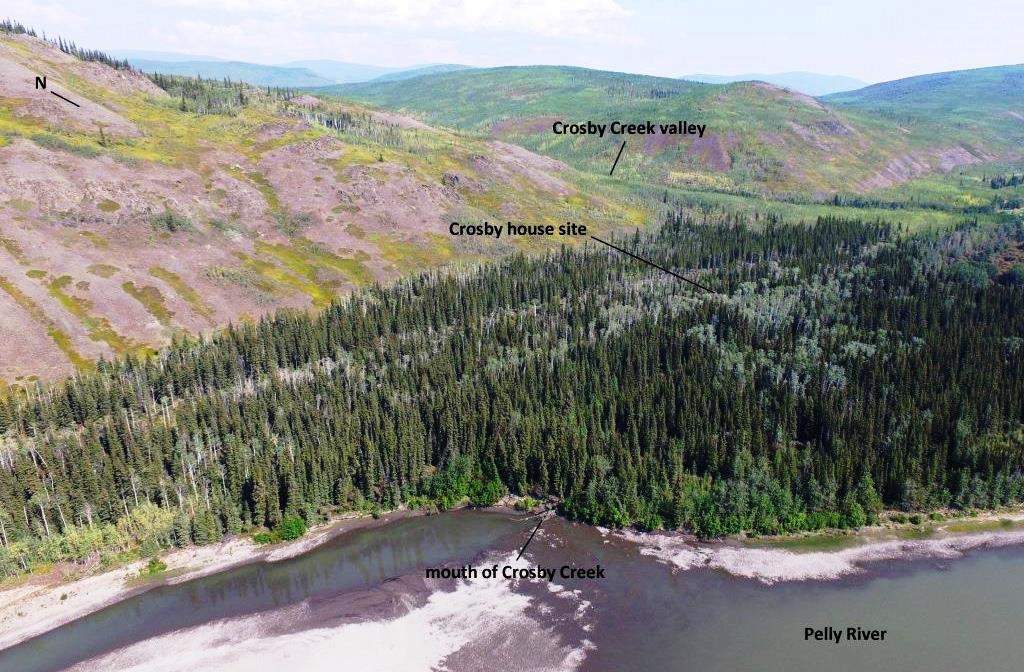

(Gord Allison photo)

(Heiko Nyland photo)

In January 1921 Crosby wrote a letter to the government suggesting he may cancel the homestead because of the difficulties of finding a surveyor and the expense of the survey. The government replied that it did not want to put undue pressure on him and suggested he apply for an extension of time to have the survey done. Crosby did so and also stated that “I am residing on the homestead … except a few months working down to Pelly Farm, have done a great lot of work here”.

Over the next couple of years there were more letters from the government about having the land surveyed, with no response from Crosby until April 1923, when again he declared that he could not afford the cost of it. By then he had five acres seeded to sweet clover and brome grass, 30 more acres cleared and ready for seed, and three acres of potatoes and other vegetables. He also said that he had been working at Pelly Farm that winter. Later that summer, Nevill Armstrong recorded that Crosby was back up on the MacMillan River to trap again.

Another extension of time to have the land surveyed was granted to Crosby, but there was no further correspondence from him. His homestead file laid dormant until June of 1932, when a government land agent reported that Crosby had returned to Fort Selkirk after being up the MacMillan River, and had abandoned his Crosby Creek land years ago. Perhaps a man of his independence had not been able to tolerate the idea of owing something or having an obligation, and was willing to leave behind the homestead he had worked so hard to develop. Whatever the case, Crosby’s file was subsequently closed and the homestead cancelled.

Crosby’s Mark

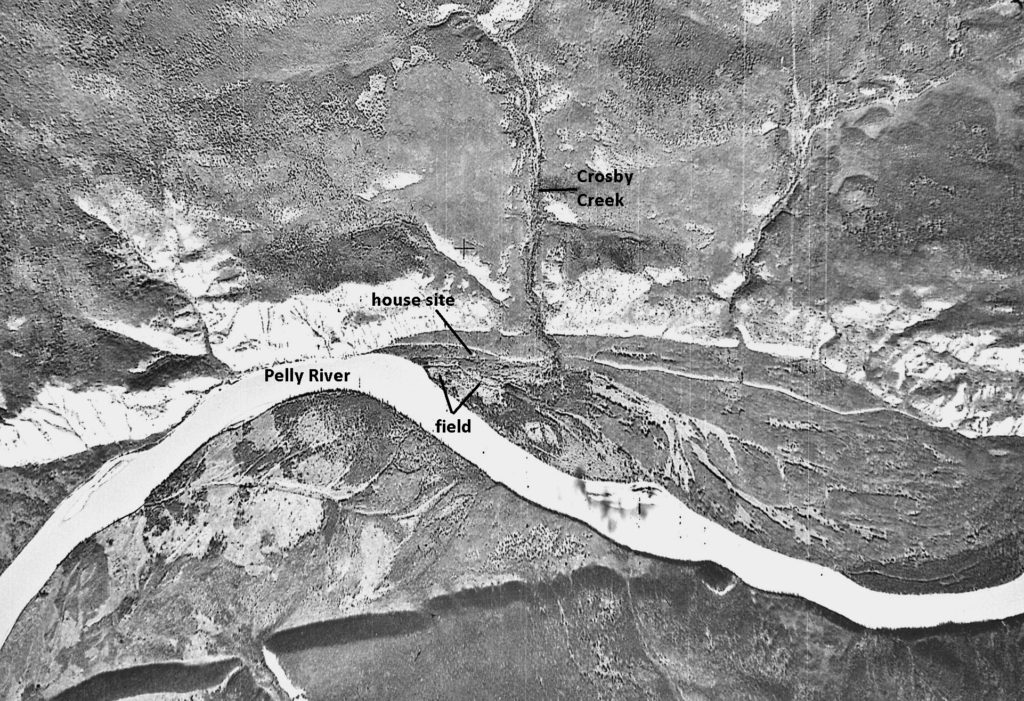

There is no record or indication of anybody taking over Crosby’s homestead after he left it, and it gradually went back to nature. His field, which would have been cleared by hand, is no longer readily discernible from the air or on the ground, but it shows up on older air photos of the area.

(National Air Photo Library, A12183, #179)

From the evidence still remaining on the land, the ‘great lot of work’ Crosby referred to in his letter to the government may have been an understatement, especially considering his age when he started developing the homestead. The basement/cellar of his house with substantial wood cribbing still remains in place and holding back most of the dirt 100 years later.

(Gord Allison photo)

Crosby’s house was sold in 1940 to Stanley Jonathan, who dismantled it, rafted the logs to Fort Selkirk, and reassembled it there. The solidly-built log house with dovetailed corners and broad-axed walls is now under the care and maintenance of the Fort Selkirk historic site, and provides lasting evidence of Crosby’s industriousness and craftsmanship.

(Yukon Government photo)

The most enduring testament to Crosby’s work at his homestead site is a hand-dug irrigation ditch running for close to a kilometer from a point of elevation further up Crosby Creek. I first heard about Crosby’s place many years ago from Dick and Hugh Bradley of Pelly River Ranch, and my main memory is of them talking about the ditch. They must have been impressed by the hard work it would have taken as well as the engineering skill to maintain a consistent downhill grade along the whole distance of it. Appearing to have been at least a foot deep when it was dug, the ditch gradually angles down along the side of a terrace to the level of Crosby’s house, probably to supply water to his potato and vegetable gardens.

(Gord Allison photo)

The Final Years

Crosby’s old stomping grounds on the MacMillan River evidently drew him back there after he vacated his homestead on the Pelly River. He was noted by Nevill Armstrong to be on the MacMillan in 1923 and 1925, in the latter year being hired by Armstrong to assist with prospecting and mining on Russell Creek. This was after Crosby had spent the previous winter trapping there when almost 70 years old. Armstrong also mentions Crosby bringing him 40 pounds of potatoes he grew in a garden on the MacMillan River.

When Crosby left the MacMillan is not known, but records show he was in Fort Selkirk in 1932. At some point between then and 1937, he stayed there to live.

Crosby’s life changed dramatically late at night on February 3, 1938, when he was 81 years old. His cabin in Fort Selkirk burned down after he dropped a match onto his mattress and caught it on fire. He tried to beat it out with his hands without success, then clad only in underwear and almost overcome by smoke inhalation, he made his way to the local store for help. The fire was impossible to extinguish and everything including Crosby’s effects were destroyed.

The RCMP report of this incident prepared by Constable G.I. Cameron, in command of the Fort Selkirk detachment, labelled Crosby as an ‘Indigent’ (meaning needy). The report stated that the fire had left Crosby “..completely destitute … he is almost blind and very infirm physically, the minor burns and shock he received left him in a state of almost complete collapse … it has been necessary for an attendant to be constantly with him…”.

A story related to me by Cst. Cameron’s daughter Ione Christensen, and which is also told in Joyce Yardley’s book Yukon Riverboat Days, is almost certainly about the Crosby fire incident, although I have no proof of it. Cst. Cameron’s wife Martha went to the fire and as the roof started to collapse, a box came sliding off that contained cookies and other goodies she had given the old man for Christmas. He hadn’t eaten any of them, so she was somewhat miffed and threw the box into the fire. The next day the man came by tearfully lamenting the loss of his Christmas gift, saying that it was the first time in his life anyone had given him something nice, and that he would just look at the goodies because they were too pretty to eat. Martha then had to get busy and make him a new Christmas box.

A couple of days after the fire, Cst. Cameron sent a telegram to the RCMP headquarters in Dawson City saying that Crosby could not care for himself and wished to go to the Dawson hospital. He was not fit for overland travel and so a few days later when a scheduled White Pass plane arrived, he was transported to Dawson.

So what became of poor old destitute, infirm, almost-blind George after he got to Dawson City? The tough old man lived in the St. Mary’s Hospital for another four and a half years, almost to age 86. There he racked up a bill of $6,804 for 1,701 days of care at $4.00 per day. The only payment made on the account during that time was $425 in May 1942, perhaps from the sale of his Crosby Creek homestead house.

A letter from the sister superior at St. Mary’s Hospital to the Public Administrator advised of the death of George Crosby early in the morning of October 4, 1942. He had no personal belongings. George was buried in the Hillside Cemetery in Dawson City, the location of his grave now unknown.