The Kluane Wagon Road – part 3

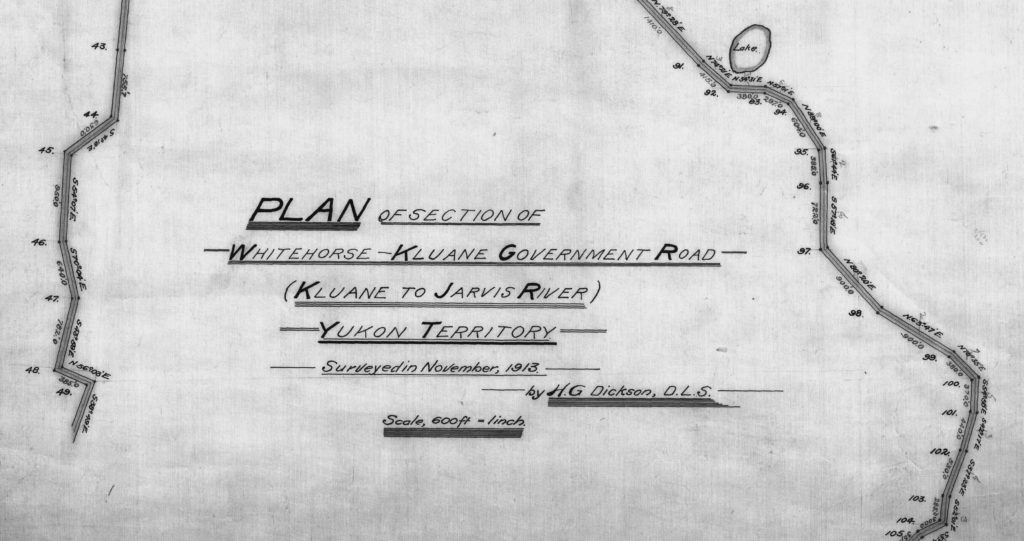

The Legal Survey of the Kluane Wagon Road

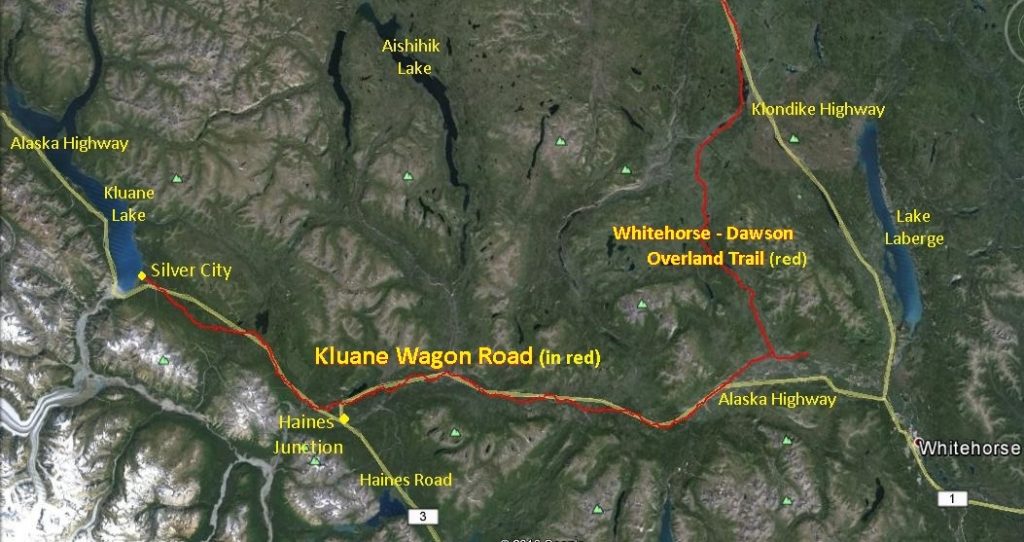

The Kluane Wagon Road (KWR) appears to have had only one route from its start at the Whitehorse-Dawson Overland Trail to Marshall Creek, about 10 miles east of present-day Haines Junction. From that point, there were branches for summer and winter use, others to access the gold creeks north of Kloo Lake, and an eventual winter route to Cultus Bay on Kluane Lake. These old roads are all loosely referred to as ‘Kluane Wagon Road’ by locals who come across them on the landscape.

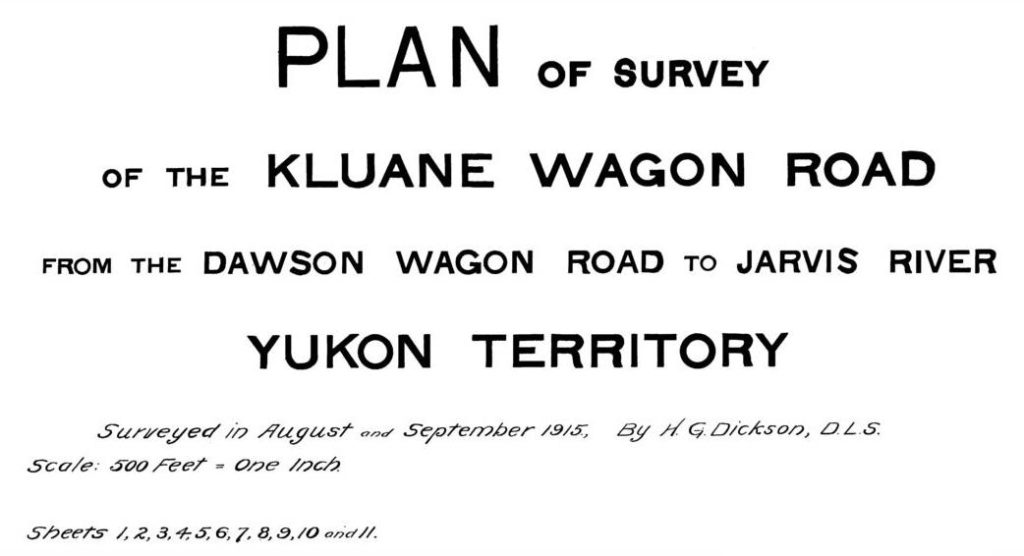

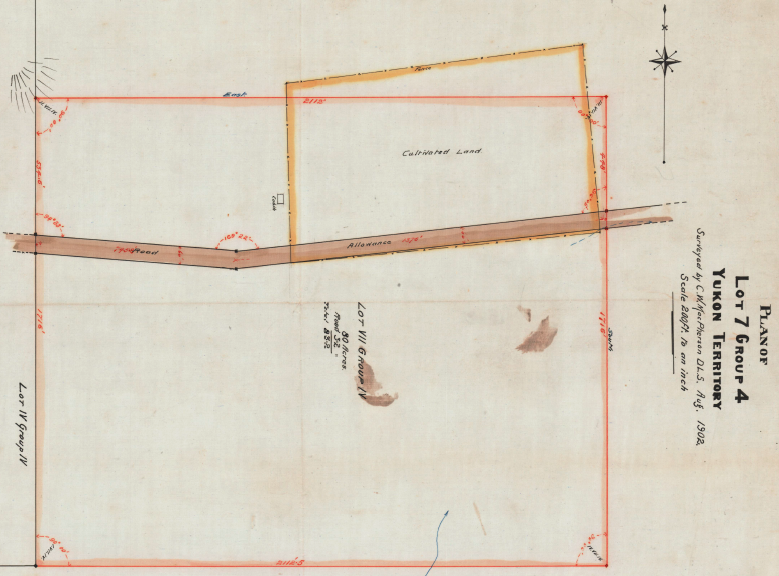

One route, however, can justifiably claim this name by virtue of the legal survey of it that was carried out in two projects in 1913 and 1915 by Henry G. Dickson. He surveyed the 22.5-mile section from Silver City (then called Kluane) southeastward to Jarvis River in eight days in November 1913. Over 43 days in August and September 1915, he completed the project by surveying the 100 miles from the Overland Trail westward to the Jarvis River, joining up with the 1913 survey.

(Canada Lands Survey Records #34661)

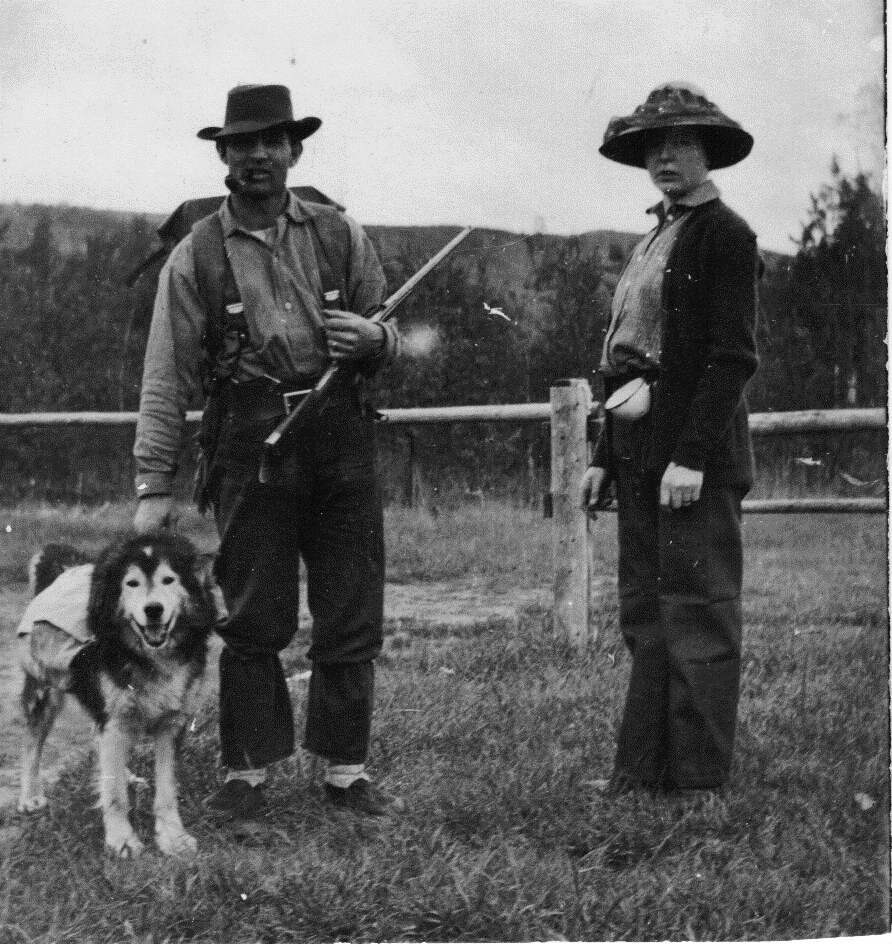

The reason for surveying the KWR is not clear, but it may have been a desire to increase the relatively sparse legal survey fabric of the region. Perhaps it was viewed that the surveyor Dickson, who was working in the area in the summer of 1913, should be prevailed upon to also survey the KWR at a time when the region was seeing increased prominence with the new big game hunting industry. In addition, the KWR was experiencing a spike in traffic in 1913 with a new gold rush to the Chisana area of Alaska just across the Yukon border.

The contract made with Dickson on July 20, 1915 for the second survey project was not viewed favorably by Commissioner George Black, as it was evidently done without consultation with him. The Dawson-based Black complained that the survey “…work is not pressing, and is not particularly important, and the Government needs money so much for vital matters …”.

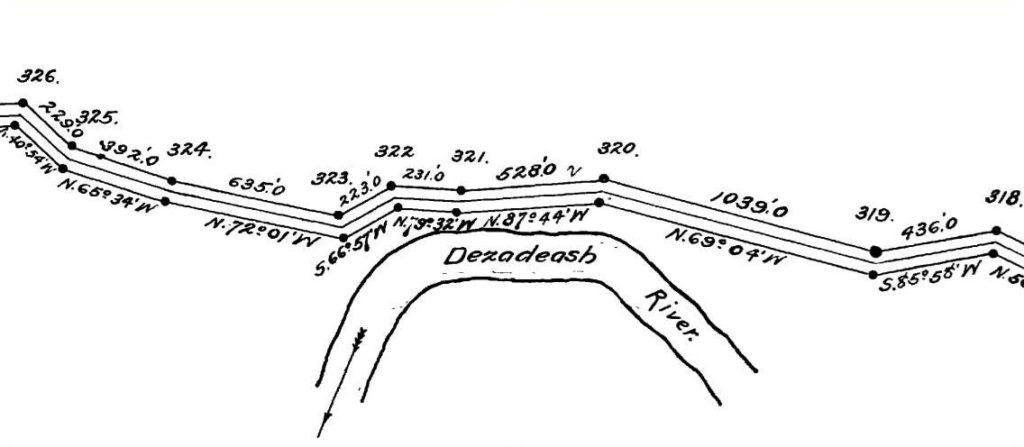

These survey projects defined the main route that was being used at the time and therefore had to follow all its twists and turns. A 66-foot right-of-way was marked out by posts placed on either side of the road at each deflection (curve), with the distance and bearing measured between the pairs of posts. Because of the crooked nature of the road, the survey required a total of 1,908 posts (954 pairs) to mark the route of the KWR. An example of a section of Dickson’s survey plan is provided below:

(Canada Lands Survey Records #34683)

The pairs of survey posts were numbered sequentially from the beginning of the survey projects, from 0 to 151 for the 1913 survey and from 0 to 801 for the 1915 survey. These numbers appeared on the survey plans, but not on the posts.

The vast majority of the survey posts were wooden, but iron posts were placed at important locations, such as the start and end of the road and most roadhouse locations. In addition, several of the wooden posts and all of the iron posts were placed in either a stone mound or in a mound made of dirt from four surrounding pits. These methods were used to make periodic post locations more visible and to remain as evidence long after the wooden posts had rotted away.

(Gord Allison photo)

(Gord Allison photo)

After the survey on the ground was completed, Dickson (or a draftsman) then had to make paper survey plans from his field information. This appears to have been a laborious process with the drafting technology that was available at that time. The 1915 plan is on 11 sheets of two-foot wide paper and appears to be hand-drawn, with the original in color. It was done at a scale of 1 inch = 500 feet (or 1:6,000), meaning that one inch on the plan represents 500 feet (6,000 inches) on the ground. To plot the 99.5 miles of the 1915 survey, about 80 linear feet of paper was required for the 11 sheets that make up the plan.

Retracing the Kluane Wagon Road

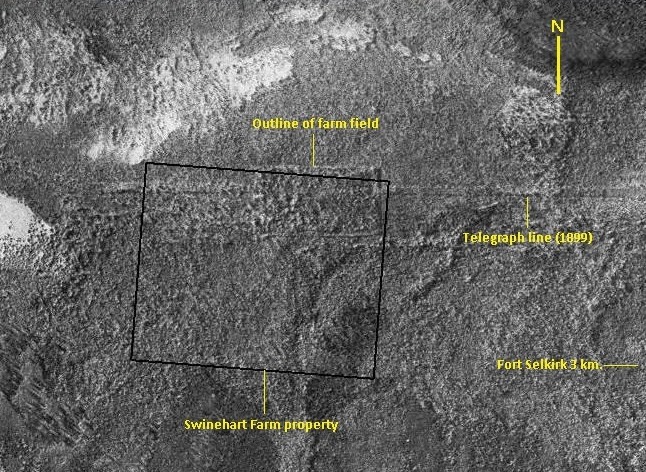

Dickson’s large survey plan sheets show the road alignment and the survey posts with the distances and bearings between them, but there is no reference to their location on the landscape. A number of crossings of named creeks and rivers are shown, but it’s not evident where along the creek or river the crossings are. The only places that indicate the location of the KWR is where it passes through Champagne and Canyon Creek, two localities that had previously surveyed properties, and where it terminates at Silver City.

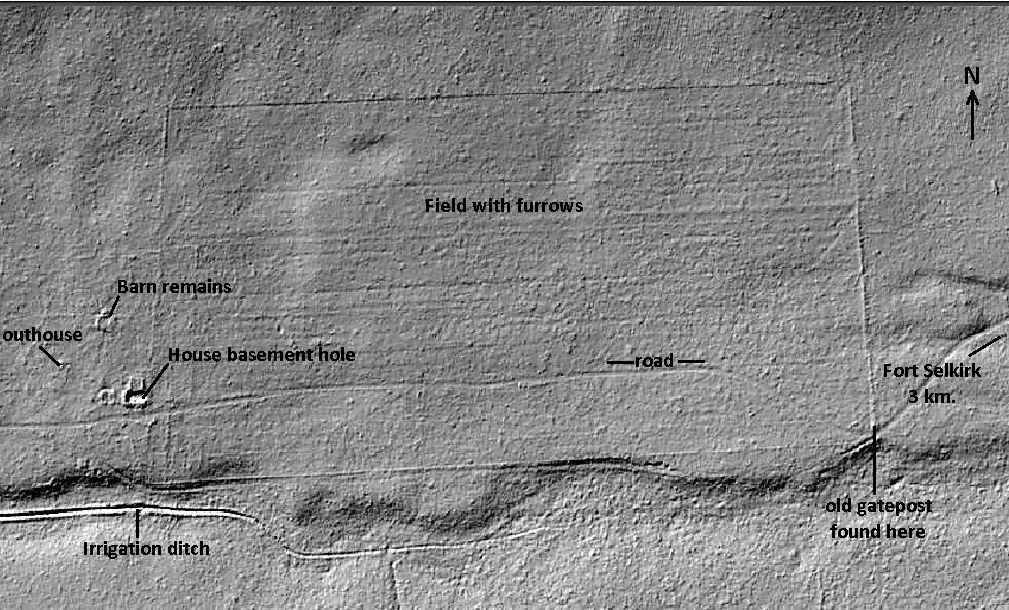

To determine the location of the surveyed KWR on the land, my only option was to try to match up shapes of survey sections with similar shapes of old tracks that still showed up on available air photos. This was a very painstaking process, but it was fairly successful where the road was still visible on the air photos. This gave me the information needed to start looking for the survey posts.

I later found out that the KWR had already been mapped using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) technology of Dickson’s survey. Knowing about this would have saved me a lot of the laborious air photo work. My survey post location information has since shown that there is some inaccuracy in this GIS mapping of the KWR.

The first post I found was by sheer luck while out doing other work a few miles west of Haines Junction. I spotted a squared wooden post with about 4-inch sides and two feet high, with the top beginning to rot away. I was only certain it had to be a KWR post when I saw a faint ‘R’ (for ‘road’) carved sideways near the top on the side of the post facing the road.

(Gord Allison photo)

My wife Roberta and I soon started purposely looking for posts and the first one was found, fittingly by her, a couple of miles north of Haines Junction. We found several posts in that area and then the search expanded from there. Other people, particularly Ron Chambers and my son Neal, began accompanying me on search trips for posts and we eventually covered almost all of the wagon road.

I have calculated that a little less than half of the surveyed KWR route remains relatively undisturbed, and therefore a corresponding amount of the survey posts (about 850 of the 1,908 originally placed) could potentially still exist. To date I have travelled all but a couple of miles of the KWR and have found over 230 posts, two of them iron and the rest wooden or the pits and mounds that marked them. This represents the locating of a little more than 1/4 of the potential remaining posts.

The wooden posts are in varying conditions, with some still standing fairly solidly, some leaning or ready to fall, and others laying on the surface. Many of the latter are in quite rotten condition, some of them barely recognizable as survey posts. Those that could not be located have presumably rotted away, were burned by forest fires, or were not found for some other reason.

The located posts are the proof of the KWR’s location and there are enough of them remaining to confirm the route. GPS co-ordinates taken of the posts will preserve this locational information after they have disappeared from the land.

The KWR is located on lands with a variety of ownership or jurisdictions. About 30% is on (and obliterated by) old and new sections of the Alaska Highway, about 15% is on First Nations’ Settlement Lands, and another 8% is on private property, municipal land, and lands for other uses such as utility easements. The remaining 47% is on vacant Crown land.

The KWR survey no longer appears on maps or on most subsequent legal survey plans of overlapping or adjacent parcels. However, the Surveyor General Branch (the federal agency responsible for legal survey standards and records) advises that the KWR survey still exists as a legal survey and it is technically illegal to remove the survey posts.

End of the Kluane Wagon Road

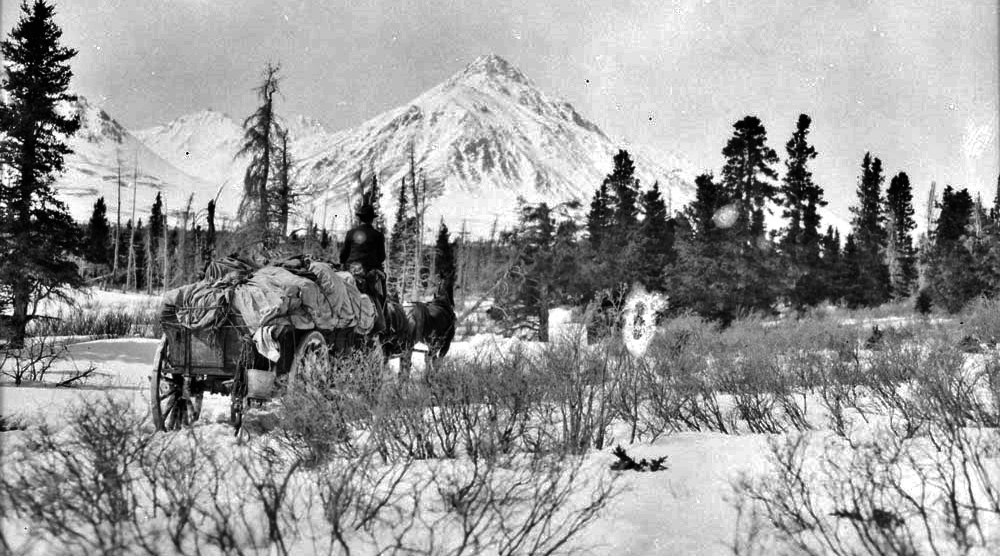

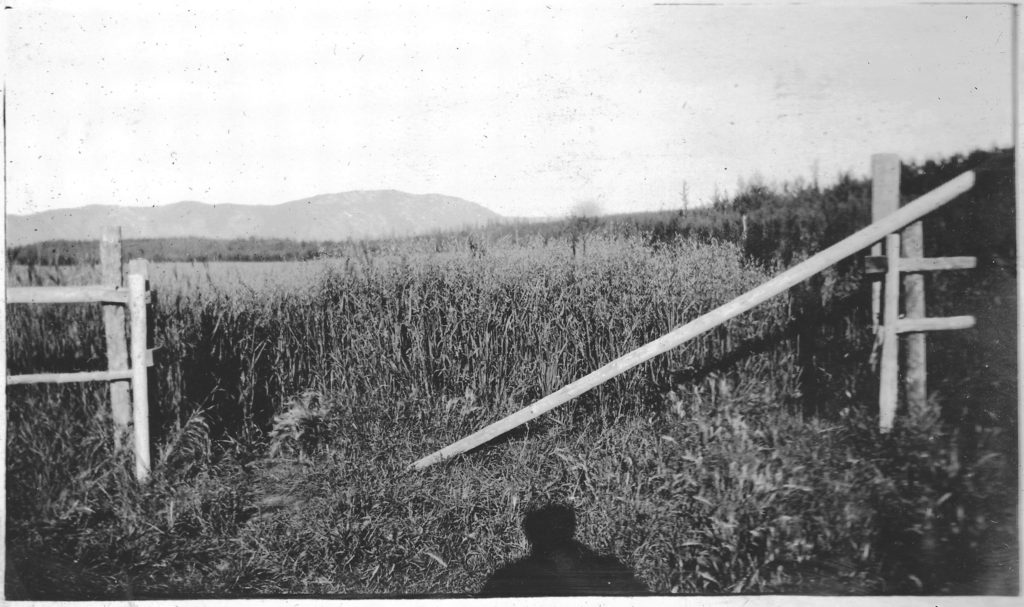

The construction of the Alaska Highway in 1942 changed things drastically and rapidly for the people of the southwest Yukon. It meant the end of travel on the comparatively primitive KWR and the beginning of relatively modern highway travel. While the quicker travel time afforded by the highway was undoubtedly welcomed, perhaps some residents of the area remained nostalgic for a time about their travels and experiences on the KWR.

The KWR’s role as the primary transportation route into the Kluane region for the previous four decades came to an end. Some sections of it were covered partly or totally by the Alaska Highway, particularly the section eastward from Champagne. Other portions have been overtaken by developments such as the Haines Junction airport, the Yukon Energy transmission line, gravel pits and private land dispositions. However, much was also left intact, with some parts used for years afterwards for wood-cutting and other localized activities.

Today the intact sections of the KWR exist in a variety of conditions. Some can be driven by all-terrain vehicle or snowmobile, some can only be traversed on foot, and some are so overgrown that the road is hard to find. Most of the remaining road is seen by very few people, although some sections have occasional recreational use, some is still used for wood-cutting and trapping access, and one section is used for access to mining claims. However, most of these users are likely unaware that they are travelling on what was the KWR.

(©Gord Allison photo)

One section of the KWR that is somewhat well known branches from the Alaska Highway near km 1477, about five miles west of the Takhini River, and heads northeast toward the Little River. This section, much of which was also the initial Alaska Highway route in this area, has provided access for woodcutters, hunters and trappers, recreationists, and, more recently, landowners. A government road sign saying ‘Kluane Wagon Trail’ erected in the summer of 2015 at the junction with the Alaska Highway has likely increased awareness of the KWR in that area.

The Kluane Wagon Road is a historic feature of the Kluane region. Many of the intact portions of it are slowly disappearing into the landscape, as are the survey posts that for over 100 years have marked its existence. It is my hope that the KWR will be recognized as a valuable historic resource and be taken into account in land use activities that may affect it.

(Library & Archives Canada, PA-044618)