Moose Jackson (Jänachälatà) was an elder of the Champagne & Aishihik First Nations (CAFN) who passed away in 2011 at the age of 85 or 86. I had always known of him as I was growing up, but not real well until a job at CAFN gave me that opportunity. This turned out to be an unexpected highlight during my time there, becoming a recipient of his perspectives, observations and sense of humor. He willingly shared his knowledge of his land and people, much of this during coffee breaks at my office and some of it on the land.

(photo courtesy of Champagne & Aishihik First Nations)

Moose’s Life

Moose was born on January 2, 1926 (although he told me it might have been 1925) at the village of Hutchi, located on the largest Hutchi Lake about 40 kilometers north of Champagne. He grew up there speaking Southern Tutchone and hunting, fishing and trapping with his family over a wide area of the CAFN traditional territory. He never went to school and said he didn’t learn to read and write, but he must have understated this because he also said that he could follow along in the Bible to taped stories.

Moose said the First Nations people had many trails, and the ones to Hutchi were like spokes on a wheel. The village was a central location for people from many places to get together, and Moose remembered many good times there. He also said the Hutchi area had plenty of fish and game, and that you could never go hungry there.

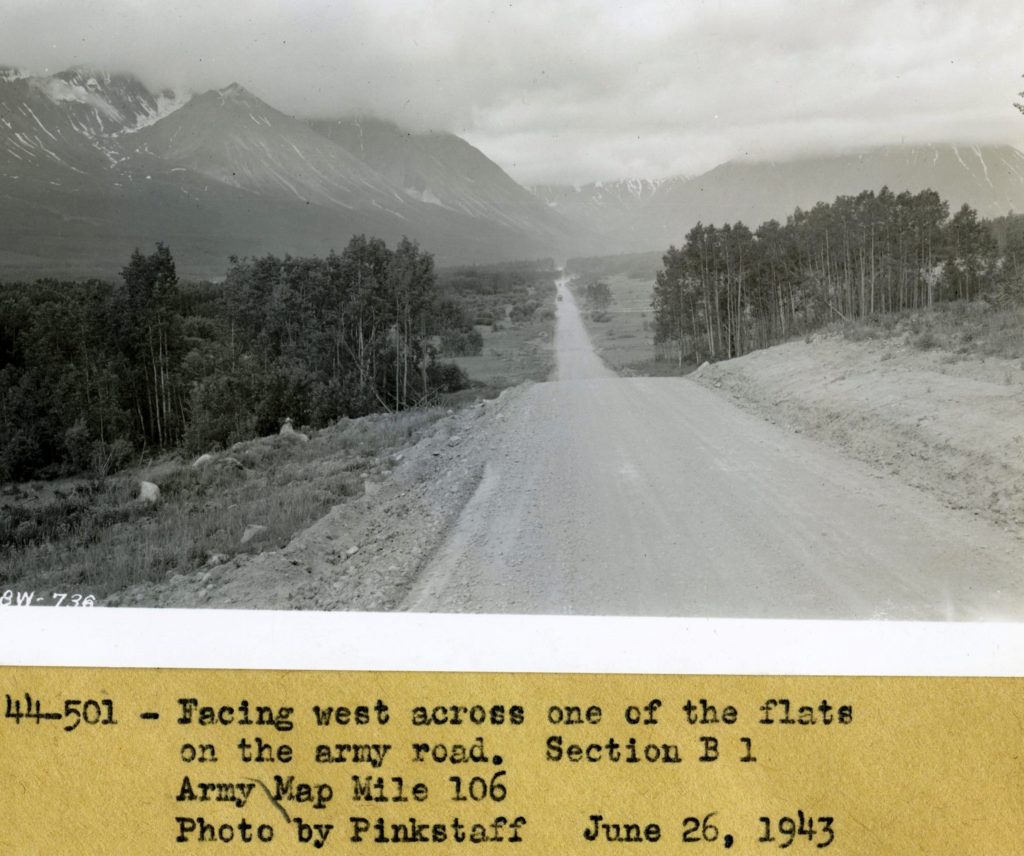

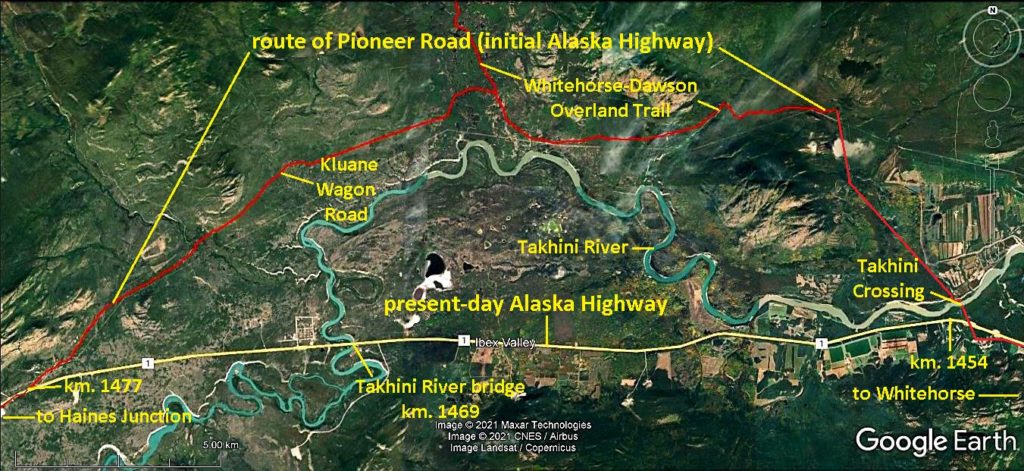

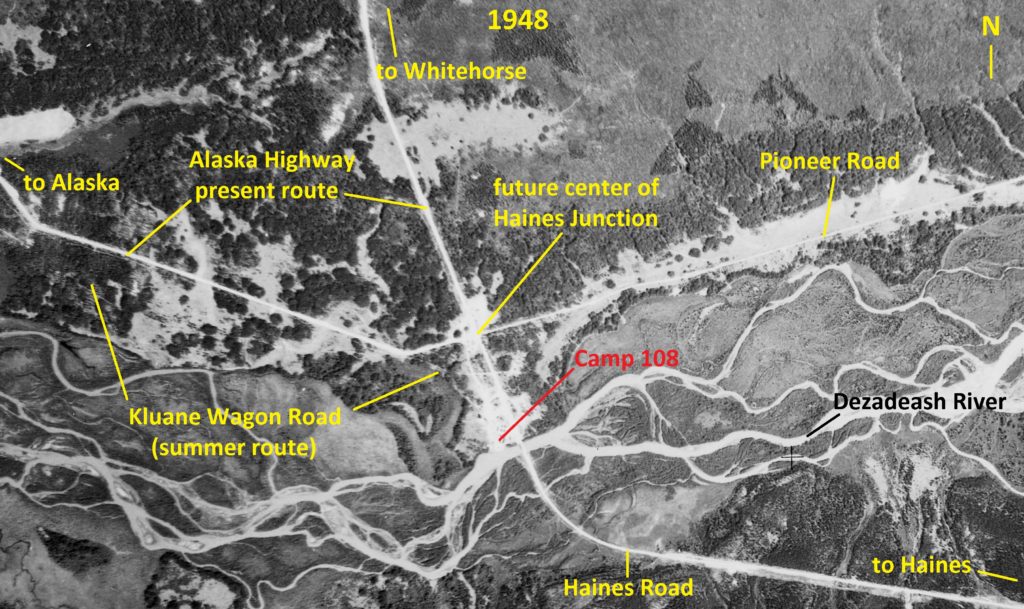

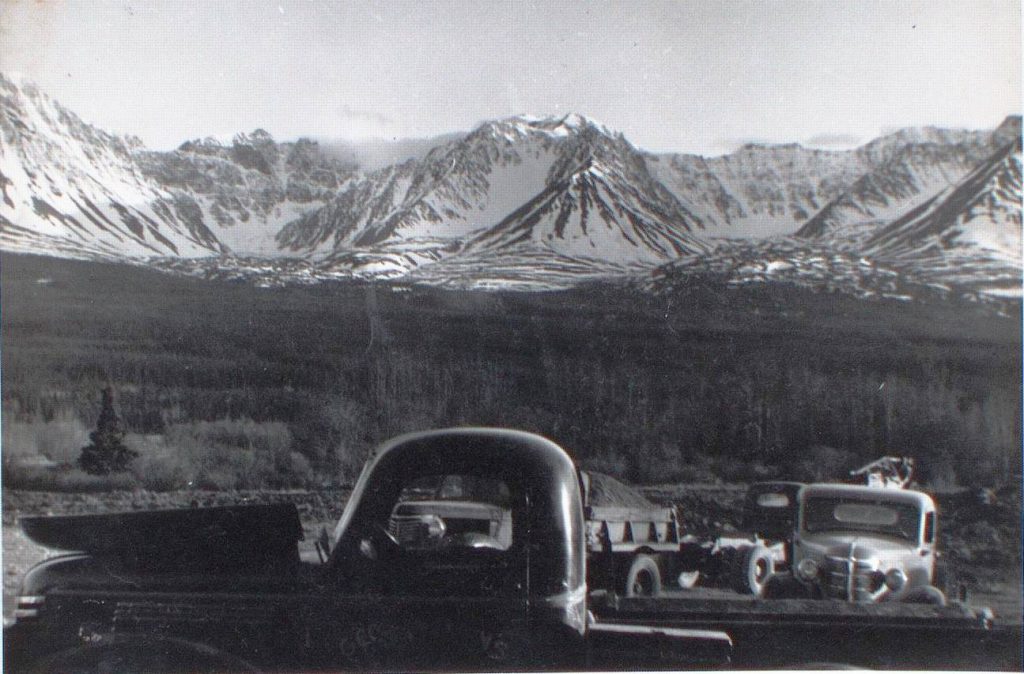

A couple of trails from Hutchi linked to one that ran east-west along the Takhini and Dezadeash River valleys and on to other parts of the CAFN traditional territory. This trail was used as a route for the Kluane Wagon Road, built a couple of decades before Moose was born, to provide access from Whitehorse to new gold discoveries in the Kluane region. Moose said that the wagon road was just a bigger trail for the First Nations people to use. He also said that when much of this same route was used for the Alaska Highway in 1942, it was handy because it was easy to catch a ride on an army truck.

Moose talked about travelling with his parents, Hutchi Jackson and Lilly Isaac, south to Klukshu in the summer to fish and dry salmon to take back home or to caches. He said the trail between Hutchi and Klukshu when he was young was like the Alaska Highway is to us now. In one conversation we had, he made the observation that travel during his early life was mostly oriented north-south, but after the Alaska Highway came through in 1942 the orientation gradually changed to east-west along the Haines Junction – Whitehorse corridor.

Moose had a lot of good memories and admiration of his Dad, who was probably born around 1880 and would have been a young man when outside people first started coming in to his country in the 1890s. Moose said his Dad travelled all over the country, preferring to hunt with his bow and arrows because he didn’t trust rifles. He was a very good cabin builder and built cabins at a number of places throughout the traditional territory.

Moose said his Dad was always healthy, never sick, and even when he was old, he could run down a moose on snowshoes. One day in 1945, when Moose was about 20, his Dad started feeling unwell and went to Champagne because it was ‘time to go’, and died the next day.

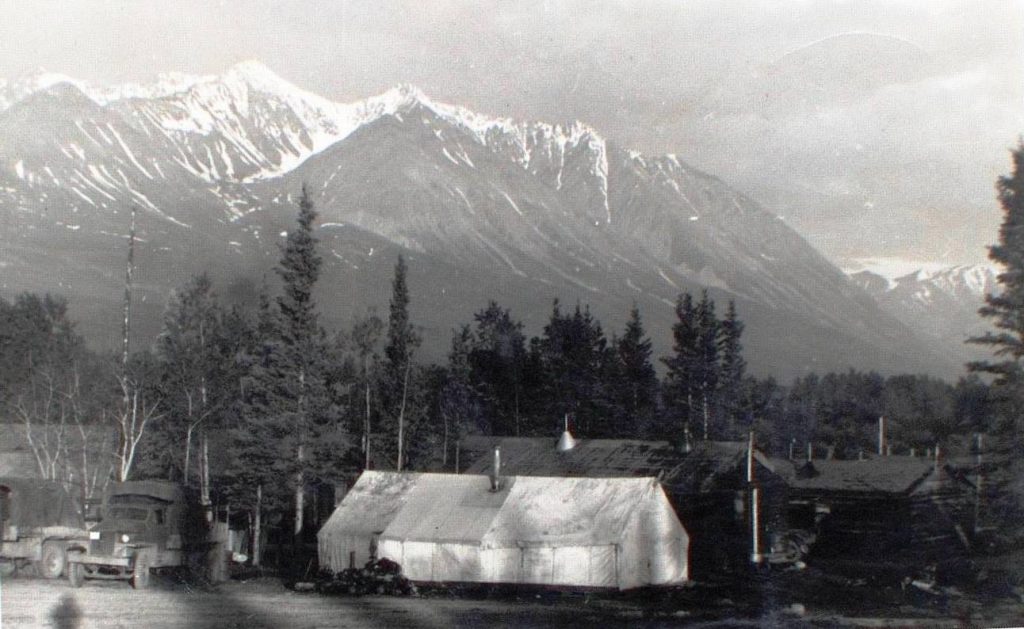

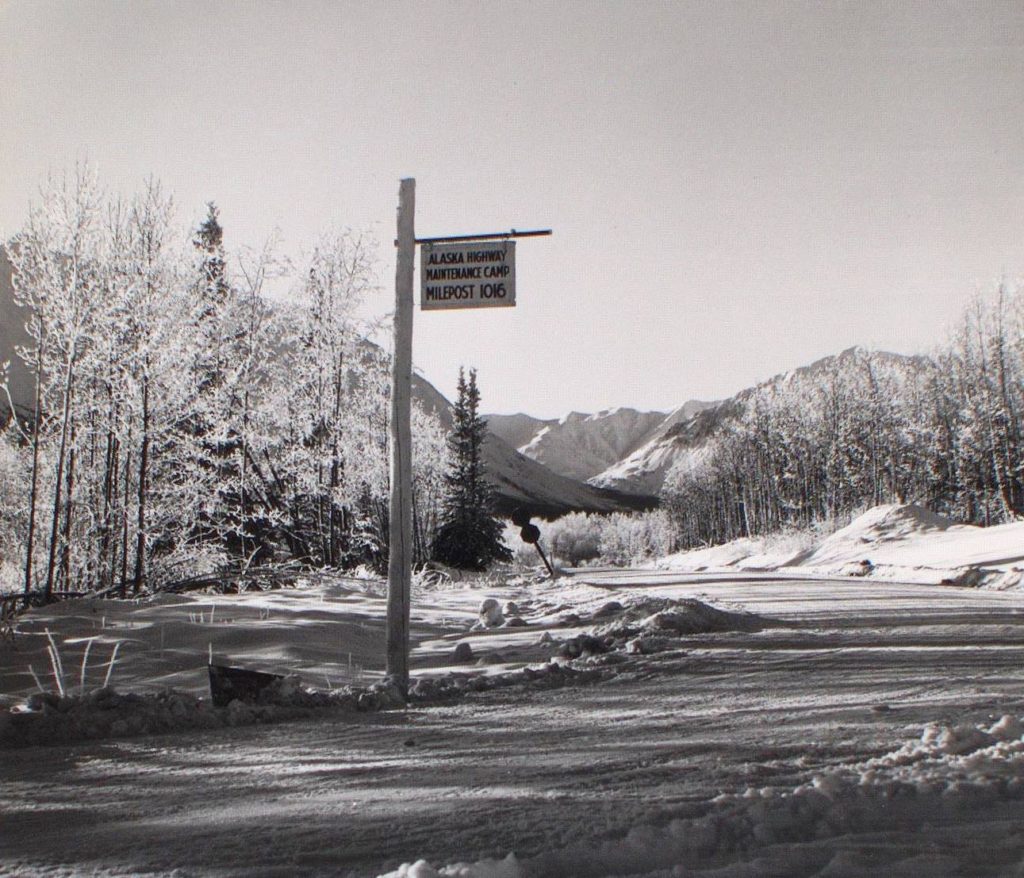

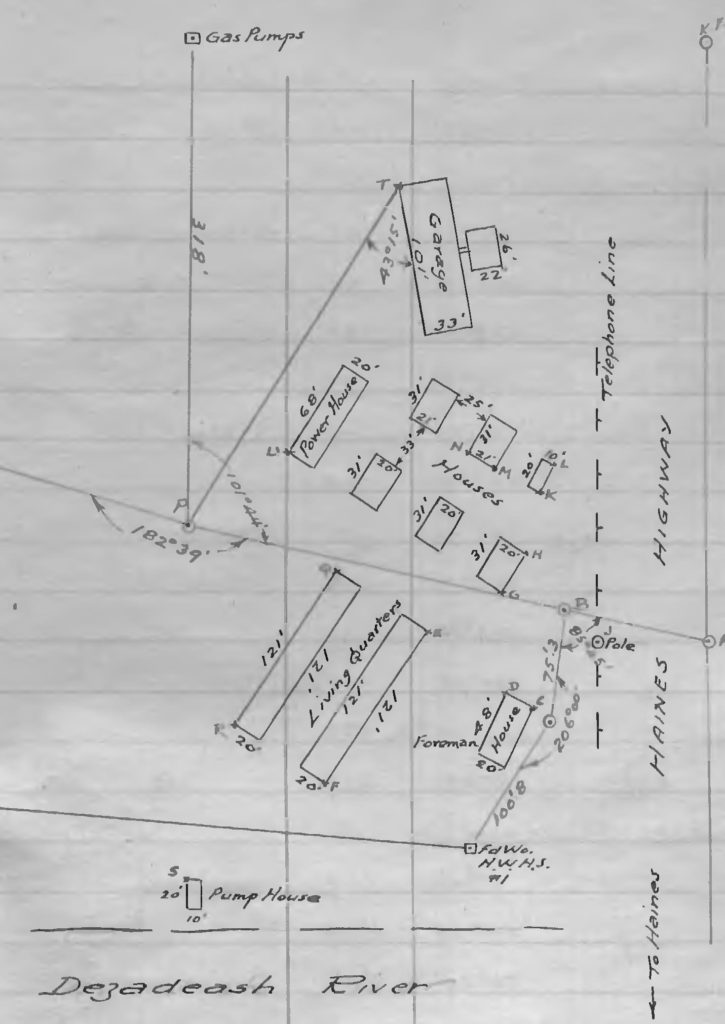

In 1948 Moose moved to the new community of Haines Junction, at Mile 1016 on the new Alaska Highway. It was located in an area he knew as Dakwäkäda (‘high cache place’) before the highway and town existed. This marked the start of Moose’s east-west life, as well as his life with Daisy David (Äma Kwānjia) of Aishihik, who he married at Haines Junction. He began work at the Dominion Experimental Farm at Mile 1019, then after it closed he went on to work for the Yukon Forest Service and Parks Canada, retiring in 1989 after many years of service with the federal government.

Moose and Daisy lived at Haines Junction for the rest of their lives. Moose served as CAFN Chief in 1975-76 and several terms as Elder Councillor, where he was an authority on cultural matters. Daisy died in July 2010 and Moose followed not long after in February 2011. They are buried in the CAFN cemetery at Champagne.

Coffee Breaks with Moose

At some point in the latter 1990s, Moose began occasionally coming into the CAFN office where I worked and seating himself at the meeting table, where somebody would invariably bring him a coffee or tea. I began joining him there and it didn’t take long for me to start really enjoying these interactions, which ended up going on for a number of years.

When these coffee visits started, Moose was getting into his mid-70s, but he seemed quite at ease sitting and bantering with younger people in an office environment. He had a sharp sense of humor that emerged more as he got comfortable there.

After Moose’s visits began to become routine, the start of our conversations did as well. They typified his humor and way of looking at things, and would almost always go something like this:

Gord: “Hi, Moose, how are you doing today?”

Moose: “Not too bad”.

Gord: “And what are you up to today?”

Moose: “Nothing. Just busy doing nothing”.

Gord: “Well, you must need a break then, I’ll get you a coffee”.

Moose: “OK, I’m getting tired from doing all that nothing”.

Then when Moose was getting ready to leave, he’d say something like, “Well, I better get back to doing nothing. I don’t want all that doing nothing to pile up on me”.

Even Moose’s way of drinking coffee and tea were things that caught my attention. I had never known anyone to hold a cup with their thumb through the handle, rather than two or three fingers as most of us do. I tried it and discovered that it takes more thumb strength than I possess to comfortably hold a cup that way. When he had tea, he stirred the teabag around for a minute to hasten the steepening, then plucked it out of the near-boiling water with his fingers and squeezed every last drop out of it.

I wish I could remember all the things from Moose’s unique sense of humor that caused me to have a good laugh. When he passed away, I wrote a few down so I wouldn’t forget them, although I don’t think I will forget these ones:

One cold, rainy September day Moose said “Ever since they started calling us First Nations, we don’t get no more Indian Summer”.

Moose and I were sitting at the table one day and a staff person came out of her office and said, “Moose, I need your knowledge and wisdom for something”. Moose must have been enjoying his coffee break because he replied to her, “No, I don’t have it. I left it at home today”.

Moose came in for coffee one time after he had just been to the doctor. He said the doctor came in and asked him “What can I do for you today?” Moose responded to him “You can’t do anything for me unless you got a pill for ‘old’”.

Moose in the Bush

The first time I ever encountered Moose in the bush was in about 1990 and not in the Haines Junction area, but in the eastern Yukon near the far end of the North Canol Road, of all places. I was there hunting with my brother-in-law Ernie MacKinnon when along came Moose and another elder, Hayden Woodruff. We chatted a bit and I remarked on how nice the country is up there, to which Moose agreed, but said he felt uncomfortable because it wasn’t his country. I was struck that Moose, a Yukon First Nations person, would feel that way only a few hundred miles from where he lived. I never did ask him if he actually hunted there, but it would not surprise me if his ‘rules of respect’ kept him from taking an animal from what he saw as someone else’s country.

Our coffee breaks at the CAFN office provided an opportunity for Moose to tell me things about the land and history based on his experiences and stories. I had confidence in what he said because if he didn’t know the answer to a question, he would say so rather than speculate or guess. He also wanted to have things he knew about documented before the knowledge was lost with him, which eventually led to us undertaking some trips out onto the land.

Moose’s physical limitations due to age and health didn’t allow us to do anything too rugged, but it was obvious that he enjoyed getting out and doing what we could. In looking for the things he wanted to be recorded, his ability to find something or to describe its location many years after he had last seen it was impressive, and always proved his knowledge and recollection to be accurate.

(photo courtesy of Champagne & Aishihik First Nations)

One example was an old carved face in a tree that marked the birthplace of a person. It was in a non-descript place in the bush, but Moose managed to find it in a short time after not having seen it since he was a teenager in 1940. On our way to look for it, he said that maybe after all these years the carving would be way up high as the tree grew up. I started to explain in all seriousness that it doesn’t work that way, until I noticed his sly grin.

Another example was a large high cache Moose knew of near Dezadeash Lake, but wouldn’t take me to in person because his Dad had told him he should stay away from there. Moose didn’t question directions like this, and though he had either never seen it himself or at least not since he was young, I was able to easily find it based on his description of the location.

Moose occasionally talked of a trail his family and others used between Hutchi and Klukshu that was an alternate to the more regularly used route through Champagne. We went out to an area near Kathleen Lake and walked into the bush a bit until he pointed out the trail as if it was obvious. I had to look hard for the subtle evidence of it, but the trail eventually revealed itself, many decades after it had last been used.

Looking Back

Moose passed along many pieces of this sort of land and heritage information to me and others. I am glad I made the notes that I did, but wish I had been able to record everything I heard him talk about. He was one of the last of the ‘before the highway’ people who could talk first-hand about life in this area of the Yukon before that event changed things dramatically.

There were occasions when Moose came into my office when I was busy and didn’t feel I had the time to have a coffee and conversation break with him. Looking back, I am glad I made myself do so, and in the end whatever work I was doing right then was undoubtedly not near as meaningful as time with Moose.