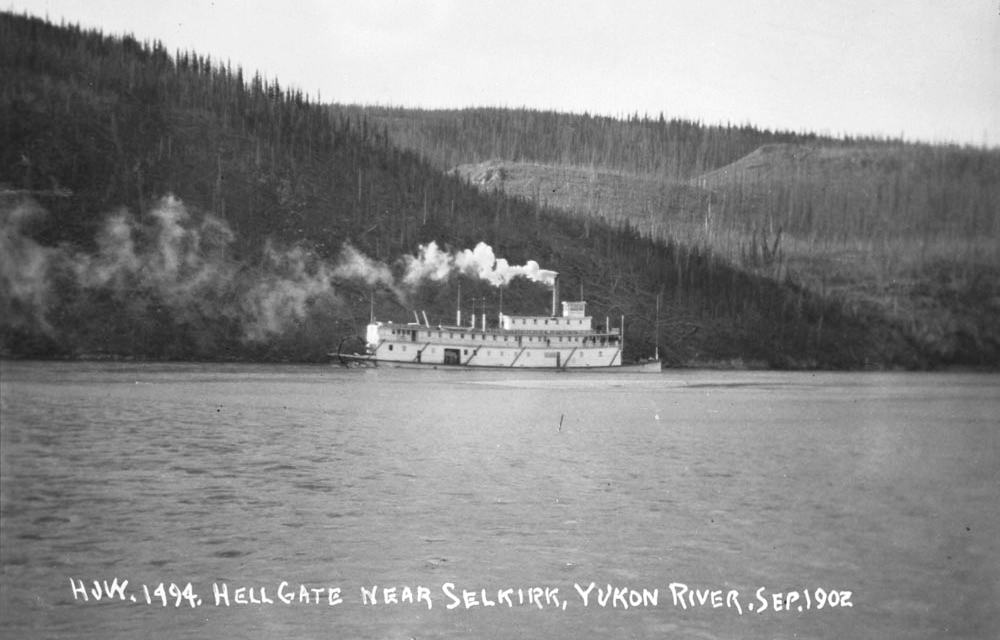

Hell’s Gate (Ingersoll Islands)

(H.J. Woodside, Library & Archives Canada, PA-016495)

During the riverboat era of the Klondike Gold Rush and years following, an area of islands in the Yukon River between Minto and Fort Selkirk was, according to one newspaper, “the worst part of the Yukon River in its entire course from the standpoint of navigation”. This group of islands stretches for almost six kilometers along a widening of the river, which in this area flows in a southeast to northwest direction. These are the Ingersoll Islands, named by American Army Lieutenant Frederick Schwatka, as were many other geographic features, on his expedition through the region in 1883. The name was for Colonel Robert Ingersoll, an American Civil War veteran, lawyer, and political and anti-religion orator.

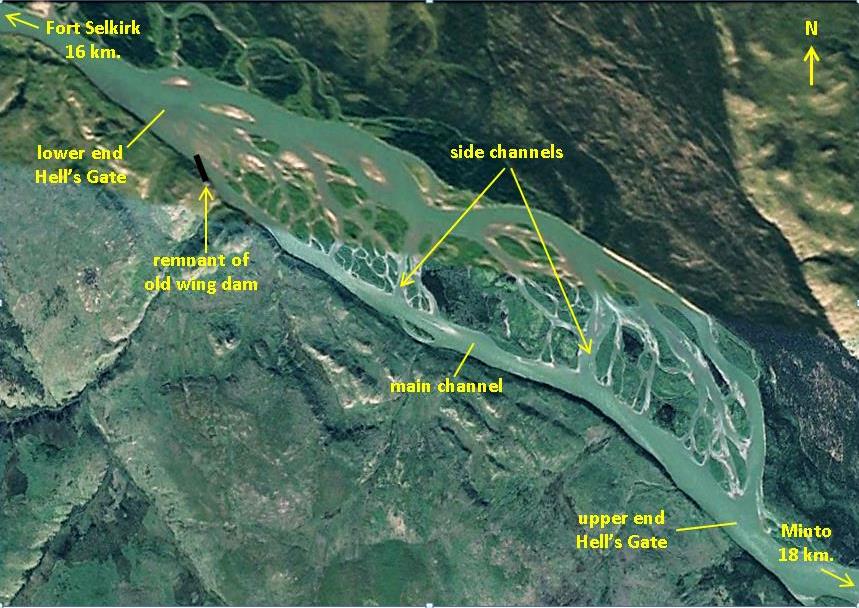

(Google Earth)

As soon as riverboats began operating on this section of the Yukon River, the Ingersoll Islands area became known as an obstacle to navigation. Very quickly it was given the name Hell Gate, or Hell’s Gate as it’s more commonly called today, with the name applied to the whole six-kilometer length of the islands. An old Yukon River channel chart for riverboats has labels for ‘Upper End Hell Gate’ and ‘Lower End Hell Gate’ at the upstream and downstream ends of the island group. These names also appear in reports about projects undertaken to improve the main channel for navigation. Today Hell’s Gate is generally identified, in Yukon River guidebooks at least, as only the location at the lower end of the islands.

(Gord Allison photo)

At the upper end of Hell’s Gate, the river divides into two channels, enclosing the islands between them. The main channel for navigation is along the left limit, which in river terminology means on the left side heading downstream, in this case toward Dawson. As the water flows along this main left channel, much of it is progressively captured by numerous small side channels between the islands and diverted over to the right channel. By the time the downstream end of the islands is reached at lower Hell’s Gate, the amount of water that has been lost from the main channel can make it shallow enough to create difficulties for passage.

Sometimes several riverboats could be held up at Hell’s Gate because one or more of them were stuck and blocking the way of the others. A newspaper article in January 1901 reported that “at one time last fall five steamers were tied up at Hell Gate for three days, greatly interfering with navigation”. One of them, the Eldorado King, was unable to be freed and spent the winter frozen in the ice.

(Yukon Archives, Robert Ward fonds)

River channel improvement work at Hell’s Gate was initiated at least as early as 1900 and went on periodically for years. It was carried out at times by Yukon Government forces and sometimes by the riverboat operators, such as the White Pass & Yukon Route, often with government funding. The work in the early days consisted primarily of two tactics: construction of wing dams built at an angle off of the riverbank to direct water flow into the main channel and to flush out accumulated gravel on the river bottom; and damming off the small side channels between the islands to stop the diversion of water from the main left channel over to the right channel.

(Google Earth)

Both procedures involved installation of log pilings made from nearby timber and placement of tons of rock and gravel that was hauled on barges pushed by riverboats, sometimes from a considerable distance. This material was used to build the wing dams and the side channel dams, and on one occasion a damaged barge was used to plug off one of the channels. Dams totaling hundreds of meters in length were constructed to try to keep the water in the main channel. This work was effective for a handful of years, but eventually the river cut through the finer materials that the islands are made of and around the ends of the dams, requiring them to be added onto or rebuilt.

I have come across little information about how the channel improvement work was actually carried out. Details about how the piles were set in place and driven, how the rock and gravel was quarried, loaded and placed to form the dams, and how the work boats and barges were used in these efforts would be interesting to know. One helpful piece of information is a sketch at the Yukon Archives that shows work done at Hell’s Gate in 1908 to 1910.

(Yukon Archives, Map #1042)

(Yukon Archives, Map #1042)

The only apparent visible remnant today of the impressive amount of channel improvement work is a small section of the wing dam (also referred to as a jetty) protruding from the left limit of the main river channel near the lower end of Hell’s Gate. Anchored into a nearby rock face just upstream is a metal mooring ring for tying a riverboat to.

(Gord Allison photo)

(Gord Allison photo)

Old Government House

The old Yukon riverboat channel chart for the Hell’s Gate area contains a curious notation. A location labelled ‘Old Gov’t House’ shows a building or perhaps two adjacent buildings on one of the Ingersoll Islands. The existence in this area of an apparent government-related establishment with a seemingly elegant name was surprising and intriguing, and it initiated an archival and physical search for the building and its purpose.

The channel chart showed ‘Old Gov’t House’ to be on the southwest side of a large island. A good locational clue was that it was noted as directly across the main channel from Mildred Island, the only island on the left side of the main channel of the river along its course through the Ingersoll Islands.

(Library of Congress)

In August 2017 Ron Chambers and I went to the area to see if we could find evidence of a building on the large island opposite Mildred Island. With some deft maneuvering in the swift, shallow water of a side channel, Ron landed the boat on the island near the location of Old Gov’t House indicated on the old channel chart.

As on many of the Yukon River islands that we have been on, the undergrowth was thick with alders, willows, rose bushes, high-bush cranberries and deadfall, making both walking and visibility difficult. However, we shortly came into a semi-cleared area where sawn chunks of logs showed that some human activities had occurred there many years ago. While this spot didn’t reveal much of interest, a dark shape in the adjacent thicker brush caught our attention. It was only a short distance away, but it would have been very easy to miss.

(Gord Allison photo)

The dark shape turned out to be an unusually large log building with the walls mostly intact, but the roof was collapsed and a section of one wall had been cut out and removed at one time, presumably for firewood. The dimensions were measured by pacing, which was difficult to do in the overgrowth of brush, but it was approximated at 50-60 feet long by 24 feet wide, with a 20 x 20 foot addition or porch on the front side. Large metal pins and hand-made wooden dowels that held the logs together were evident in various places. Little could be seen of the interior because of the collapsed roof and the trees now growing up in it. The thick brush around and within the building also made it difficult to take good photographs for documentation purposes.

(Gord Allison photo)

(Gord Allison photo)

Archival and other research showed that In the summer and fall of 1902 a channel improvement project at Hell’s Gate was undertaken by a crew of fourteen men under the direction of Paul Mercier, Resident Engineer for the Yukon Government’s Public Works. The Northwest Mounted Police report for that year stated that “hardly a boat during the latter part of the season has been able to negotiate [Hell Gate] without running aground”.

Included in Mercier’s project was the construction of a building, variously referred to in a Yukon Archives file on this project as a shack, a house, and a cabin, on the largest of the Ingersoll Islands. The purpose of the building was not specifically stated. The file said that all the timber for the project, including logs for the building, pilings, and bracing for the pilings was cut from this large island.

The file also describes a dispute about what timber berth the logs for the project were cut from, and therefore to whom payment was due. Because of this dispute, the amounts of timber taken are outlined, including 1,892 lineal feet of logs used for the construction of a house. A breakdown of the numbers and lengths of the house logs shows that eight logs of 52 feet in length were used, in addition to 62 other logs of 26 and 22 feet long. The 52-foot logs are relatively long to be used in a building in the Yukon bush and appear to have been used for a long wall with no doors or windows. House logs of this length also indicate that there must have been very good timber on that island.

The location of this building leaves little doubt it is the Old Gov’t House that is noted and mapped on the old riverboat channel chart. The Yukon Archives channel improvement file showing that a building was constructed on the same island in 1902 by a government crew indicates it must almost certainly be Old Gov’t House.

The purpose of the building was the one question left to be determined. Its size and location suggested it may have been a bunkhouse built for the fourteen-man crew working on the Hell’s Gate channel improvements in 1902. This supposition was confirmed by a newspaper article in October 1902, in which the Government engineer Mercier was questioned about the expense of a building for his channel improvement project. He responded that “when men work ten hours a day in water up to their waist, they must be warmly housed and well fed or they cannot stand the work”.

Nobody I have talked to so far with knowledge of this area of the Yukon River knew about this building. Perhaps this is because it was only used during occasional short periods for the sole purpose of channel improvement work at Hell’s Gate a century ago and more. This may not have given it enough profile to stay in the minds and memories of local people as time went on, especially once it was overtaken by vegetation and obscured from view.

Old Gov’t House was presumably constructed on the largest Ingersoll Island because it was central to the crew’s work sites, had a good supply of timber and, as time has shown, was an island of relative stability. The building has stood for 117 years through the forces of ice jams, high water, and shifting channels and islands. Diverse sources of information, combined with finding it on the land, came together to tell the story of this large log building hidden in the Yukon bush.