Around 10 AM on November 17, 1900, on a hillside along the Yukon River eight kilometers downriver (north) of the small settlement of Hootalinqua, woodcutter George St. Cyr with his loaded rifle confronted another woodcutter, James Davis. After a few terse words between them, St. Cyr’s rifle discharged into the chest of Davis, who slowly died on the spot.

The shooting death of James Davis led to a coroner’s inquest at Hootalinqua, followed by a trial in Dawson City that resulted in George St. Cyr spending the rest of his life in prisons and asylums. A peripheral witness to the shooting, William Clethero, went on to have a family and make the Yukon his permanent home.

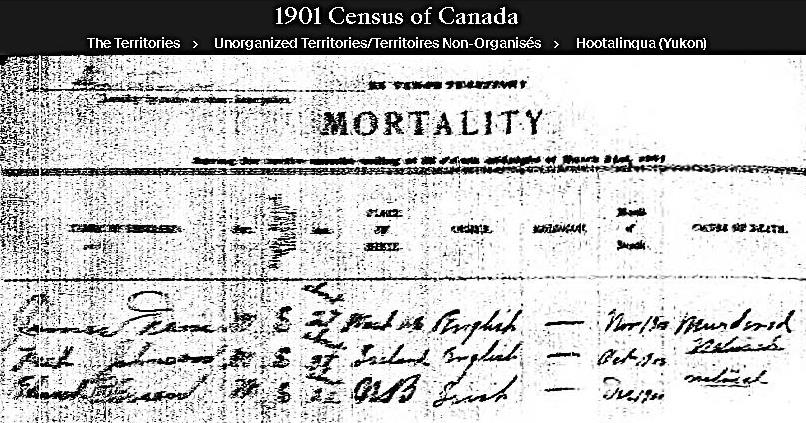

James Davis’s death is recorded in the 1901 Canada census, even though he died in late 1900. There were 49 living people listed in the census for Hootalinqua, most identifying themselves as miners or woodcutters, along with a few merchants and North-West Mounted policemen. The last page of the census is titled ‘Mortality’, where three men who did not live to see 1901 are recorded. The first entry is for Davis, noted as a 27-year old single man (he was actually 33) from Washington, USA who was murdered in November 1900.

(1901 Canada Census on Ancestry.com)

The line on the census mortality page records James Davis’s death, but does not show that he had a life eight kilometers down the river from Hootalinqua where he cut fuelwood for the steamboats that plied the Yukon River. There is not a lot of information about his life, but a semblance of it can be told and about what led to its ending.

It is unfortunate that other news events captured Yukoners’ attention at the same time, taking the focus away from Davis’s life and senseless death. In addition, newspaper coverage of the trial of George St. Cyr provided virtually no information about Davis and sometimes even got his name wrong. As a result, the murder of the woodcutter James Davis on a hillside overlooking the Yukon River near Hootalinqua has gotten little attention in Yukon history.

Background

Hootalinqua

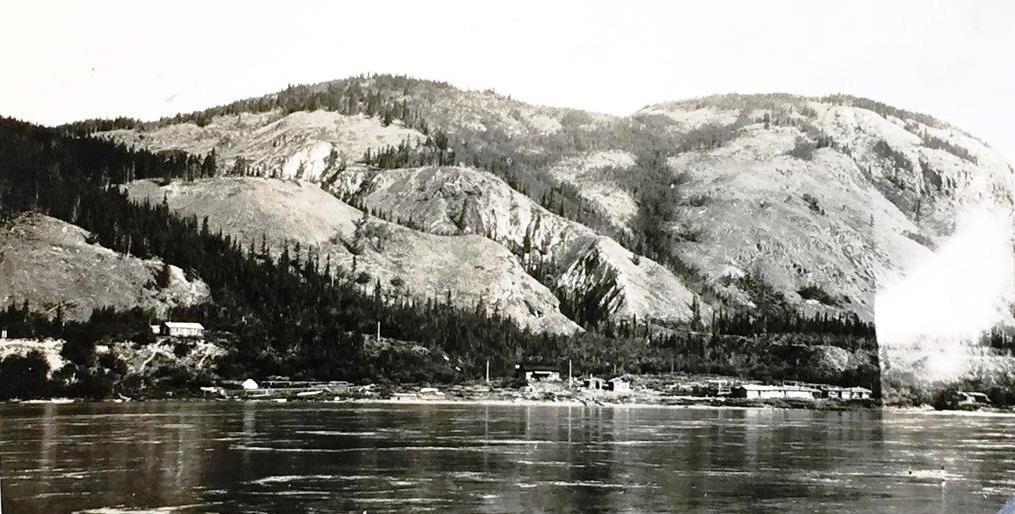

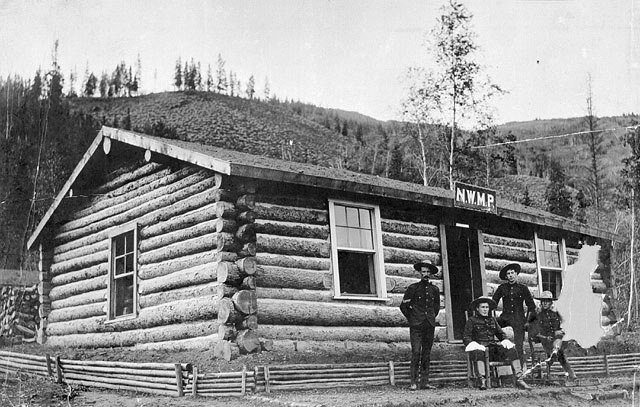

Hootalinqua is a small abandoned settlement along the Yukon River 136 kilometers north of Whitehorse, located on the left (west) bank of the river just below the mouth of the Teslin River. This central location served as a First Nation meeting place and fish camp before prospectors travelling over the Chilkoot Pass began exploring this part of the country in the 1880s. It began as a settlement early in the Klondike gold rush and became a year-round one in 1897 when a store and roadhouse along with a North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) post were established there.

The main rush of 1898 resulted in considerably more people passing by on their way to the goldfields of the Klondike, both by boat in the summer and along a trail on the Yukon River ice in the winter. A number of people remained in the Hootalinqua area, particularly once a gold strike was made in 1899 on Livingstone Creek to the southeast that was accessed via the Teslin River. By 1900 James Davis, George St. Cyr, and William Clethero had settled in the area to cut wood in the winters to sustain themselves and possibly also to support gold mining dreams they may have had.

(Yukon Archives, Christopher Everett Webb fonds, Acc. 80/87, #22 – photo has been cropped)

(Gord Allison photo)

Two significant developments in 1899 changed things at Hootalinqua. The first was the construction of the Yukon Telegraph Line passing through that summer, bringing improved communication with the outside world. The telegraph service enabled the NWMP in both Dawson and Whitehorse to be notified of the murder of James Davis and for the investigative and justice wheels to be put into motion fairly quickly. A year earlier, relaying of such news from this location would have taken many days or even weeks in mid-November, the time of year known as ‘freeze-up’ when the steamboats were no longer running and overland travel was difficult.

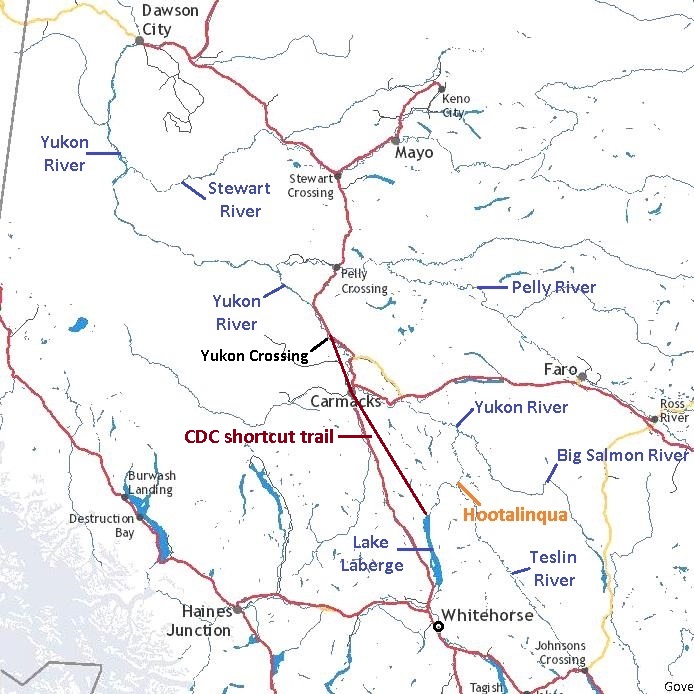

The second development in 1899 was the abandonment of a section of the Yukon River winter trail between Whitehorse and Dawson that went through Hootalinqua. In the winters previous, this trail was on the ice of the river, but in the fall of 1899 a shortcut trail called the ‘CDC Cut-off’ (for Canadian Development Company) was cut out over land from the north end of Lake Laberge to the Yukon Crossing area north of Carmacks. This eliminated a section of the longer and more dangerous trail along the river ice and bypassed Hootalinqua, meaning that little winter traffic now came through the settlement. For the NWMP escorting the accused murderer and the witnesses to the trial in Dawson at freeze-up time in late 1900, the new shortcut trail provided a safer way to travel.

(GeoYukon)

As the early 1900s moved along and the Yukon’s population and activity began to decline, so did that at Hootalinqua. By 1905 the NWMP post became seasonal, open only in the summers because the winter traffic didn’t warrant it being staffed. The settlement was more or less abandoned in the mid-1920s with the closing of the telegraph office in 1925. Apart from the telegraph office and another building, along with other remnants scattered about, the nearby cemetery is the lasting physical evidence of life that once carried on at Hootalinqua.

The Woodcutting Life

The Klondike gold rush gave rise to a large steamboat industry for transportation, along with a woodcutting industry to support the boats’ need for fuelwood. Steamboat history gives captains and pilots all the fame and glory, but their professions and the industry as a whole depended on the hard labor and entrepreneurial drive of woodcutters. Woodcutting camps sprang up all along the Yukon River and other valleys where there were good sources of timber and nearby riverbanks that could accommodate steamboats pulling into and loading on the wood.

Most woodcutters cut hundreds of cords of wood over the course of the year, all by axe and cross-cut saw and handled much of it manually. For many years they were called ‘woodchoppers’, undoubtedly due to the prevalence of axes in their work, but woodcutters became the more common term. A range of hills to the east of the Yukon River in the Yukon Crossing – Five Finger Rapid area was named Woodcutters Range in their honor. (see link to related Finley Beaton woodcutter article at end)

The woodcutters lived their lives in log cabins and occasionally in tents, sometimes relatively isolated from other people and in some situations in close proximity as was the case with James Davis and George St. Cyr. They operated under contract to the steamboat companies, which from 1900 on was primarily the British Yukon Navigation Company, a subsidiary of the White Pass & Yukon Route. Some woodcutters worked year-round at their woodyard while others appear to have dabbled in mining or other pursuits in the summers. Some did the opposite, such as roadhouse operators who ran those businesses in the winters and cut wood in the summers.

As the woodcutters moved further away from the river to access new areas of timber, horses or dog teams were used to move the wood out to the riverbank. This was usually done in winter when the ground was frozen and the wood was easier to move, either by dragging or carting in sleighs. The wood was cut into four–foot lengths and piled four feet high, with an eight-foot row constituting a cord, which was the basis of payment. Long rows of this cordwood were stacked along the riverbank to be available for loading onto the steamboats, which made frequent stops for ‘wooding up’.

(John Stelfox photo)

In the early years of the steamboats large areas called timber berths were allotted to companies that cut fairly large volumes of wood. These areas were mapped and marked out and the companies had the exclusive rights to harvest wood within them. Individuals were normally issued timber permits and a woodcutter could usually operate in one area for several years before having to move.

The timber permits involved no exclusive cutting rights nor permit area boundaries laid out. A letter written by the Crown Timber and Land Agent at Fort Selkirk in February 1901 contained this recommendation: “that cordwood permits be made ‘exclusive’, that is that not more than one permit be given for any one locality … I was given to understand that if this had been law heretofore, St. Cyr would not be accused of murder, as … who had prior claim to a given locality was the original cause of the trouble arising between Davis and St. Cyr”. While timber permit areas may have been a factor in the relationship between the two men, the records show that it would have been only one among others that led to their fatal encounter.

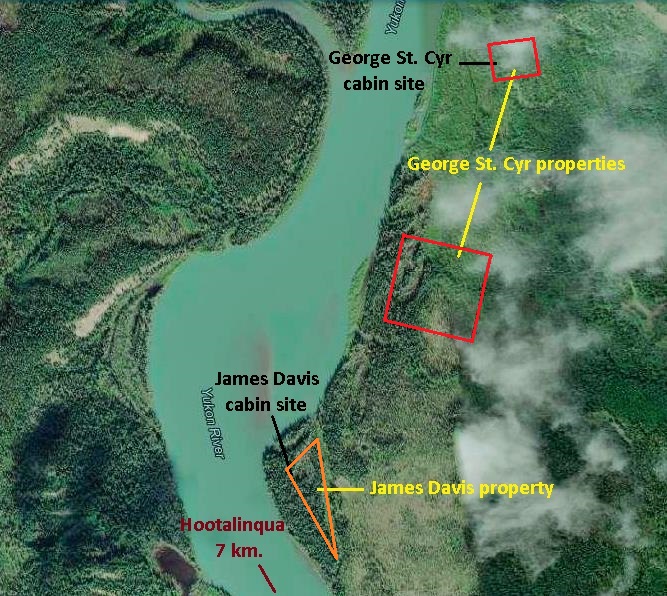

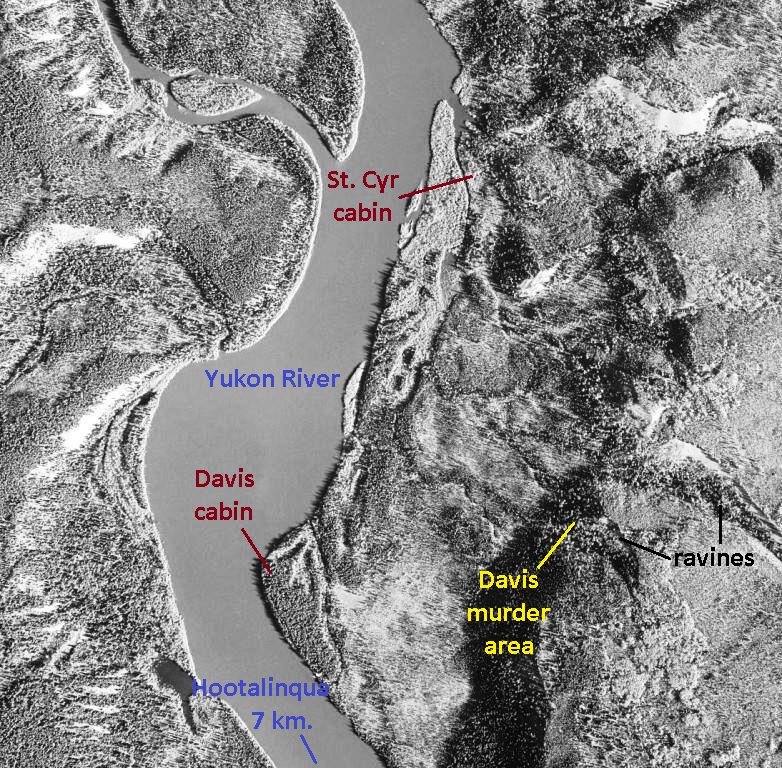

At the time of that encounter in November 1900, James Davis and George St. Cyr were living and working near each other along the Yukon River downriver and on the opposite (east) side of the river from Hootalinqua. Davis and William Clethero were woodcutting partners who lived in Davis’s cabin seven kilometers from Hootalinqua. They had an uneasy relationship with St. Cyr, who lived in his cabin a kilometer further downstream.

James Davis

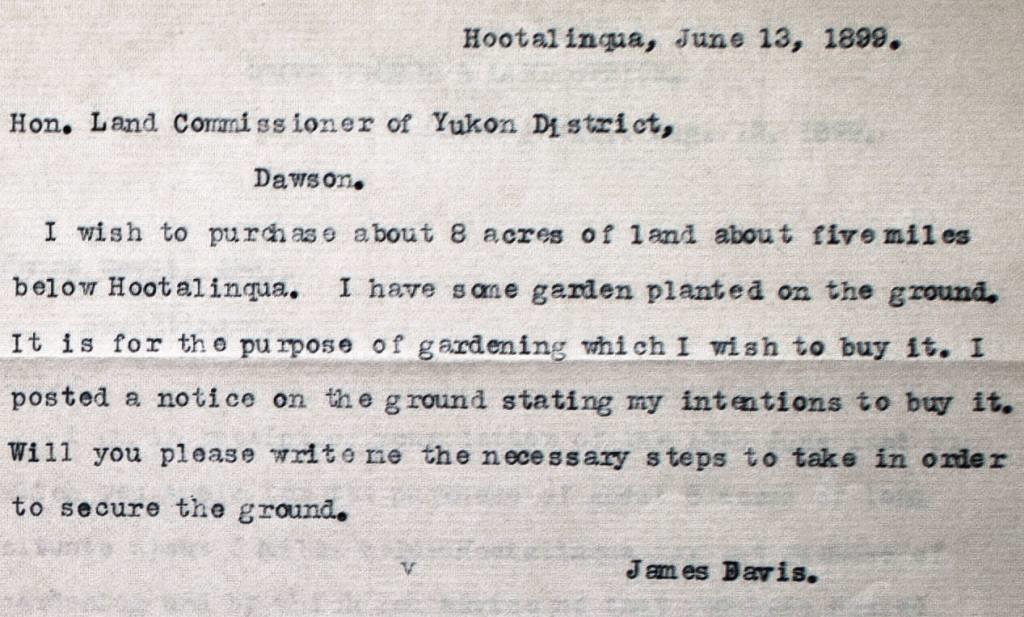

James Davis was born in 1867, the third of fourteen children born to John and Caroline Davis, a well-to-do business couple in Walla Walla, Washington. James left that life to join the Klondike gold rush, with records indicating that he came into the Yukon in 1898 and was settled near Hootalinqua by June 1899. On the 13th of that month, he applied for eight acres of land downriver from the settlement, in the vicinity of where George St. Cyr also obtained land. Davis stated that he wanted the land for gardening, and had already planted some garden there. No mention is made of a cabin, but it is likely he had built his cabin there or was working on it.

(Yukon Archives, GOV 3683, file 11)

Davis ended up with only 2.84 acres of land, perhaps because the response to his letter stated that he would be required to pay $20 per acre plus the cost of survey, estimated at $100. He asked for some time to come up with that amount of money, so at some point he likely decided to reduce the size of the parcel for monetary reasons (although in the end he only had to pay $10/acre and $50 for the survey). His land was surveyed along with St. Cyr’s in July 1900.

George St. Cyr

George St. Cyr was born in about 1865 in Quebec, the fifth of nine children in a prominent family. He headed west as a young man and was in British Columbia by 1891, probably because his older brother Arthur was there. Arthur was a Dominion Land Surveyor and in the late 1890s carried out exploratory surveys in northwestern BC, the country to the north and east of Teslin Lake, and the Hootalinqua and Big Salmon Rivers. He also was involved in the International Boundary Survey as well as the survey of sections of the Yukon-BC boundary between Teslin Lake and the Alsek River.

In 1894 and 1895 George was working on the survey of the Alaska-BC boundary between Glacier Bay and Yakutat Bay in southeast Alaska/northwestern BC. On this and perhaps other projects, George may have been working with his brother Arthur.

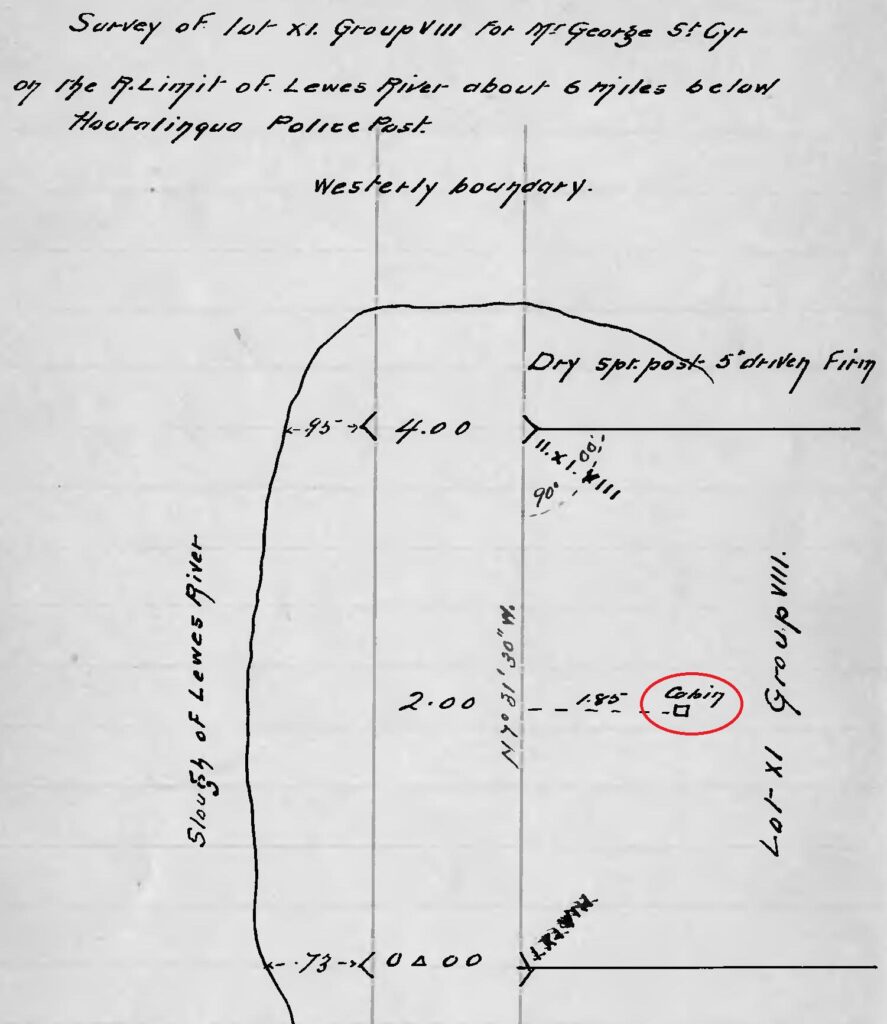

In 1899 George came to the Yukon and began living in the Hootalinqua area sometime that year. At some point he applied for and was granted two parcels of land for unspecified purposes down the river (north) from the settlement, and these were surveyed for him in July 1900.

William Clethero

William Clethero (often spelled Cletheroe, and at the time of the murder was spelled Clithero or Clitheroe) was born in 1876 on the Falkland Islands in the Atlantic Ocean near the south end of South America. His parents were of English origin and he had two older sisters and a younger brother. When Clethero was 23 years old in 1899, he arrived in Canada and by the following year was at Hootalinqua, where he became a woodcutter, first as a partner with George St. Cyr and then with James Davis.

The Davis and St. Cyr Properties

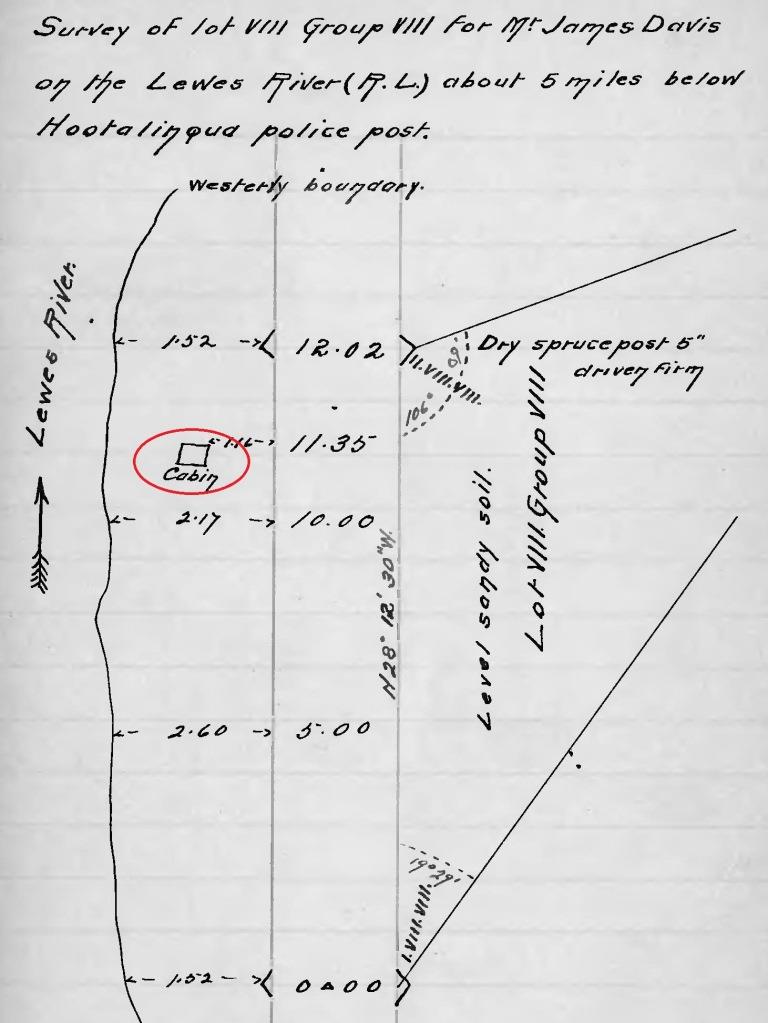

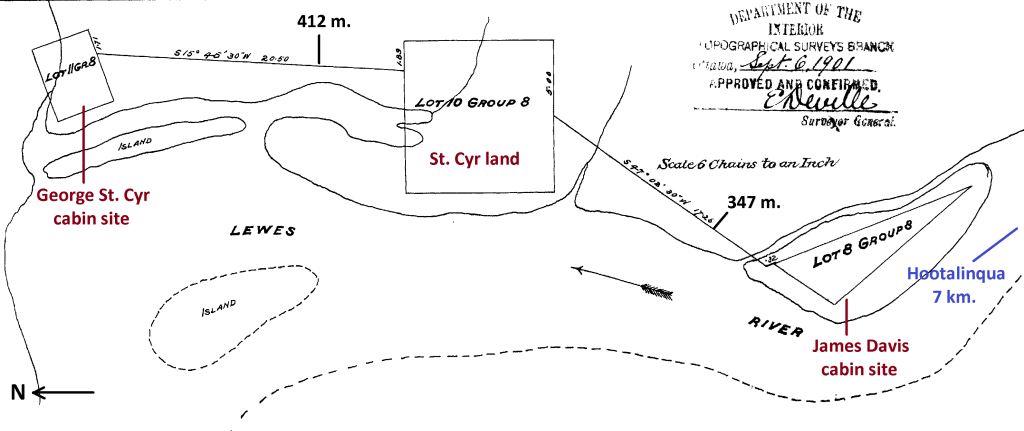

This article originated from research into three parcels of surveyed land situated within a one-kilometer stretch seven to eight kilometers north of Hootalinqua on the east side of the river. They were surveyed in July 1900 by Dominion land surveyor Charles MacPherson of Dawson for the two woodcutters who were the principals of this story, James Davis and George St. Cyr.

The existence of these three parcels bunched together in this setting at a distance from the settlement piqued my curiosity. Research into them and the people they were surveyed for soon revealed the story of James Davis’s murder. It also showed that titles to the land parcels had not yet been granted to Davis and St. Cyr before the murder event disrupted everything.

The first parcel going downriver (north) was about seven kilometers from Hootalinqua, a 2.84 acre (1.15 ha.) triangular-shaped plot of land that James Davis had been granted. It was situated on relatively flat ground on a point of land with the river on the west and north sides of it. Davis’s cabin was located close to the river, just off his land near its northwestern corner.

(Canada Lands Survey Records, FB 6430, p. 33)

About 500 meters to the north of Davis’s property was a 10-acre (4.05 ha.) square piece of land belonging to George St. Cyr. It was on a gently rolling slope with a small spring creek running through it, and at the time of the survey was described as a mixture of open country, burned timber, and green bush. It had no human developments shown on it, and the intended need and use of this parcel is unknown.

Another 500 meters further north of St. Cyr’s 10-acre parcel was the second piece of land belonging to him, this one a square parcel of two acres (.81 hectares) in size, with relatively low land on the river side that appears subject to occasional flooding. St. Cyr’s cabin was located on this lower land and situated about 140 meters back from the river, with a small slough in between. Behind the cabin the land rises sharply up a small hill, and a small stream of clear, cold water from the hills passes by not far from the cabin site.

(Canada Lands Survey Records, FB 6430, p. 42)

The surveyor MacPherson also produced a sketch map showing all three lots and the spatial relationships between them. The straight-line distance between the two cabins was slightly over a kilometer.

(Canada Lands Survey Records, #8940)

The image below shows this same spatial relationship of the lots on the Yukon River on modern imagery.

(GeoYukon)

The reason(s) for St. Cyr and Davis applying for and acquiring their land parcels remains undetermined. They paid $10 per acre for their properties along with a $50 survey fee, which demonstrates a degree of seriousness on their part when they were paid only a few dollars per cord of wood that they cut, hauled and stacked by hand. Perhaps both men had grander and longer-term visions for their futures in the Hootalinqua area.

Whatever reasons Davis and St. Cyr had for going through the process of applying for and paying for their land parcels and the survey of them remains unclear. Perhaps both men had grander and longer-term visions for their futures in the Hootalinqua area.

The Murder, the Inquest, and the Trial

Lead-up to the Murder

The story of what led to the murder of James Davis and its aftermath appears to begin on February 8, 1900. According to St. Cyr, that is when he and Clethero became woodcutting partners and stayed together in St. Cyr’s cabin. The partnership ended fairly abruptly a few months later on May 28, 1900.

On the day before this, Clethero told St. Cyr that he wanted to go home (presumably meaning the Falkland Islands) because it was too dull at Hootalinqua. He was expecting a letter with money for him to make the trip, and said that he did not want to return home a pauper. St. Cyr told him he would go to Hootalinqua the next day to get him some money to go back home, to which Clethero replied that he would work for another month.

The next morning St. Cyr poled his canoe the eight kilometers up the Yukon River to Hootalinqua and got a $300 loan from Dan Snure, the roadhouse operator. On his way back down the river, St. Cyr stopped at Davis’s cabin to deliver him something, whereupon Davis mentioned that he had had a visit from Clethero.

On arriving at his own cabin, St. Cyr found Clethero with his belongings packed, which he quizzed him about, as well as why he visited Davis in his absence. Clethero replied that he went to ask Davis if he could be his woodcutting partner because of some quirks that St. Cyr had. St. Cyr took offence at this and a physical altercation ensued between them, the details of which differed in their testimonies.

Clethero left for Davis’s cabin a kilometer to the south and the next day walked along the river up to Hootalinqua and returned with NWMP Cst. Ferris to St. Cyr’s cabin. Clethero gathered his belongings he had left there and was given the money St. Cyr had gotten for him, then in the company of Cst. Ferris went to his new lodging in Davis’s cabin.

St. Cyr and Clethero gave different information about their interactions in the time between the dissolution of their partnership in late May and the day of the shooting in mid-November. St. Cyr said he ran into Davis twice and Clethero once, but did not say anything about the context or tone of these encounters. He claimed to be aware that Clethero and Davis were “blackmailing” him, a term that he understood meant to “slander or take away a person’s character”. He did not say in what manner they were doing this or how he knew about it.

As for Davis, St. Cyr said that he had no hard feelings toward him, even though he had once found him cutting on his land, which Davis explained was because Clethero had suggested he go there. St. Cyr also said that he and Davis had owned a scow and a raft together, then Davis sold the raft and kept the scow, but St. Cyr had long since forgiven him for this.

Clethero’s testimony differed from St. Cyr, saying that he had never spoken with him since their partnership dissolved and bore no ill will toward him. He surmised that St. Cyr had some sort of grievance with him because he never visited, and also believed that St. Cyr blamed Davis for taking Clethero on as his woodcutting partner.

Joseph Primeau, a camp cook and woodcutter who had met St. Cyr previously in Vancouver, stayed with him for a time in August 1900 at his cabin below Hootalinqua. Primeau said later that he was aware of the disagreement between St. Cyr and Clethero and the dissolution of their partnership, but he could not say what St. Cyr’s disposition was toward Clethero and Davis.

Davis and Clethero worked together from the formation of their partnership in late May and through the summer, taking out a timber permit for 150 cords of wood on August 31. Whatever interactions they may have had with St. Cyr working in relatively close proximity to them, it all came to a head on the morning of November 17, 1900.

The Murder and Investigation

The following account of the murder of James Davis by George St. Cyr and the investigation of it is assembled primarily from two sources: statements given at a coroner’s inquest at Hootalinqua by St. Cyr and five witnesses, the main one being William Clethero; and newspaper coverage of the trial in Dawson. The witness statements are contained in Library & Archives Canada RG18-A-1, Volume 236, File 664-02 and the trial reporting was by the Dawson newspaper Daily Klondike Nugget in its editions of February 4, 5, and 7, 1901 (by the February 7 edition the newspaper had changed its name to the Semi-Weekly Nugget).

The testimonies and information from these processes generally agreed on what transpired on the day of the murder. What is certain about the death of James Davis near Hootalinqua on that November day is that he was killed by the discharge of a rifle in the hands of George St. Cyr. What is uncertain is why and how it discharged, as the only person who knew that was the one who held the rifle.

William Clethero was not a witness to the shooting, but he was within sight of where it happened and heard a shot. He had also been involved in the circumstances that brought on the tension that led to the conflict. The validity of some of the information provided by St. Cyr and Clethero about these events was undoubtedly influenced by their self-interest and attitudes toward each other.

In the morning of November 17, Davis and Clethero went out to work cutting trees on the hillside straight back (east) from their cabin, a distance that the NWMP later estimated to be 600 yards. Around 10 AM, Clethero broke the handle of his axe and told Davis he was going back to the cabin to repair it and would prepare their lunch. While doing this he heard a gunshot, and a short time after went outside to dump out some water and saw a man walking away from where he knew Davis was working. He thought the man was George St. Cyr.

(Gord Allison photo)

Earlier that morning, a kilometer to the north, St. Cyr also left his cabin after breakfast to go cut cordwood. After working for a while, he heard some chopping sounds from the southeast direction and thought that someone might be cutting on ‘his land’. He wondered if perhaps Davis and Clethero “were still contemplating some further outrages”. St. Cyr laid down his axe and started toward where the sound came from, “fully intending to have some kind of explanation from them on their past behaviors”.

(Gord Allison photo)

St. Cyr walked in the direction of the chopping until striking the south boundary of his 10-acre parcel of land and followed the survey line to the southeast corner post of the property. He continued in a southerly direction that took him uphill into a ravine and when he got to the far edge of it, the cutting noises stopped. He was by then close enough to the two men that he could hear them talking and said he heard Clethero make a derogatory remark about him. He also said he heard Davis tell Clethero not to worry about St. Cyr, as they will soon have him out of the country. St. Cyr said they then proceeded to call his parents offensive names.

Under later cross-examination questioning why he continued going toward the chopping sounds even after he had determined they were not coming from his land, St. Cyr said he wanted to ask Davis why he had stopped coming for visits. He also wanted to know if he and Clethero were plotting to cut timber on his (St. Cyr’s) land.

When St. Cyr “could endure [the insults] no longer”, he walked back to his cabin and put some cartridges in his .30-.40 Winchester rifle, including one in the chamber. At the inquest he said the gun was “to make Davis and Clethero apologize for past and present insults”, but at his trial he also said he feared Clethero, suggesting that the rifle was also taken along for potential self-defence.

St. Cyr saw on the clock in his cabin that it was now 9:30 AM and began the walk back the way he had come, following the ravine up to a place he could cross it, then continued on an uphill angle a few hundred feet more to another ravine. When he got near the top edge of it, he heard somebody chopping and saw the back of a man’s head. He went further to within 25 or 30 feet of him on the uphill side, then stood there watching him. The walk from his cabin had taken about 20 minutes and it was now approaching 10 AM.

(National Air Photo Library, A28543, #71)

According to St. Cyr’s testimony, after several minutes the man chopping wood turned and it was Davis, who was startled upon seeing St. Cyr. He gave a terse acknowledgement before starting to chop the tree from the other side. St. Cyr asked Davis “why he and [Clethero] had been aggravating him the past months and insulting him?” Davis didn’t answer, so St. Cyr asked him to repeat what he and Clethero had been saying about him and his parents earlier, to which Davis uttered something that St. Cyr did not understand.

St. Cyr said he had the gun under his right arm, not at his shoulder, and in his nervousness and “the excitement of the moment”, it went off. Davis’s arms went up and he fell back into a sitting position facing out over the river valley. St. Cyr said he thought Davis was ‘shamming’ (faking), so walked closer to him and asked if he was hit. There was no answer, but he noticed a few drops of blood on the snow and asked where he was hit, but again got no answer. Davis sat there rocking and moaning with his arms crossed over his chest, saying only “my God” a few times. St. Cyr told him he was sorry this had happened.

From the elevated site of the shooting on the hillside there was a clear view to Davis’s cabin, as the timber in the valley below had already been cleared for fuelwood. St. Cyr could see Clethero outside the cabin and shouted at him a few times, but he didn’t seem to hear. He then fired a shot into the air to get Clethero’s attention in the hope that he would come and help get Davis off the hill and to his cabin. St. Cyr said that Clethero left the cabin and “ran away”.

(Gord Allison photo)

St. Cyr said he remained with Davis for about 30 minutes, occasionally hollering for Clethero. During this time Davis changed his position to lie on his stomach with his left hand under his chest and right hand stretched out on the snow. St. Cyr went and lifted the exposed hand up and it was limp, but Davis was still breathing. St. Cyr tried to lift him up to see if he could carry him, but he was too heavy. St. Cyr put him back down as he was, then walked the kilometer back to his cabin, gathering up his woodcutting tools on the way.

Clethero had heard a gunshot while preparing lunch in the cabin, but his testimony does not indicate he heard two shots as St. Cyr claimed to have fired. When Clethero went outside to dump some water, he saw a man with a rifle that he thought was St. Cyr walking away from where he and Davis were working. Clethero put some wood on the fire and said he heard the faint cry or moan of a man, which he thought could be Davis in distress.

About 15 to 20 minutes after hearing the gunshot, Clethero armed himself with a rifle and set out to where Davis was and found him lying down and bleeding. Upon asking him what the matter was, Clethero claimed that Davis said St. Cyr had shot him and he didn’t know why, and that he would kill him (Clethero) too. Clethero later testified that he took the rifle for protection because the cry of distress he heard might have been the result of St. Cyr shooting Davis. He said Davis had feared that St. Cyr might “lay waiting” for him sometime.

There was a hand sleigh at the site, but Davis was a heavy man and the fallen timber all around and lack of a trail in the 14 inches of snow prevented Clethero from being able to move him. Later when asked why he didn’t seek out St. Cyr for assistance, Clethero said he would not do that because of what Davis had told him about being shot by St. Cyr.

Clethero told Davis that he would go get help, but noted that his eyes were sunken back in his head and he appeared to be dying fast. Clethero wrapped Davis’s parka around him and then departed directly on the seven-kilometer walk to the Hootalinqua NWMP station to report what had happened.

Back at his cabin, St. Cyr unloaded his rifle and put it in the gun rack without cleaning it, then locked up the cabin. He began to walk the eight kilometers to Hootalinqua to give himself up to the NWMP for accidentally shooting James Davis. He was on the trail behind Clethero on the walk that would take about two hours.

At first neither Clethero nor St. Cyr would have known that the other was on the trail. St. Cyr would have realized it when he came upon tracks in the snow heading south toward Hootalinqua, and Clethero may have thought that St. Cyr could be coming behind him. It was likely a very stressful walk for both of them, knowing what the other knew, and not knowing if the other was packing a gun.

Across the river from Hootalinqua, NWMP Corporal Charles Stewart and Constable Frederick Gardiner were cutting firewood for the police post when a man named William Mason summoned Stewart to his nearby house. There Stewart found William Clethero, who told him about what had happened downriver. The two NWMP members took Clethero across the still ice-free river in their boat, got some arms from the NWMP post, and then Stewart along with Cst. John Richardson and Clethero headed down the river to Davis’s cabin.

From the cabin the three men walked to the scene of the shooting and found Davis lying on his back deceased and his body beginning to freeze. Stewart observed that Davis had been in the act of cutting down a tree on a steep slope when shot and he and his axe fell where he had been standing.

Stewart and Richardson went to check out St. Cyr’s cabin and found it locked up. They cut the lock off with an axe to get inside, where they saw three guns hanging on the wall, two that were well-oiled and one that appeared to have been used.

They then went and caught Davis’s horse and used it to carry his body back to his cabin to thaw out. Upon examining it, they found that the bullet had entered to the left of the breast bone just below the collar bone and travelled back and down, coming out below the shoulder blade. The NWMP surgeon Dr. Hurdman in Dawson later testified that the described injury would likely rupture the aorta and other arteries, resulting in death within half an hour. Stewart and Richardson wrapped the body in a tarpaulin and put it in an outbuilding, then went into the cabin to spend the night along with Clethero.

Back at Hootalinqua, St. Cyr reached the point across the river at about 12:30 PM and went to the tent of an acquaintance, Louis Johnson, who was eating lunch and invited St. Cyr to join him. St. Cyr said he had no time because he was going across the river to give himself up to the police for shooting James Davis accidentally. Johnson was not aware of this, indicating that his tent must have been some distance from where Clethero had met up with the NWMP members a short time before.

Johnson then ferried St. Cyr across the river in a canoe, and when he got out of the canoe at Hootalinqua, the roadhouse and store operator Dan Snure along with others were on the shore. St. Cyr expected that Snure wouldn’t come and shake his hand under the circumstances, but he did as usual. St. Cyr said to him and the others that he would rather not speak with them right now and went to the NWMP post where he gave himself up to Cst. Gardiner and was fed lunch. This was three-quarters of an hour after Cpl. Stewart, Cst. Richardson, and Clethero had departed for the scene of the shooting. For St. Cyr, lunchtime in the Hootalinqua jail was the beginning of the rest of his life in custody.

The Inquest at Hootalinqua

The death of James Davis on November 17, 1900 occurred at a time of year when travel usually ceases where rivers are involved. The large rivers and lakes of the Yukon were its highways in 1900, even in the winters, but at the time of year in the late fall known as ‘freeze-up’, travel on the waterways stopped until the ice was solid enough to be safe. In mid-November, depending on the year and location, the large rivers of the southern and central Yukon usually have ice running in them or are frozen over but not yet safe for travelling on.

The Davis murder appears to have happened in a year of a late freeze-up, with the river still ice-free enough to be navigable by small watercraft. However, the murder investigation and the inquest held at Hootalinqua, along with the subsequent transport of the alleged murderer and witnesses to Dawson, all took place during the period when the river would be freezing over but not entirely suitable for travel. This factor is not mentioned in the records of the murder and follow-up events, but for the police it must have posed considerable challenges that had to be overcome in the pursuit of justice and respect for a murder victim.

NWMP Superintendent Philip Primrose in Dawson received word of the murder by telegraph later the same day it happened, and the following day wired Inspector John McGibbon in Whitehorse to go to Hootalinqua to investigate. McGibbon likely left Whitehorse the next day, November 18, but there is no record of his trip there or by what means. He would have had to travel north on or beside the 37 kilometers of Yukon River to Lake Laberge, then along the 50-kilometer long lake that was probably recently frozen, and down or beside the 50 kilometer section of Yukon River from Lake Laberge to Hootalinqua that may have had ice running in it.

A hint about the difficulty of McGibbon’s trip to Hootalinqua is contained in a Dawson Daily Klondike Nugget newspaper article ten days later, which said that as of the evening of November 28, Inspector McGibbon had not yet arrived there. The article said the NWMP believed “the cause of the officer’s not yet having reached [Hootalinqua] is due to the bad travelling between Whitehorse and that place”. It appears that it took McGibbon around 10 days to travel the 136 kilometers from Whitehorse to Hootalinqua, an average of only 14 kilometers or so per day, undoubtedly due to ice conditions.

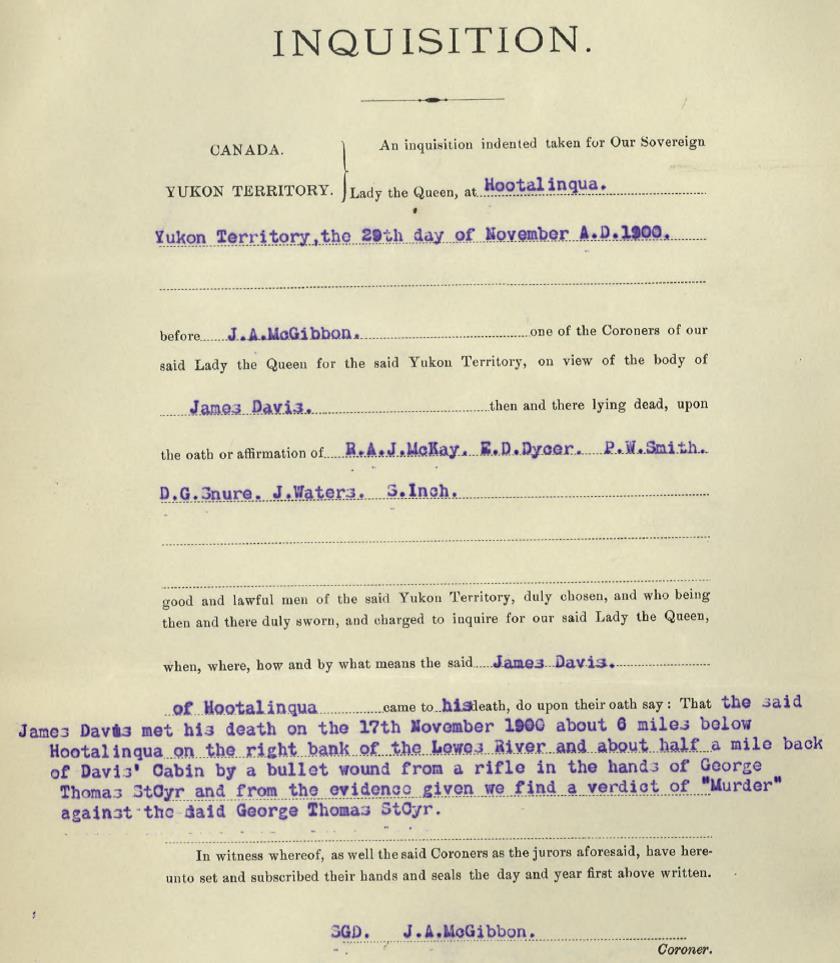

When he finally arrived at Hootalinqua, Inspector McGibbon assumed the role of coroner and impanelled a jury of six local men on November 29. The jury observed McGibbon’s questioning of six witnesses: the prisoner George St. Cyr; William Clethero, who had been in the vicinity of the shooting did not directly witness it; Louis Johnson, the woodcutter who was the first person St. Cyr talked to after the shooting; and the Hootalinqua-based NWMP members who investigated the incident, Corporal Charles Stewart and Constables John Richardson and Frederick Gardiner.

(Library & Archives Canada, RG18-A-1, Vol. 239, File 664-02)

At the end of each interview (other than St. Cyr’s) is the notation “No cross questions by Prisoner”, meaning that St. Cyr had the opportunity to cross-examine the people providing their information. This included the testimony given by William Clethero, who was near the shooting of James Davis and with whom St. Cyr had some animosity. Clethero would have had to answer Inspector McGibbon’s questions in St. Cyr’s presence in the confines of a relatively small room in the Hootalinqua NWMP detachment.

(Library & Archives Canada, #A202192)

The coroner’s jury found that “James Davis met his death … by a bullet wound from a rifle in the hands of George Thomas St. Cyr and from the evidence given we find a verdict of murder”. This finding by the jury was direction that a murder charge should be laid against St. Cyr, and it was followed by instructions from the NWMP to bring him to Dawson to stand trial. The wheels were promptly set in motion to get St. Cyr and the necessary witnesses to Dawson for a murder trial.

To Dawson for the Trial

The first step in bringing George St. Cyr to trial for murder was getting him and four witnesses the 550 kilometers from Hootalinqua to Dawson during the freeze-up. The witnesses, all of whom had also given evidence at the coroner’s inquest, were William Clethero, Louis Johnson, Cpl. Charles Stewart and Cst. Frederick Gardiner. The only records of this journey are the NWMP annual report for 1901 simply stating that “the prisoner was removed to Dawson to stand his trial” and a news article saying that St. Cyr was brought to Dawson in the charge of Cpl. Stewart. It is reasonable to assume that Stewart and St. Cyr travelled apart from the other three men to maintain separation between the accused and those witnesses.

The trip to Dawson probably commenced not long after the inquest at Hootalinqua held on November 29. Two weeks had elapsed since the murder of James Davis and in that time the Yukon River ice had likely formed and perhaps thickened enough that some or most of it could be travelled on. The method of travel may have been by dog teams if there were enough dogs available at Hootalinqua, otherwise they would have gone on foot and perhaps were later able to get onto a horse-drawn stage.

The route the men are most likely to have taken was southerly along the Yukon River to Lake Laberge, then westward across the north end of the lake to the northwest corner of it. There they would have joined onto a new 150-kilometer trail known as the ‘CDC Cut-off’ that had been constructed the previous year for the Canadian Development Company mail service. This trail, from the north end of Lake Laberge to near Yukon Crossing, north of Carmacks, had been built as a safer and shorter route by eliminating travel on about 265 kilometers of Yukon River ice.

When the Hootalinqua travellers came onto the cut-off trail at the north end of the lake, if they were on foot they may have been able to get a ride with a mail stage or one of the small independent stage line companies that were providing this service between Whitehorse and Dawson. They also would have had the option of staying in some of the many roadhouses that had been established along the trail, rather than camping out.

By whatever means they were travelling, near Yukon Crossing they would have reached the end of the cut-off land trail and got onto the Yukon River winter trail for the rest of the journey to Dawson. In the Minto area they would have passed by the spot on that trail where one year previous, on Christmas Day 1899, Frederick Clayson, Linn Relfe and Lawrence Olsen were ambushed and killed by George O’Brien and perhaps an accomplice.

Cpl. Stewart and St. Cyr arrived in Dawson at the end of the last day of 1900. They had been on the trail the better part of a month, meaning that they averaged around 18 kilometers of travel per day, which is slow and indicative of poor trail conditions. Stewart turned St. Cyr over to the NWMP detachment in Dawson, then in true Canadian style he went looking for the hockey rink.

The Trial at Dawson

The trial of George St. Cyr got some newspaper coverage, but it was overshadowed by other news happenings in Dawson, particularly the ongoing story of the investigation and pending murder trial of George O’Brien. There was also the killing of Pearl Mitchell in October by her purported husband James Slorah in a room above a saloon and the disappearance and search for Dr. Joseph Bettinger along the Yukon River winter trail in December.

In addition to these stories, the upcoming murder trial of St. Cyr focussed on him because of his family connections and being known in Dawson. This meant that little attention was given to James Davis, the undeserving victim of murder, but there was likely little known about him to write about.

In the days leading up to the trial, one newspaper reported that George St. Cyr was in good spirits and expected to show that the shooting was in self-defence. The paper also stated that because of his good character and family reputation, public sympathy would be with him. On January 4, 1901, St. Cyr was taken before the court, where he pleaded not guilty to the murder of James Davis and elected to be tried by a jury. His attorneys, George Black and C.M. Woodworth, requested more time to gather evidence, and the trial eventually began on February 4 and wrapped up three days later.

William Clethero was the first witness to testify and the primary one because of his history with St. Cyr and Davis and being near the shooting when it occurred. Both he and St. Cyr, who testified later in his own defense, described the events more or less as they had related them at the coroner’s inquest in Hootalinqua. There were a few inconsistencies between them, but the only issue that St. Cyr particularly refuted was Clethero’s testimony about the details of the physical altercation they had in the evening their partnership ended.

When he took the stand in his own defence, George St. Cyr was described by the Dawson newspaper as under medium height but strongly built, 45-50 years old (he was actually around a dozen years younger than this), bald with grey hair and mustache, and speaking with a slight German accent (being from Quebec, this would more likely have been French). The newspaper said he appeared to be nervous and spoke rapidly when answering questions.

NWMP Cst. Gardiner testified at the trial because he had taken the first statement from St. Cyr at Hootalinqua, but also because he had sold St. Cyr the rifle that had been used to kill Davis. St. Cyr’s attorneys asked him some questions that explored the possibility of the rifle being fired by the hammer being drawn part way back and released, without it being actually cocked and the trigger intentionally pulled. Gardiner responded that he had no experience in that regard, but he would not like to stand in front of the rifle to test that theory.

There were other references at both the inquest and the trial about things that could have caused the discharge of the gun, such as a sudden jarring of it or folds in St. Cyr’s clothes that pulled the trigger. St. Cyr also said he had his mitts on at the time, implying that he couldn’t have pulled the trigger with his finger.

A number of witnesses were called to testify to George St. Cyr’s character, with the result a somewhat mixed bag, some contradictory, but generally in his favor. Jean Coté, a Dominion land surveyor, said that he worked with St. Cyr on a surveying trip in 1894-95, where he had a good reputation and got along well with other party members. He was a nervous man, but “not of a melancholy or brooding nature”, and was “frank and jolly, and very talkative”.

Joseph Primeau, the camp cook and woodcutter who had lived with St. Cyr for a time in Hootalinqua, said St. Cyr was nervous and excitable at times, but his reputation was good. He said he couldn’t shed any light on St. Cyr’s relationships with others. A man named John Hale said he had met St. Cyr a few years previously in Victoria and knew him for about a year, and that he had a good reputation.

The most scathing comments came from Commissioner William Ogilvie, who testified that he met St. Cyr in the spring of 1894 when he was working on a survey party for the international boundary under Ogilvie’s direction. Ogilvie said that St. Cyr had a reputation of being a “crank” and “intensely disagreeable in camp, resenting things said to him, seeming to brood over them for days afterwards”.

During this part of the trial related to St. Cyr’s character and reputation, there was a discussion about insanity. While it appears to have been raised by Black, St. Cyr’s attorney, he did not want to show insanity as a defence.

In the trial summation, the Crown prosecutor reviewed the evidence and advanced his view that the accidental shooting claimed by St. Cyr was improbable, and used a rifle to demonstrate. This was followed by Justice Dugas’s instructions to the jury, and also his expressed opinion that St. Cyr, “in the telling of his story, impressed him very favorably”.

The jury deliberated for about 1½ hours in the evening of February 6, returning a verdict of guilty with a recommendation for mercy. This came as a surprise, as most people following the trial were expecting not guilty, or at least a reduction to manslaughter. There was no obvious reaction from George St. Cyr.

On the following morning of February 7, 1901, Justice Dugas sentenced St. Cyr to death. This was another surprise, but Dugas stated that the guilty verdict for murder left him no alternative. He asked St. Cyr if he had anything to say, to which St. Cyr replied that the gun went off by accident. Dugas said that was information the court had already heard, and sentenced St. Cyr to hang on June 7. George Black made an immediate formal motion to suspend the sentence for an appeal to be undertaken “on the grounds that the verdict of the jury was against the weight of evidence”.

The Aftermath

James Davis‘s Burial

After Cpl. Stewart and Cpl. Richardson retrieved James Davis’s body from the murder site and stored it in a cache at his cabin for the night, they took it back to Hootalinqua, likely the next day. This would have involved one or more of poling, rowing, and lining their boat (the latter meaning pulling with a rope) against the Yukon River current with the body of a large man in it. Once at Hootalinqua, they would have had to preserve the body as well as possible for a coroner’s jury to be able to view it. They would not have known when that would occur, and as it turned out it would not happen for another 11 days.

James Davis was buried in the Hootalinqua cemetery, located on an open ridge about a quarter of a mile to the north of the settlement. It was carried out by some local men who were paid $30 for the work, which in late November or early December would have involved keeping a fire going to thaw the ground for digging the grave.

(Yukon Archives, Geological Survey of Canada fonds 90-36, #117 – image has been cropped)

On the 1901 census Mortality page, the line below the entry for James Davis shows that a Fred Johnson, also in his 30s, died of natural causes the month before Davis. Johnson was buried in the Hootalinqua cemetery and in 1972 his grave marker was still legible. There is a good chance that a grave close to Johnson’s that either never had a marker or it was gone or illegible by 1972 is Davis’s burial site.

(Yukon Archives, Yukon Waterway Sites fonds Acc. 88/18, #164 (1-17) – image has been cropped)

At some point the Public Administrator advised James Davis’s family in Walla Walla, Washington by telegraph or letter of his death and burial, adding them to the list of the many families who saw one of their own go off to the Klondike and not return. In July 1901, James’s mother Caroline Davis wrote back about the possibility of her son’s remains being sent back home and was informed that the cost would be $250 to $300 to have the body exhumed and shipped to Vancouver, plus the cost of its transport to Walla Walla. In a further letter in November 1901 she said that they were still undecided about this, but in the end it did not happen.

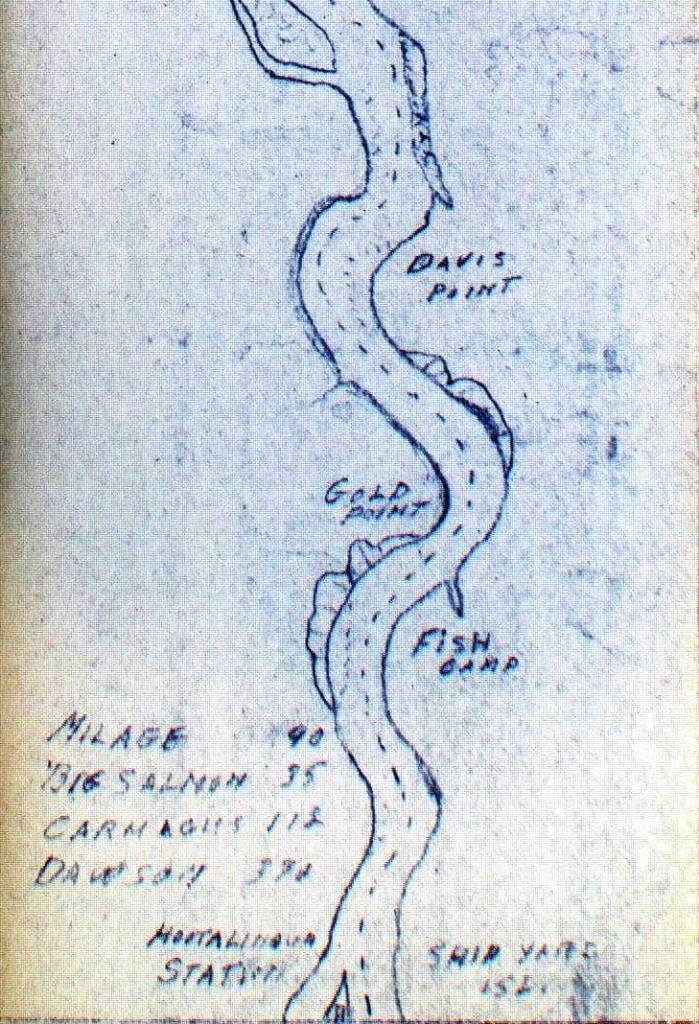

A legacy of James Davis’s life is the unofficial name of Davis Point on the Yukon River, where his cabin was located and near the site of his tragic death. It appears on a river chart sketched by long-time steamboat pilot Emil Forrest, which I became aware of thanks to Mike and Jocelyn Rourke. The 2022 edition of the Rourkes’ Yukon River guidebook contains a summary of Davis’s murder and George St. Cyr’s trial and sentence along with a map label for Davis Point.

(Yukon Archives, Emil Forrest fonds, Map H-720)

George St. Cyr, Inmate

George St. Cyr was an inmate from the time of his arrest for the murder of James Davis until his death. Three days after he was found guilty of murder in February 1901 and sentenced to hang in June, he attempted to commit suicide twice in the same day by jumping off of his bunk onto his head to break his neck. The reason was apparently because of the shame he had brought onto his family, but the only results were severe bruising and a special guard placed in his cell day and night. One newspaper reported that George’s brother Arthur never came to assist or support him during or after the trial, even though he was in the country surveying the Yukon-BC border that year.

In March, when St. Cyr was serving the few months he had left until his scheduled execution date, Justice Dugas went to bat for him in a letter to the federal Minister of Justice in Ottawa. Dugas included a report summarizing the details of the murder case, along with his opinion that St. Cyr’s “evidence was such to impress strongly that he was telling the truth”. He pointed out that St. Cyr had surrendered immediately, had not gone near the only witness (Clethero), and had given consistent accounts of the shooting. Dugas said these factors left some doubt in his mind about St. Cyr’s guilt and he had communicated this to the jury, to no effect, but he said he wanted to support the jury’s recommendation for mercy in St. Cyr’s sentence.

The result of Dugas’s appeal was that on March 18, 1901 St. Cyr’s death sentence was commuted to imprisonment for life in the guard room of the NWMP in Dawson. The Order-in-Council for the commutation was signed by the Governor General Lord Minto, who had passed through the Hootalinqua on a trip to the Klondike the previous August, just three months before the murder. A telegram pronouncing the reduced sentence was read to St. Cyr, who listened intently and had no reaction other than nodding and was taken back to his cell.

The newspaper reported that St. Cyr’s appearance had changed in the two and a half months since his trial, from being clean-shaven with neatly trimmed hair and “a glowing cheek”, to a gray-bearded old-looking man. The paper also made the observation that St. Cyr’s new sentence meant his life would change from sitting and waiting for his meals to toiling in the prison yard for the rest of his life.

St. Cyr’s time at the prison in Dawson was only to last to the end of the year, however. In the intervening months he had shown signs of what was deemed to be insanity and had become increasingly violent, so it was decided to transfer him to an asylum in New Westminster, BC. In late December and early January he was taken by dog teams in relays to Whitehorse, then on the White Pass train to Skagway, and by steamship to Vancouver, where he and his escort arrived on January 5, 1902. The escort was NWMP Cst. Robb, and St. Cyr was said to have been “only at times giving the officer any difficulty”.

St. Cyr’s tenure at New Westminster lasted less than a year, similar to his time in the Dawson jail. By December 1902 he was pronounced sane and was transferred to the Kingston penitentiary in Ontario to serve out the rest of his life sentence. At some point in his time at Kingston, St. Cyr was transferred to an asylum at Guelph, Ontario, presumably because he was deemed to have lost his sanity again.

The details of this transfer to a Guelph asylum are not known, but it had happened by 1923 because St. Cyr was there when he became entitled to an inheritance from the death of his brother Arthur in Mexico. The other heirs (his siblings and their children) contested that because George was insane, the $14,000 left to him should be distributed amongst them. The case went to the Supreme Court of Ontario, which ruled that his share should be left in the hands of the public trustee because St. Cyr might someday recover his sanity and be capable of administering his own estate. That is the last record I have found about George St. Cyr, and have not determined when he died and where he is buried. He does not show up in a search of the 1931 Canada census.

William Clethero‘s Yukon Life

Following James Davis’s death, his partner William Clethero provided a listing of what was in the cabin they had shared, such as tools, cooking equipment and utensils, and food provisions. He purchased everything except personal items such as clothing and bedding that had belonged to Davis. After the trial in Dawson, Clethero returned to the Hootalinqua area and resumed his previous life there, presumably living in the same cabin.

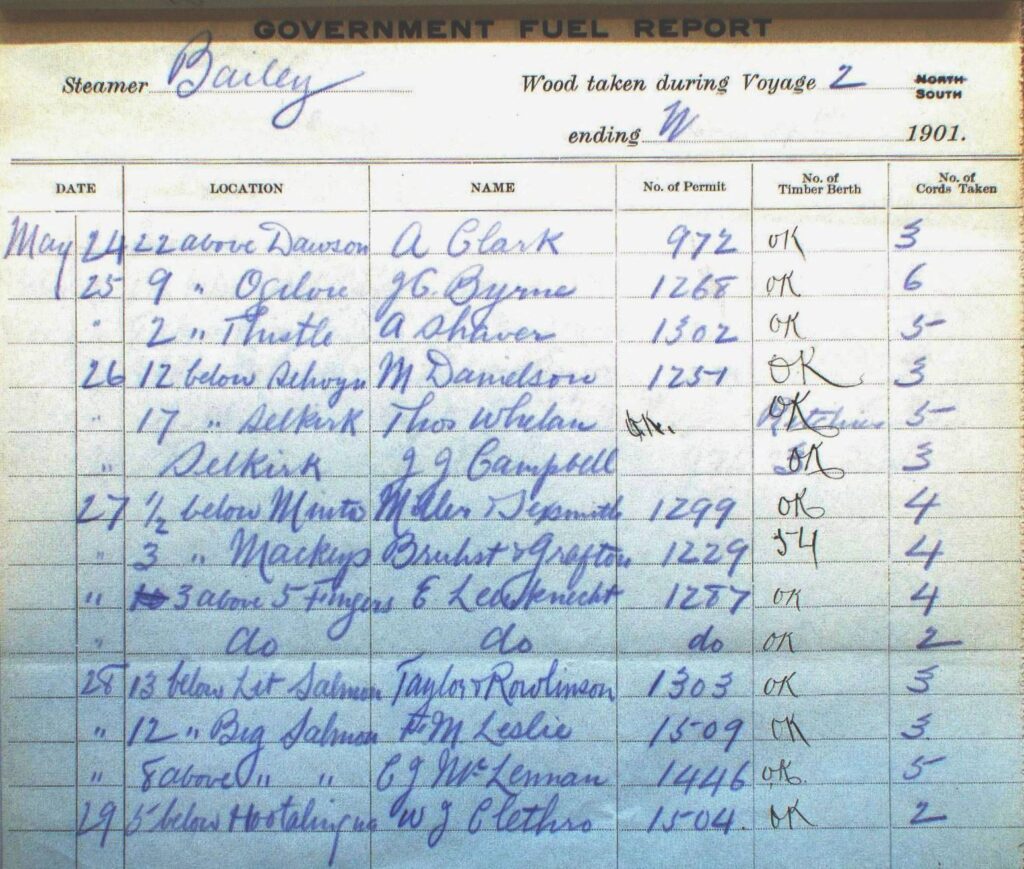

After the trial in Dawson, William Clethero resumed his previous life in the Hootalinqua area. A few months afterward when the ice went out of the Yukon River in May 1901, he sold steamboat fuelwood from a location eight kilometers north of Hootalinqua. This would have been the wood that he and Davis, and perhaps also St. Cyr, had cut the previous year. He had a horse to assist him in his work, perhaps the same one that carried the body of James Davis down off the hill from where he was killed.

(Yukon Archives, GOV 1683, file 53)

Clethero went on to live in the Yukon for more than 50 years, raising a family and engaging in a number of endeavors including mining in the Livingstone Creek area and the Whitehorse copper mines, working on big game hunts, and working in the trading post business at Champagne. William Clethero died in 1953, leaving many descendants in the Yukon, and is buried in the Pioneer Cemetery in Whitehorse.

The Properties

James Davis’s estate consisted of very little after various expenses were paid out, such as his burial and the amount owing on his land and the survey. The Public Administrator put Davis’s Lot 8, Group 4 up for sale in hopes it would give a boost to the estate that could be passed along to his family. His mother wrote three more letters, the last almost two years after her son’s death, asking about the sale of his land, but in October 1902 she was advised by the Public Administrator that they had been unable to dispose of it.

Lots 10 and 11, Group 4 that were surveyed for George St. Cyr in July 1900 were not registered in the Yukon Government’s Land Titles Office, so they never went to title and reverted to the Crown. After James Davis’s death, Lot 8 that had been surveyed for him was registered in the name of the Yukon Public Administrator, evidently as part of settling Davis’s estate, but is also now in the name of the Crown. The three lots sit out on the landscape as surveyed land parcels that serve no current purpose.

Visiting the Sites

In July 2022 Ron Chambers and I visited the area near Hootalinqua where George St. Cyr, James Davis and William Clethero lived and worked in 1900. The survey plans for the lots enabled the locations of the cabin sites to be approximated and searched for to see if evidence of them could be found. It was also to gain a better understanding of the geography and setting where these woodcutters worked and one of them died.

James Davis’s cabin site was in a somewhat more prominent place than St. Cyr’s, located not far off the river on a small rounded point. There was not much to see there, but a sizable hole in the ground was likely a cellar under his cabin for keeping things cool in the summer and some protection from freezing in the winter. Encircling the hole was a berm of dirt that would have come from the roof of the cabin. The building had probably been removed for rebuilding elsewhere or for firewood, but various pieces of rotting lumber, some with nails in them, were scattered around the site as more evidence of occupation there.

(Gord Allison photo)

A kilometer downstream (north) from Davis’s site was where St. Cyr’s cabin location was found, farther back from the river and close to a hillside rising not far behind it. There was even less evidence than at Davis’s cabin site, primarily in the form of tin cans and some bottles lying around. The site showed that the abnormally high water of the Yukon River earlier in the summer had flooded over the site, scattering much of the human evidence around and depositing a layer of silt across the area. An exact determination of where the cabin sat was difficult to ascertain.

(Gord Allison photo)

Ending

A seemingly innocuous look at survey plans from 1900 led to researching the murder of James Davis and visiting the area along the Yukon River north of Hootalinqua where he and two other men lived and worked. The research revealed that Davis met his untimely and senseless death from a number of combined factors, including: men working in an isolated bush setting but in relatively close proximity to each other; no identifiable boundaries on the ground to mark the limits of their timber rights; a history of increasing tensions and bad feelings; and perhaps a developing mental health issue referred to at the time as ‘insanity’ or ‘lunacy’.

The dedication of the North-West Mounted Police in pursuing justice for James Davis was commendable, especially considering the circumstances. From the start of the investigation of the shooting near Hootalinqua to the handing down of the murder sentence 550 kilometers away in Dawson took about two and a half months. Much of the force’s work required considerable physical effort to travel on the land and water at a difficult time of year.

The murder trial of George St. Cyr was relatively well covered in the Dawson newspaper, but it gave no glimpse into the life or background of the victim. The sad tale of James Davis’s death might have garnered more attention and sympathy had it not taken place in the shadow of the more sensational O’Brien murder case that gripped the country for a year and a half.

George St. Cyr died in either a prison or an asylum as a convicted murderer. His sentence may have been justified or he may have been the second victim of a confrontation that went terribly wrong. The shooting death of James Davis may not have been his intended outcome, but it happened because he chose to bring a loaded rifle to a conversation with Davis and to keep it pointed at his chest.

John and Caroline Davis in Walla Walla, Washington saw their eldest son set off on an adventure and possibly a new life in the Yukon, but would never see him again. For James Davis, his final resting place is on a peaceful ridge overlooking the beautiful Yukon River valley he had ventured to and acquired some land where he may have envisioned his future.

Link to related article: Finley Beaton, Yukon River Woodcutter

Updated 18 April 2024