(Gord Allison photo)

Introduction

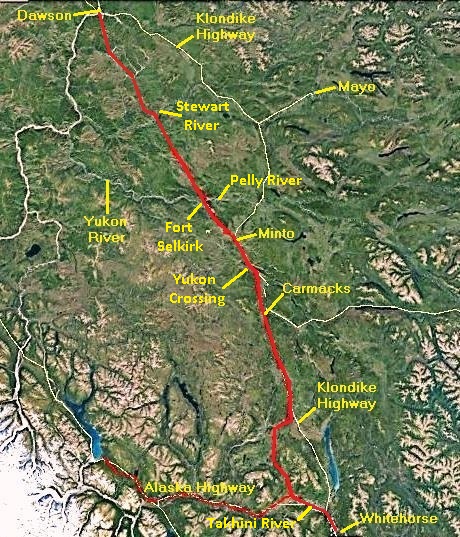

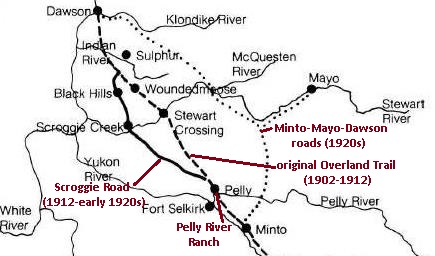

In 1902 a 330-mile winter road, known most commonly as the Overland Trail, was built between Dawson City and Whitehorse to provide a reliable transportation link between the two communities during the season when the Yukon River steamboats were not running. Together with the railway built two years previously to Whitehorse from the port of Skagway, Alaska, the new road would facilitate the movement of mail, people and freight between the coast and the Klondike region during the winter.

Parts of the Overland Trail laid the groundwork for the present North Klondike Highway and a bit of the Alaska Highway, and some sections are now used for resource access or recreational and subsistence activities. Other parts remain unaltered and intact, still persisting on the landscape as part of the Yukon’s tangible historic record.

The Transportation Setting to 1902

At the turn of the 20th century, the Klondike gold rush was over and the Yukon’s population was declining. In Dawson City, the Yukon’s capital at the time, there were still over 9,000 people in the 1901 census, with many more thousands living along the creeks of the surrounding goldfields. This amount of people and activity relied on a transportation system that could deliver the required provisions, supplies and equipment from the outside.

Completion of the White Pass & Yukon Route railway from Skagway to Whitehorse in late July of 1900 had caused a major transportation shift in the southern and central Yukon. Freight from southern Canada and the United States could be brought much more readily to the Klondike from Skagway, a trip of less than half the distance of the previous route up the Yukon River through Alaska. Many more steamboats were put into service on the Yukon River between Whitehorse and Dawson to adapt to this new transportation system.

This link made travel between Dawson and Whitehorse during the ice-free months of the year relatively easy. Travellers to the Klondike could take the 110-mile train ride from Skagway to Whitehorse within a day, and from there a three-day downriver trip on a steamboat would land them at Dawson. South-bound travellers from the Klondike could take a five- to six-day steamboat ride upriver to Whitehorse and then the railway to Skagway, where they could get on a coastal steamship to points south. Whitehorse at this time was primarily a transition point between the steamboats and the railway, with a population in the 1901 census of 800.

This steamboat-railway system that began in 1900 would provide service between the coast and the Klondike for the next 55 years. A significant limitation, however, was that it was a seasonal system. Although the railway could run year-round, the steamboats could only operate reliably for roughly a third of the year. Over the remainder of the year, travel between Dawson and Whitehorse was a very different story.

For three weeks to a month in the late fall when the Yukon River was freezing up and for a similar period in the spring when the ice was breaking up, travel could not be safely undertaken. During these times the Klondike was “cut off from the outside world”, as expressed by author Laura Beatrice Berton when she was a resident of Dawson.

In the months between, when the Yukon River was solidly frozen, the only option for travelling south to the coast was a long and sometimes hazardous trip along a trail on the ice of the river and Lake Laberge. This journey could be difficult because of jumbled ice and deep or drifted snow, and also risky due to thin ice, open leads of water or severe weather. Depending on the snow and weather conditions, the traveller’s health and fitness, and the size of their load and means of hauling it, the trip on the ice trail usually took a couple of weeks and often longer. This trail, at first about 450 miles long, was well-used in both directions by people on foot, skis, dog teams, horse-drawn sleighs, and even bicycles.

may be the start of the trip on which he was murdered on Christmas Day 1899 near Minto.

(Ancestry.ca – Fletcher-Clark Family Tree)

Some of the difficulty and risk of travel on the winter trail was alleviated in 1899 when a 94-mile shortcut was constructed over land from the north end of Lake Laberge to near Yukon Crossing, north of Carmacks. It was built by the Canadian Development Company (CDC), which had the mail contract at the time, and was referred to as the ‘CDC Cut-off’.

This shortcut avoided many miles of travel on the winding Yukon River between Lake Laberge and Carmacks and reduced the Dawson-Whitehorse distance from 450 to 370 miles. It also had the effect of bypassing a number of small communities that consisted of one or more of a North-West Mounted Police post, trading post, telegraph station and First Nation settlement at places such as Lower Laberge, Hootalinqua, Big Salmon and Little Salmon.

In 1899 the Yukon Territorial Government began funding the construction of roads and trails, and over the next couple of years 140 miles of wagon roads and 250 miles of winter sleigh roads and trails were constructed. These were mostly in the Klondike goldfields area, but there were also a few built to serve the developing copper mines near Whitehorse.

Also in 1899, the Yukon Telegraph project had been completed to Dawson, providing residents, businesses and governments of the region with improved communication abilities with the outside world. While this service was welcomed and well used, the movement of mail, goods and people in the winter remained an issue.

By 1901, Dawson residents were agitating for more dependable winter transportation to address this. A newspaper editorial in December of that year said that “Dawson has become a commercial center of big operations and it is absolutely necessary … that constant and uninterrupted communication be maintained with the outside”. It followed with “the natural solution of the matter is the construction of an overland trail” between Dawson and Whitehorse, and “as soon as the steamers cease running in the fall, stages could be placed in operation and continue so until the boats begin plying on the river in the spring”. It was envisioned that this would become the route for all of the winter traffic, and it could also be used in the summer to bring cattle on the hoof to Dawson

Planning the Overland Trail Route, 1901-02

In 1901 government officials in the Yukon were anticipating that funding would be provided for a winter road and started planning for it. In December, Yukon Commissioner James Ross said that “an overland road would … afford uninterrupted communication for Dawson with Whitehorse and through to the coast”. He tasked Territorial Engineer William Thibaudeau with conducting “a preliminary survey with the purpose of reporting on the feasibility and the probable cost of building a trail or road from Dawson to [Fort] Selkirk”, as a start.

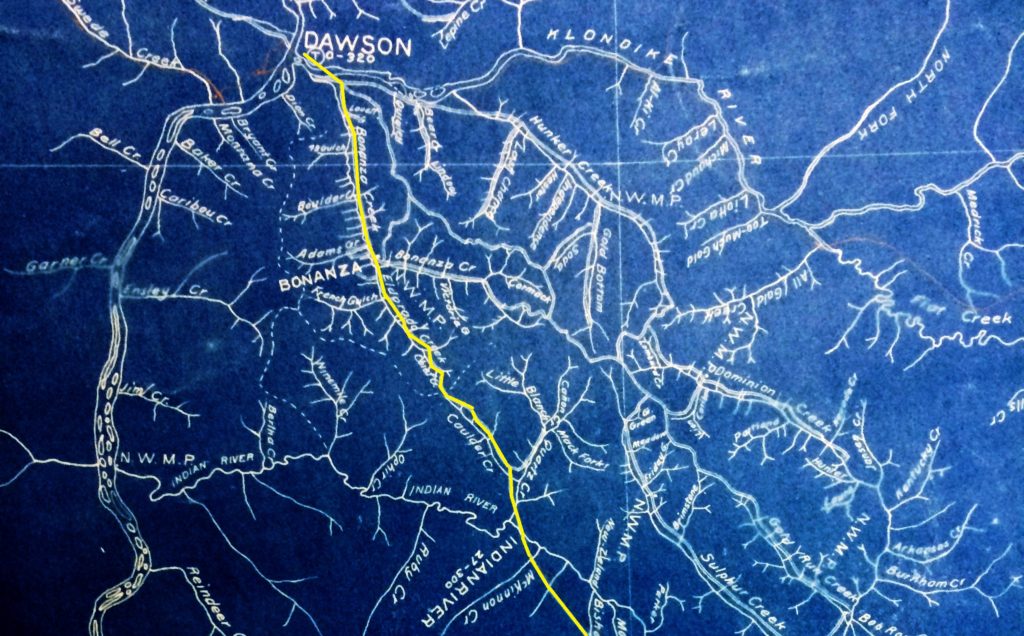

In early May 1902, Thibaudeau laid out a route for the first 50 miles southward from Dawson, using some of the existing mining roads in the goldfields. This route went up Bonanza and Eldorado Creeks, then over the divide into the Indian River drainage, where it crossed Quartz Creek, Indian River and Eureka Creek on the way to Wounded Moose Creek.

(Yukon Archives, Map R-241)

Later that month, Commissioner Ross confirmed that federal funding had been obtained to build the winter road. This launched the Overland Trail project, also known by other names including Dawson-Whitehorse Road and Old Dawson Trail.

Construction of the road would begin in mid-July, but prior to that Thibaudeau needed to determine the whole route so that it could be marked out on the ground for the work crews to follow. It was clear that the road should be in as straight a line as possible between Dawson and Whitehorse “to cut down the distance now required to travel”. This parameter would also open up some new country for potential development, particularly in the Indian River and Stewart River areas.

In 1902 almost all of the developments and activities between Dawson and Whitehorse were situated along the Yukon River, the gold mining creeks, and the trails between them. These consisted of small communities, wood camps, placer mining camps, fish camps, homesteads, roadhouses, telegraph stations, and North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) posts.

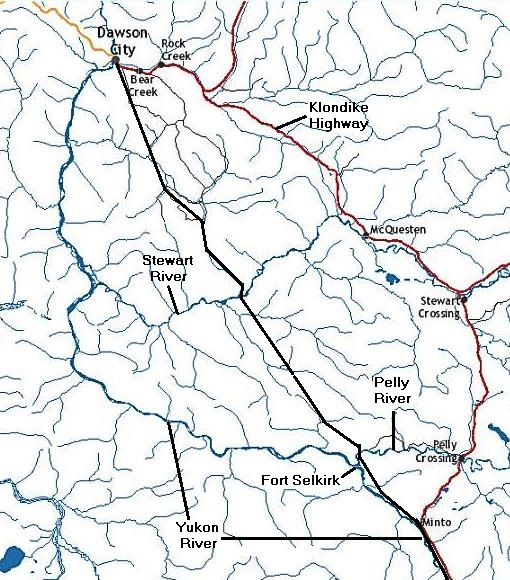

While the original winter trail was along the Yukon River, the Overland Trail was planned to follow the river valley for only about 65 miles, from the mouth of the Pelly River to Carmacks. This meant that the established places between the Pelly River and Dawson such as Fort Selkirk, Selwyn, Thistle Creek and Stewart Island would be bypassed by the winter road.

Thibaudeau was able to plan a relatively straight-line road by following some existing roads and natural routes. These included the route he had already established from Dawson to Wounded Moose Creek, the relatively wide and flat Yukon River valley between Fort Selkirk and Yukon Crossing, and the CDC Cut-off trail between Yukon Crossing and the Montague area, south of Carmacks. Thibaudeau himself would later take charge of locating and blazing most of this portion of the route for the work crews to follow.

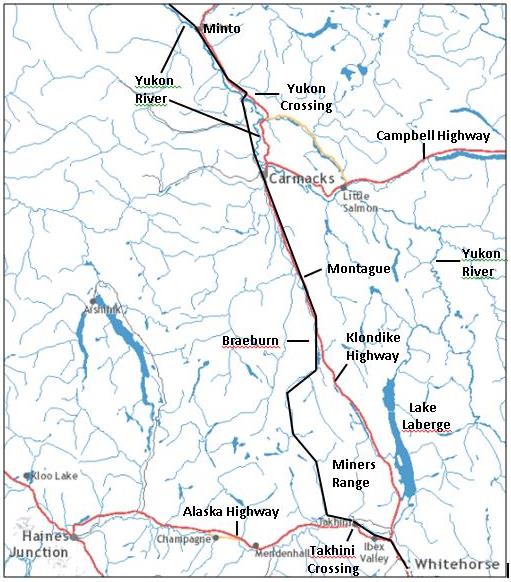

(GeoYukon map base)

From Montague to Whitehorse, the route would deviate to the west of the Miners Range to follow a natural travel corridor along Klusha Creek and Little River that First Nations people had used for eons and that the government had built a winter trail through in 1899. From there it would cross the Takhini River several miles downstream and then go cross-country southeast to Whitehorse. Archibald McPherson, a Dominion Lands Surveyor, was later engaged to supervise the locating and building of this portion of the road.

(GeoYukon map base)

One section of the planned Overland Trail that was neither an existing nor natural route was on each side of the Stewart River. From Wounded Moose Creek, where Thibaudeau had left off in early May, south to the Stewart River and beyond to the Pelly River was country that was not well known. For these areas Thibaudeau may have had advice from people with some knowledge of the geography, but he would still have to scout out and find a roadway through once he was on site.

Locating and Blazing the Overland Trail, 1901-02

With his road plan in place, William Thibaudeau set out in early June with eight men to resume laying out the route southward to get a head start on the road work crews. He and his crew would have had to haul their own camp, provisions and measuring instruments, which had to have been done with the aid of pack horses.

From Wounded Moose Creek, Thibaudeau immediately had to tackle the hilly and relatively remote 25 miles to the Stewart River and then the 56 miles over to the Pelly River. Here his work, referred to as “running the levels”, was to establish acceptable grades along the hills for horse-drawn sleighs and wagons. This was a more important criterion for route selection than issues related to water and wet ground because the road would primarily be used when frozen. The section of Overland Trail from Stewart River to Pelly River will be looked at in more detail in a separate article.

Over the summer Thibaudeau blazed the route southward across the Stewart, Pelly and Yukon Rivers to near Carmacks, where his Overland Trail work finished. He had located and marked out around 160 miles of road for the work crews, about 80 miles of it through fairly rugged and little-known country. From there he went on to locate other roads in the Hootalinqua region before returning to Dawson in early November after five months of work in the bush.

The remaining 125 miles of the road from north of Carmacks to Whitehorse that was in the charge of Archibald McPherson was through comparatively flat country along the valleys of the Nordenskiold River, Klusha Creek (at the time referred to as the east branch of the Nordenskiold), Little River and Takhini River. He had started the work on this section in early August and it was completed by mid-October.

Building the Overland Trail, 1902

In 1902 the Yukon government contracted the White Pass & Yukon Route, which also held the mail service contract, to build the Overland Trail for the price of $129,000 (over $3 million in 2020 dollars). It specified a clearing width of 12 feet with a 6 foot roadbed, expanded to 9 feet on hillsides exposed to snowdrifts, and turnouts (passing places) at convenient spots.

The project was divided into sections based on three of the four major rivers that the road was to cross: Dawson to the Stewart River crossing 45 miles up from its mouth; Stewart River to the Pelly River crossing three miles up from its mouth; Pelly River to Yukon River at Yukon Crossing; and Yukon Crossing to Whitehorse, which included the fourth river crossing at the Takhini River, 19 miles up from its mouth.

(Google Earth)

The road work crews were being organized by early July in Dawson and later in Whitehorse. The Yukon government laid out a policy for the contractor to employ “men who have worked on the creeks as miners and have developed the country” and “who, when they get new grubstakes, likely will again invest their money in the district”. They were paid $5.00 per day with meals supplied and “should come out of the engagement $200 to the good”. The road workers were supported by camps with cooks following along the road in horse-drawn wagons.

Most crews were taken by boat to the river crossings of the Overland Trail, where they were split into two groups, one working each way from the crossing. Territorial Engineer Thibaudeau estimated that “a gang [crew] of 20 men and two teams [of horses] will build on average one mile in two days”. As it turned out, 1902 was a rainy summer, which ended up slowing the work and increasing the cost.

The road construction work was very labor intensive, with clearing of brush and timber done with axes and cross-cut saws. Horse-drawn implements such as scrapers and graders were used for dirt moving, but there was also significant pick and shovel labor to install culverts and bridges as well as to build and crib embankments.

The Geological Survey of Canada geologist Hugh Bostock, who walked many miles on various parts of the Overland Trail over two decades beginning in 1934, remarked that “it is worth remembering that [this road was] built before bulldozers!, by manual labor and horse drawn ploughs and scrapers”. Examples of the manual work are places along the Overland Trail where embankments or retaining walls of rock that were placed by hand can still be seen.

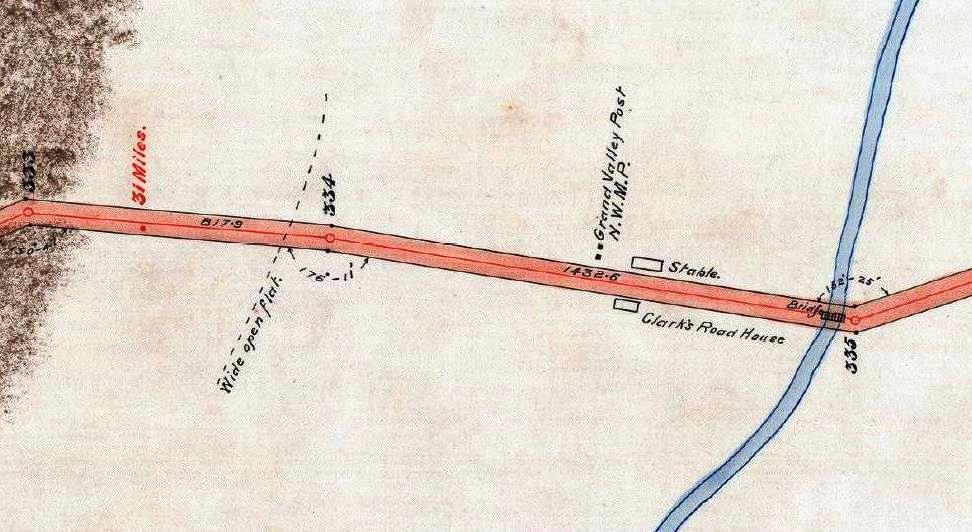

(Gord Allison photo)

Also at the river crossings, rowboats or canoes were kept for travel across the river when the ice was running in the spring and fall and the ferries could not be used. The crossings all had roadhouses on one side, and on the opposite side stables were constructed to keep horses and feed, along with sleighs or wagons, during these periods. This system allowed the people, mail, and limited freight to be transported across the river by boat so that the trip could continue using the horse teams on the opposite side.

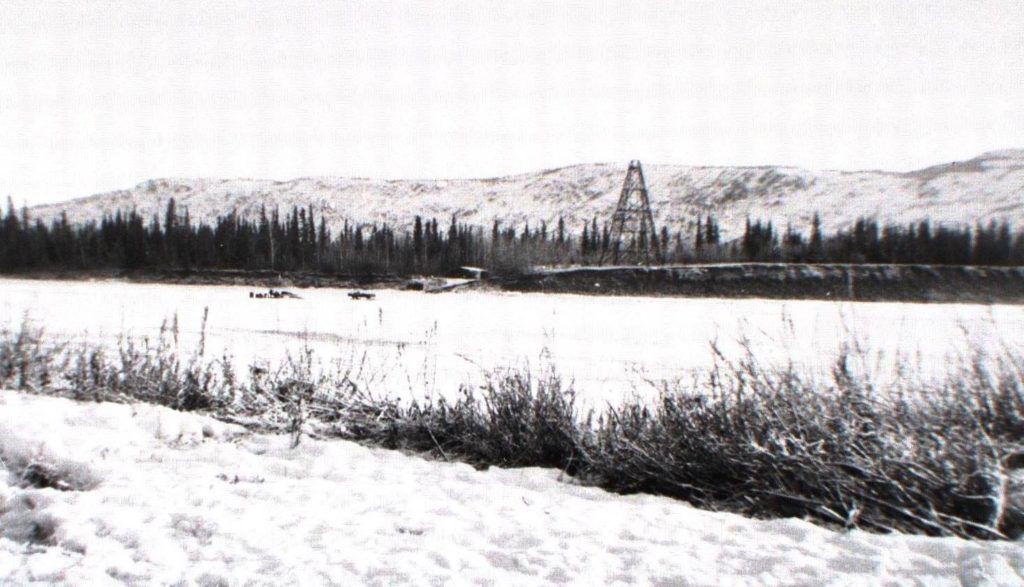

(Yukon Archives, Charles Coghlan Fonds, Acc. 83/19, #128 – photo has been cropped)

At the Stewart, Pelly, Yukon and Takhini river crossings, additional infrastructure was eventually put in place. This consisted of hand-operated cable ferries, powered by the river current, that were used during the spring and fall periods when the road was firm enough for travel but the rivers were ice-free. The ferry cables were strung between towers on each side of the river, described this way by Hugh Bostock: “the high, gaunt, red-painted log towers that held the cables clear of summer steamboat traffic [were] picturesque landmarks”.

(Yukon Archives, Bud and Jeanne (Connolly) Harbottle fonds, Acc. 82/345, #6165 – photo has been cropped)

(Yukon Archives, Robert Ward Fonds, Acc. 77/46, #8864 – photo has been cropped)

The road construction crews finished their work in late September and early October and were returned to where they had been hired, either at Dawson or Whitehorse. The Dawson-Whitehorse Overland Trail was formally opened in late October 1902, and by that time it was well frozen. On October 28 the first traffic on it in the form of horse pack trains left Dawson with provisions for some of the new roadhouses along the road.

The mail service had also geared up to start once the Overland Trail was ready for travel, with light wagons at first used for hauling the mail, along with freight and passengers, until the road had a sufficient snow base to enable the use of sleighs. The trip between Whitehorse and Dawson typically took five days, but at times of extremely cold weather additional days could be spent at a roadhouse until it warmed up. The first White Pass & Yukon Route Royal Mail stage over the new road left Whitehorse on November 2 and arrived in Dawson four days later.

(Yukon Archives, Robert Coutts Fonds, Acc. 86/15, #37 – photo has been cropped)

Territorial Engineer William Thibaudeau, who had put so much work into planning, locating and blazing the Overland Trail had this summation of the project: “[it] has made possible for the first time in the history of the Territory the delivery of mail regularly and has also made it safe for life and property in travelling to the outside”.

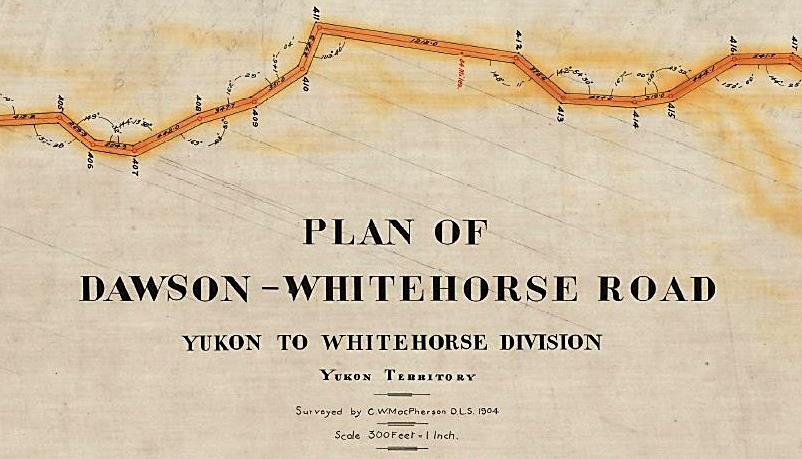

Surveying the Overland Trail, 1903-04

In the summers of 1903 and 1904, three of the four sections of the Overland Trail were legally surveyed by Charles MacPherson, a land surveyor based in Dawson, and his crew. In 1903 the Stewart River to Pelly River and Pelly River to Yukon Crossing sections were surveyed, and in 1904 the section from Yukon Crossing to Whitehorse was surveyed. It appears that the section from Dawson to the Stewart River was not surveyed.

(Canada Lands Survey Records #21988)

The survey crew, which likely consisted of around eight people, carried out its work in the summer on a road designed to be used in the winter when wet ground was not a concern. The crew would have had to haul their camp and provisions as they went, presumably using horses, but the wet places likely prevented the use of wagons. These sorts of details seldom show up in the written records of this type of work, but the travel and logistical challenges associated with it can be imagined.

The survey work defined a 66-foot right-of-way by pairs of wooden posts put into the ground at each corner or bend of the road. The surveyors started with post pair #1 at the northern end of each section and worked their way southward. The 249 miles surveyed from the Stewart River to near Whitehorse required almost 3,600 posts, all or most of which were hand-hewn from trees on site. The posts, squared to four inch sides, were about three feet long with a pointed bottom end for pounding into the ground.

River, 2017. The large tree has grown up in the meantime and is pushing the post to the

right. The road is up the slope to the left of the photo.

(Gord Allison photo)

In addition to the survey posts, mileposts were placed along the Overland Trail and are shown on MacPherson’s survey plans and field books. They are complete with measurements from the survey posts, indicating they were installed in conjunction with the road survey. The mileposts were larger than the survey posts at about five inches squared and closer to five feet long, and had the mile number carved in Roman numerals vertically along the side facing the road.

Similar to the survey posts, the milepost numbering started at 0 at the northern end of each Overland Trail section. On the survey plans, the mileposts appear to have been placed closer to the road than the survey posts to be readily visible to travellers, particularly the stage drivers, although any reference to a certain milepost would also have had to specify the section it was in.

MacPherson and his crew also surveyed land parcels along the way, including four North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) reserves and three roadhouse lots. His survey plans and field books noted the locations of the NWMP and roadhouse buildings, along with bridges that had been constructed at creek and small river crossings.

(Canada Lands Survey Records #10673)

Roadhouses on the Overland Trail, 1902-1930s

Some sections of the Overland Trail were already served by existing roadhouses, including ones in the Klondike goldfields, along the Yukon River at Minto, Yukon Crossing and Carmacks, and one on the winter CDC Cut-off trail at Montague. However, many more in other sections needed to be built to provide shelter and services to travellers, and some to serve as mail stations.

These new roadhouses came on the heels of the Overland Trail construction in the fall of 1902. William Thibaudeau, on his way home to Dawson in November after completing his field work on the road, noted the construction of roadhouses along the route, including some that were already in operation. He commented that “the roadhouses every twenty miles are very different to the old ones [on the river trail]. They are mostly 40 by 25 feet, of two stories, well furnished, well heated and lighted, and you can get just as good a meal as in any place in town”.

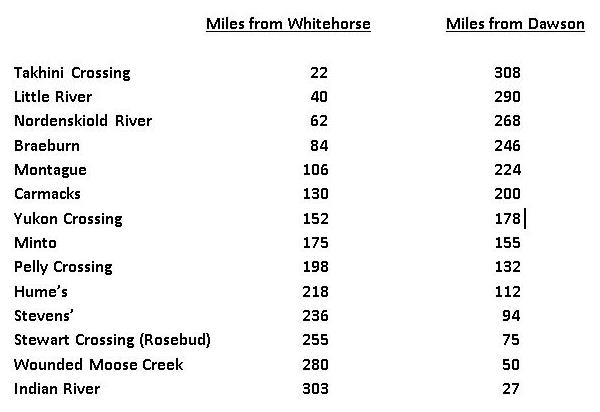

White Pass, which held the mail contract and also operated a freight and passenger service, was the primary user of the road and established 14 roadhouse/mail station stops between Whitehorse and Dawson, an average of 22 miles apart. These are, from south to north (distances vary by up to four miles depending on the source, but those given below were taken from the survey plans):

The roadhouses were under a variety of ownership and service arrangements, with some owned by White Pass and operated by employees or leased to operators, and some that were privately owned with a service contract to the company. Many of the roadhouse operators were ‘reverse snowbirds’, working in the Yukon on the winter road and then going ‘outside’ for the summer.

Many of the White Pass steamboat captains were true snowbirds, going ‘outside’ for the winter, which meant that the company risked losing the captains’ valuable river experience and expertise if they found employment elsewhere. As an incentive for them to stay the winter rather than leave and possibly not return, the company entered into roadhouse operating arrangements with some of them. The details of this are not known, but at least three captains ran roadhouses under this arrangement: William Turnbull at Yukon Crossing, John Fussell at Minto, and Thomas Whelan at Pelly Crossing. Two of them, Fussell and Whelan, even purchased the parcels of land that their roadhouses sat on.

The geologist Hugh Bostock visited many Overland Trail roadhouse sites in the 1930s and ‘40s in the course of his work and described them as “… a complete establishment, with roadhouse, stables, storehouses, and cabins … The roadhouses themselves were large two-storey log buildings with gently sloping gable roofs, dirt-covered to keep out the cold, and sheeted with boards to shed the summer thunder showers”. He also said that “they usually faced the road and their large, low, flat-roofed log stables stood opposite. Several storehouses and cabins were clustered around, each flanked by wood piles…”.

Roadhouses on the Overland Trail were all fairly similar, since they had to adhere to government-specified standards. This was particularly the case when they had a liquor licence, which most did. Bostock also described the function and importance of roadhouses: “here board and lodging as well as fresh teams of horses and drivers were provided for the travellers and the mail stages. The [roadhouses] contained all the necessities of life and the comforts of those days for winter travel and were a welcome and vital refuge for man and beast from the intense cold”.

(Canada Department of Mines, Geological Survey Branch, Memoir #5, “Lewes and Nordenskiold Rivers Coal District, Yukon Territory”, by D.D. Cairnes, 1910)

Before the rivers froze in the fall, provisions for the winter were delivered by steamboat to the roadhouses that were situated along the rivers. Those roadhouses that were in the interior, away from the rivers, had their goods stockpiled on the riverbanks at the crossings until the road was sufficiently frozen for them to be hauled by wagon or sleigh teams.

Many roadhouses were known as well or better by the names of the operators, who became fairly well-known themselves, rather than by their physical locations. For examples, the Takhini Crossing roadhouse was called ‘Puckett’s’ while William Puckett operated it and the Pelly Crossing roadhouse started out being called ‘Whelan’s’ for Thomas Whelan and later as ‘Mrs. Schaeffer’s’ when Margarete and her husband Alex Schaeffer (also called Shaver) took it over.

Details and insights into the operation of Overland Trail roadhouses and the winter stage line can be found in Laura Beatrice Berton’s book I Married the Klondike and a Yukon Government booklet called “The Overland Trail”. The latter is available at https://yukon.ca/en/overland-trail

In addition to the 14 White Pass roadhouse and mail stations, there were at least 12 others established that appear to have been private entrepreneurial endeavors. They were presumably aimed at garnering business from other travellers, including passengers of a few independent stage lines. These roadhouses also may have provided emergency or warm-up services to White Pass passengers due to breakdowns or cold weather. Most of these independent roadhouse efforts were relatively short-lived, lasting only a few years after the Overland Trail was built.

Roadhouses along the Overland Trail ceased operating when the portion of the road they were located on was abandoned as a travel route. The longest lasting ones were along the last part of the Overland Trail to be abandoned, between Whitehorse and Minto. There seems to be little information on the dates of closure, but it appears from newspaper articles that many kept going into the late 1920s at least. The Minto roadhouse was still operating in the winter of 1936-37 when Ione Christensen stayed there as a young girl with her mother. Her main memory is of her enjoyment watching pack rats (presumably bushy-tailed woodrats) that were in the roadhouse, but her mother was not as impressed.

North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) Posts on the Overland Trail, 1902-1950

The North-West Mounted Police and its successors, the Royal North-West Mounted Police and Royal Canadian Mounted Police, always had to adapt their distribution of posts (detachments) to changing developments. The first post, Fort Constantine, was established in 1895 at Forty Mile, down the Yukon River (north) from Dawson, due to the increasing numbers of miners in the area. After the discovery of gold in the Klondike the following year, many more posts were built and later abandoned as circumstances warranted.

In 1902, when winter travel between Whitehorse and Dawson was about to shift from the Yukon River winter trail to the new Overland Trail, the NWMP had to undergo another change to its distribution of posts. NWMP Assistant Commissioner Zachary Wood, Commanding Officer in the Yukon, stated that “the new winter trail to White Horse, just completed, will necessitate the establishment of new detachments as, with three exceptions, it does not pass anywhere near any of our summer outposts on the river”.

Six new posts were built along the Overland Trail, all at locations where roadhouses were also being established. These and the existing posts, for the first three years at least, were as follows, from south to north:

Posts along the Yukon River and Lake Laberge that were bypassed by the Overland Trail were closed, at least seasonally. The members were often shifted from summer posts on the river to winter posts along the road when the steamboats ceased running in the fall, and vice-versa in the early summer when the boats resumed operations. The few posts that were on both the Yukon River and the Overland Trail, at Carmacks, Yukon Crossing, Minto and Fort Selkirk, continued to be staffed year round. Fort Selkirk was technically not on the Trail by a few miles, but a connector road was built to it.

(Glenbow Archives, #PB-121-2)

After all the efforts of establishing and relocating police posts as conditions required during and following the Klondike Gold Rush, the Yukon saw a major reduction in staff in 1905 and again in 1906. Most posts along the Overland Trail were closed, with only the ones needed to provide service on a year-round basis retained. Aside from Dawson and Whitehorse, which had been in existence continually since 1896 and 1900, respectively, only the Carmacks and Fort Selkirk posts continued to provide service on the Overland Trail.

Re-routing and Abandonment of the Overland Trail

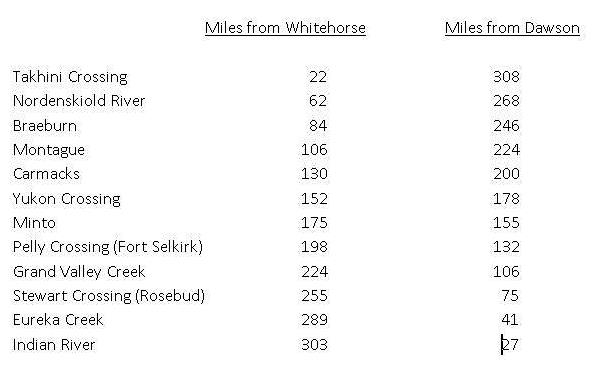

Over the years there were significant changes to the Overland Trail. One of them was a diversion to alleviate difficulties with the original route in the Minto area. The other two were new roads built in response to resource developments and resulted in abandonment of portions of the original Overland Trail route.

The diversion started at Minto, where just downriver (northwest) from it the road began to wind its way for about five miles along hillsides on the edge of the Yukon River, including a stretch known as the Minto Bluffs. Parts of the road were dug into the hillside, in places supported with hand-placed rock embankments. As early as the summer of 1903, the year after construction of the road, it was reported that parts of it that were close to the river were subject to damage from high water and ice jams.. Also, some of the slopes were relatively steep and the roadway cut into them was prone to slides and sluffing.

(Gord Allison photo)

A Minto area farmer named Harris Welch scouted out an 18-mile road on the opposite (east) side of the hills that would alleviate this issue. He brought it to the attention of the government, and while it is not known what response he received, at some point a new 22.5-mile road was built from Minto to near the mouth of the Pelly River along the route Welch had suggested.

(Yukon Archives, GOV 1630, File 4738)

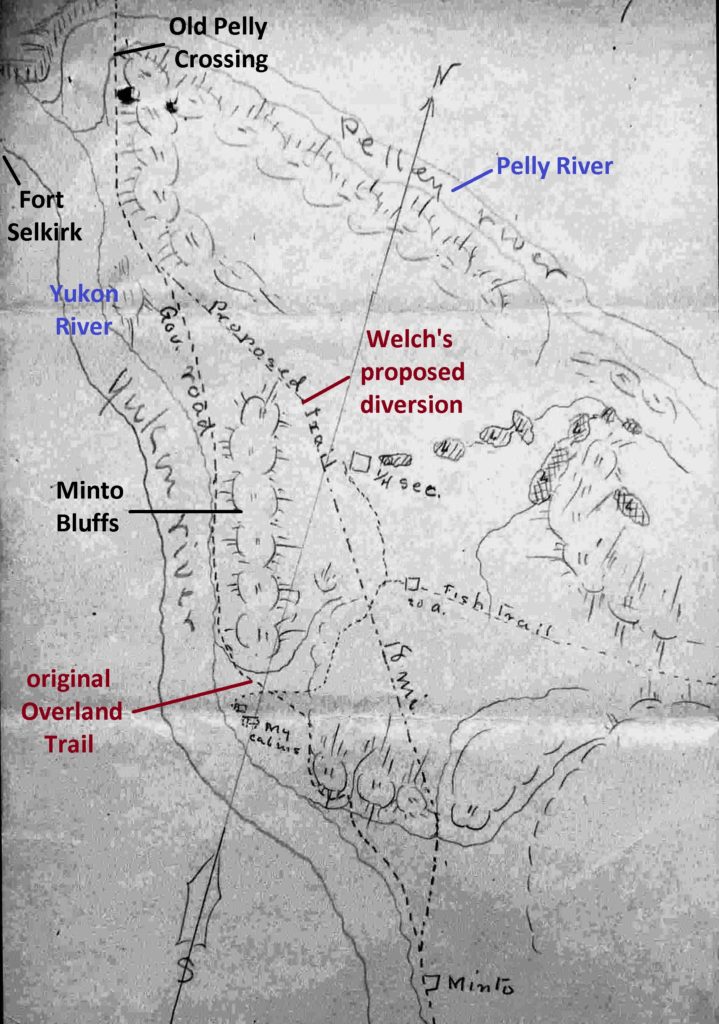

In the Stewart River to Pelly River section of the Overland Trail, the original route was used until 1912, when a significant change was made. Following gold discoveries in the Scroggie Creek area to the west, a new road about 55 miles long was built from a point on the Overland Trail 11 miles north of the Pelly River. It went northwest into the Scroggie Creek drainage and to the mouth of the creek at the Stewart River. From there the road was extended onto the north side of the river, including a ferry at the crossing, and went via Black Hills Creek into the Klondike goldfields, rejoining the original route near Eureka Creek.

Known as the Scroggie Road, this new route was longer than the original one, but it was built on drier slopes with good grades and proved to be a better road. It spelled the abandonment of the northerly 45 miles of the original Overland Trail between the Stewart and Pelly Rivers, and the roadhouses as well. Four new roadhouses were established along the Scroggie route at Black Creek (called Wheeler’s roadhouse), Alberta Creek, Scroggie Creek (at the mouth), and Black Hills Creek.

In the early 1920s a major deviation from the Overland Trail was made in response to the increased silver mining activity in the Mayo area, which was soon to exceed Klondike gold production in value. A new road was built from the Overland Trail at Minto to present-day Pelly Crossing and beyond to near present-day Stewart Crossing, where roads then branched northeast to Mayo and northwest to Dawson. These soon became the main roads, bringing about the general abandonment of all of the original Overland Trail north of Minto as well as the Scroggie Road.

(from Gordon Bennett, Yukon Transportation: A History, p. 87)

By 1921 the population of the Yukon had dwindled to 4,157, with 975 in Dawson (plus more on the gold creeks) and 331 in Whitehorse. White Pass relinquished the winter mail service contract because the low volume of mail, freight and passengers made it unprofitable. The company had made its final winter mail stage run in the spring of 1920 and terminated its Overland Trail operations. This signalled the beginning of the end of winter transport with horses, and the mail and freight soon began to be hauled by smaller contractors using mechanized means such as ‘cat trains’, half-track vehicles, and trucks.

The condition of the Overland Trail gradually deteriorated and by the late 1930s, with the beginning of mail service by airplane, the few travellers and little freight could not sustain a transportation company. The Overland Trail was pretty well abandoned as a commercial route at this time.

In 1942, the construction of the Alaska Highway northwest from Whitehorse more or less followed the Overland Trail for the first 32 miles, using the same ferry crossing of the Takhini River. Near the Little River, the highway branched west onto the Kluane Wagon Road and followed the route of that road westward. The Overland Trail heading north from that point is still the original and mostly intact route to a point where it is overtaken by the Klondike Highway about four miles north of Braeburn.

The completion in 1950 of what is now the Klondike Highway between Whitehorse and Carmacks meant that the Overland Trail route west of the Miners Range between Braeburn and Whitehorse became the last original section to be abandoned. By the mid-1950s the present all-weather road system between Whitehorse, Dawson and Mayo was established. This led to the final end of the Overland Trail, as well as to the demise of the steamboats for transportation in the Yukon.

Of the 330 miles of the original Overland Trail route, only about 85 miles are followed by the present highways. The parts of the route that the modern roads use are in the Braeburn-to-Carmacks, Yukon Crossing-to-Minto, and Whitehorse-to-Takhini Crossing areas.

The Overland Trail Now

Some sections of the Overland Trail that were not overtaken by the modern highways are still used for various activities, while other parts are abandoned and becoming overgrown. There are sections used for mining and other resource access, such as in the Klondike goldfields, part of what is now the Freegold Road north of Carmacks, and part of the access to the Division Mountain coal area near Braeburn.

A number of sections are used for one or more of trapping, subsistence and recreational activities, some seasonally and others year-round. Sections used by the Yukon Quest include Takhini River to Braeburn and the first eleven miles of the Pelly River to Stewart River section. Beyond that point the Quest uses the Scroggie Creek route to the Stewart River and beyond.

(Phil Bastien photo)

From Braeburn to the old crossing of the Pelly River near Fort Selkirk, sections of the Overland Trail are still accessible from the roads or river, although parts were used by the North Klondike Highway and Freegold Road. Many of those sections that were not covered by the modern roads are becoming overgrown and can even be difficult to find, particularly where burned over by forest fires.

(Gord Allison photo)

The most pristine parts of the Overland Trail are the 45-mile section of the Overland Trail between the Stewart and Pelly Rivers (north of the fork to Scroggie Creek) and about a 25-mile section north of the Stewart River to Wounded Moose Creek. These parts have been left relatively undisturbed and intact since they were abandoned in 1912.

As for the roadhouses, most of those that were not destroyed by forest fires, washed away with eroding riverbanks or removed for materials or firewood are marked by ruins or remnants and are gradually being reclaimed by the forest. This was happening as far back as 70 years ago, when Hugh Bostock noted that “with roofs fallen and those walls that still stand tilted by the frost, the forest creeps back upon them”. The exceptions are at Montague and Carmacks, where the roadhouses have been rehabilitated and, together with interpretive signage, still stand to show and explain their place and that of the Overland Trail in Yukon history.

(Gord Allison photo)

(Gord Allison photo)

The NWMP/RNWMP posts that were abandoned even earlier than the roadhouses also disappeared many years ago. While some vacated buildings were left in place to be used for patrols, the force tended not to leave its buildings on site after abandonment, unless natural forces were going to take them, and usually moved them to a new or existing site. Only a hole in the ground that was the cellar and perhaps the remains of a small outbuilding or two are often all that mark the sites of these old posts.

The Overland Trail played a vital role in the Yukon’s transportation history and has an abundance of interesting stories attached to it. Some sections of it showed the way for later roads to follow, and others remain on the landscape as evidence of the developments and activities that once occurred there.

Link to related article: The Overland Trail: Stewart River to Pelly River

Updated February 5, 2021