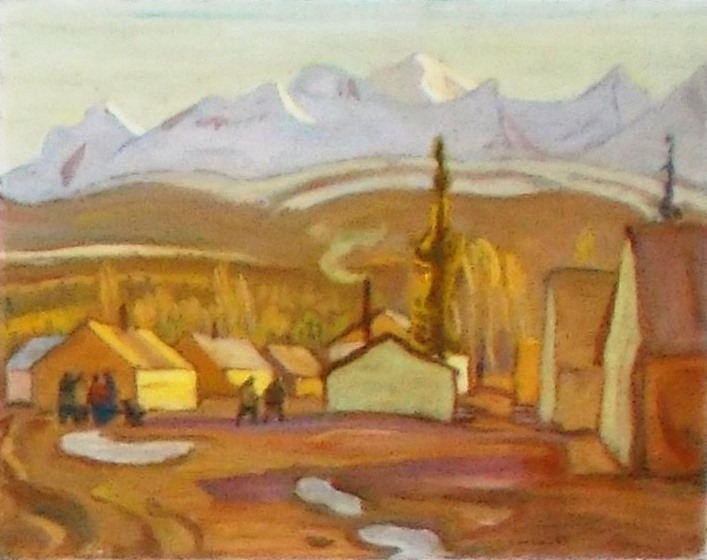

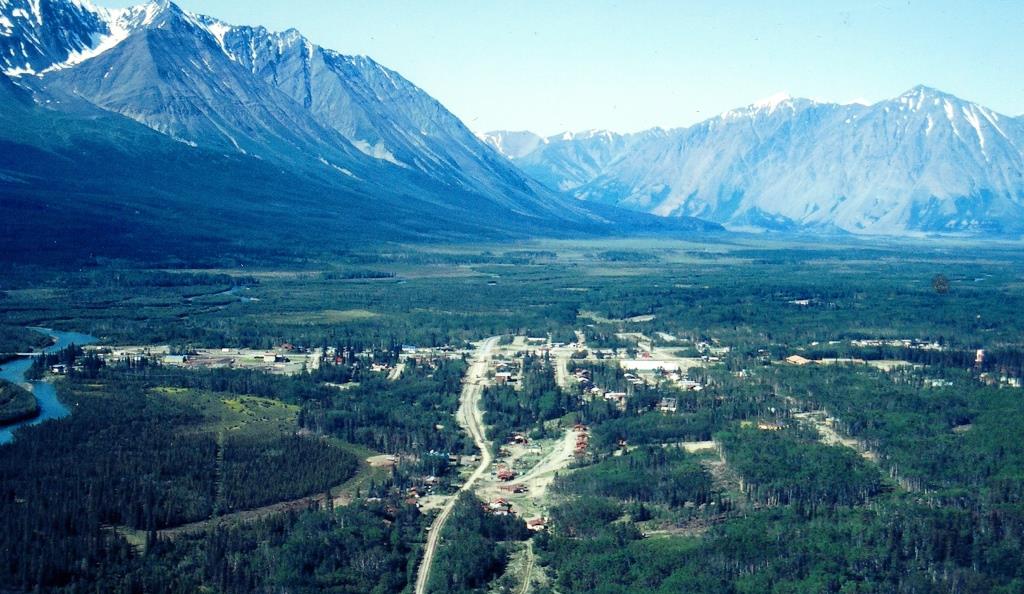

The Beginning of Haines Junction

(Gord Allison photo)

The highway and bridge construction site known as Camp Mile 108 that was established in 1943 beside the Dezadeash River at the junction of the Alaska Highway and Haines Road would gradually evolve to a permanent highway maintenance camp and ultimately a community. This evolution, however, was not assured until July 1946 when restrictions placed on development along the Alaska Highway were lifted and an agreement was made between Canada and the US to maintain the Haines Road. It would take a few more years after that for the Canadian government to implement its process to get land into the hands of people wanting to establish businesses and residences at the site.

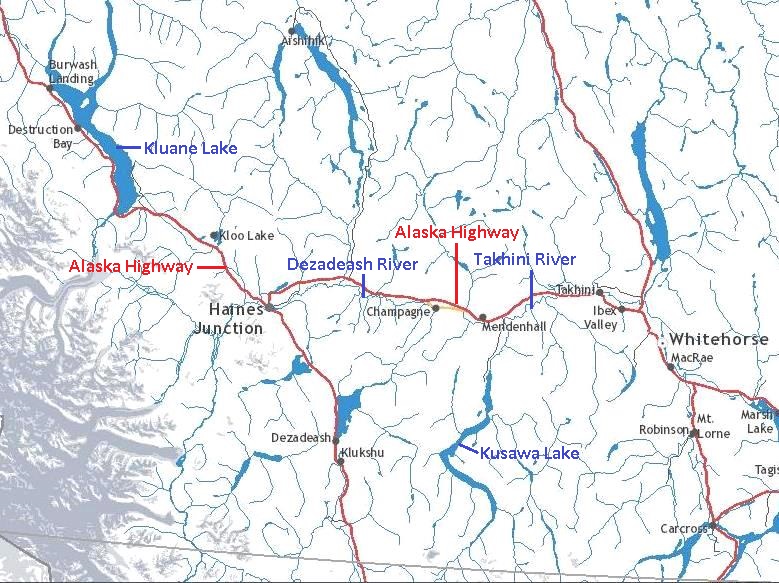

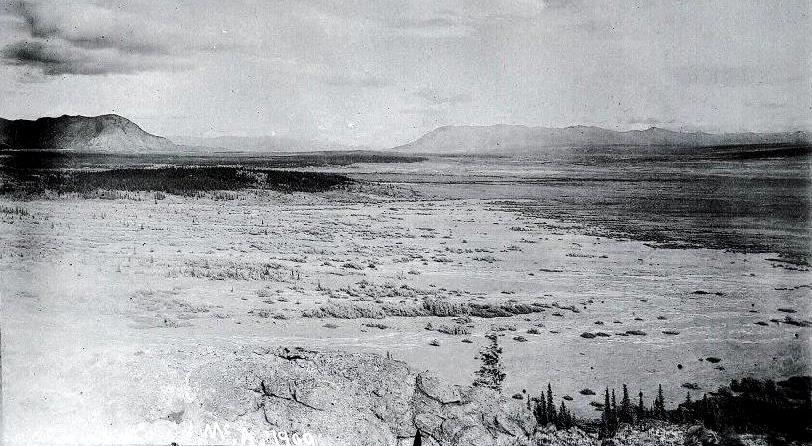

Before the Second World War and the building of the Alaska and Haines Highways, the Canadian and American governments were already interested in setting aside the southwest Yukon and an adjacent area in Alaska for preservation and recreation. For its part in this vision, the Canadian government set aside 10,160 square miles adjacent to the two highways, land that now constitutes Kluane National Park and the Kluane Game Sanctuary.

In 1942 the Canadian government also placed a crown land reserve of one mile on either side of the Alaska Highway that prohibited any land development for townsites, private enterprises, and homesteading until at least after the end of the war. People were therefore not able to stake land at the highway junction immediately after the highways were completed, but had to wait for the prohibition to be lifted. This did not appear to apply to government functions, such as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, Yukon Forest Service, and an Experimental Farm that was established near Haines Junction.

For the first couple of years after the highway construction, the maintenance camp was all that was located at the highway junction. After that other developments started to arrive, beginning with government services and followed by private enterprises, both commercial and residential. This was the beginning of the community to be known first as Mile 1016 and then as Haines Junction, a place that became a home to people over the past 80 years.

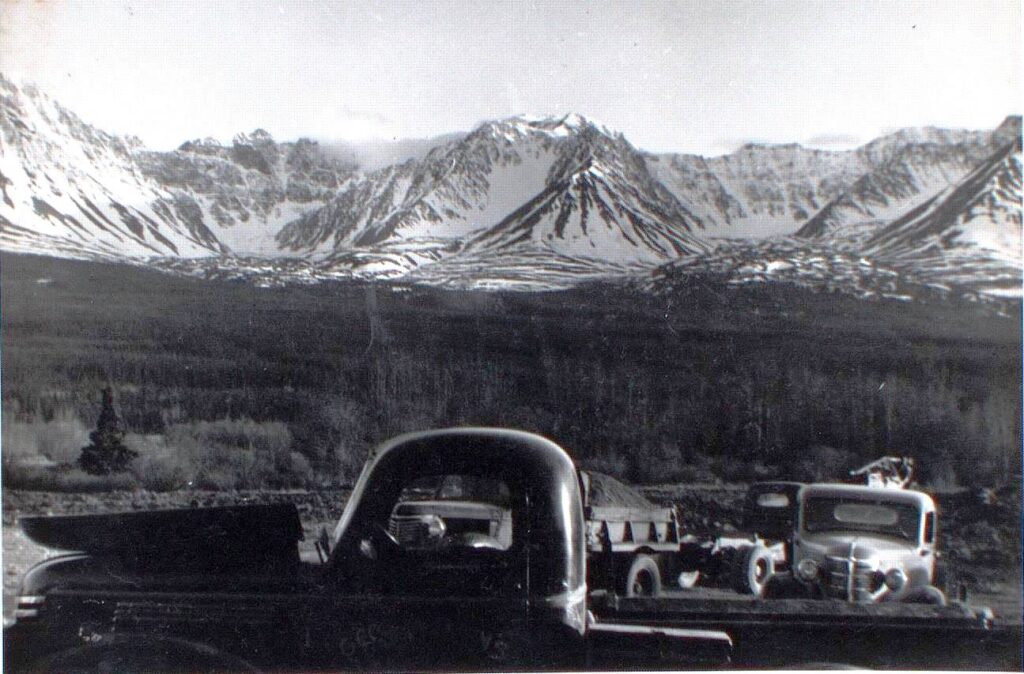

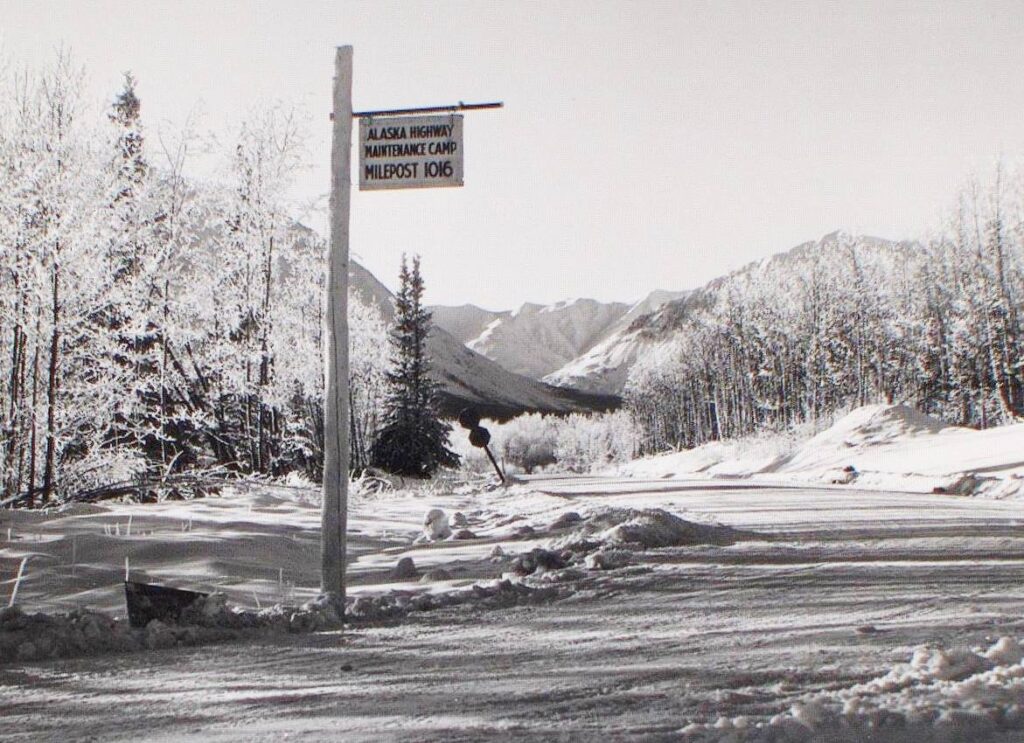

The Junction at Mile 1016 (1944)

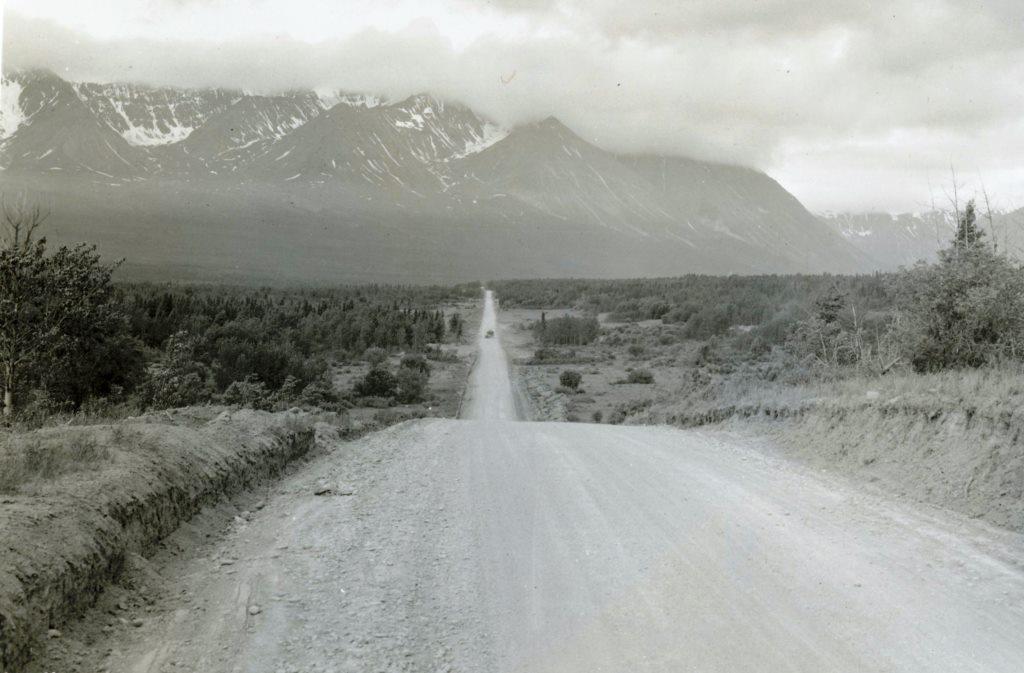

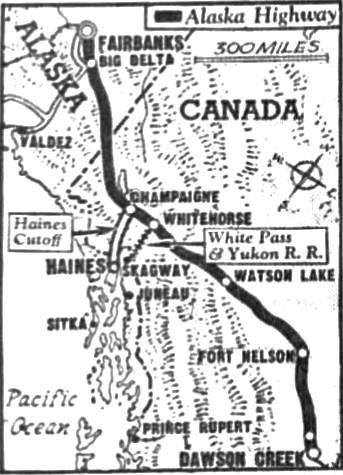

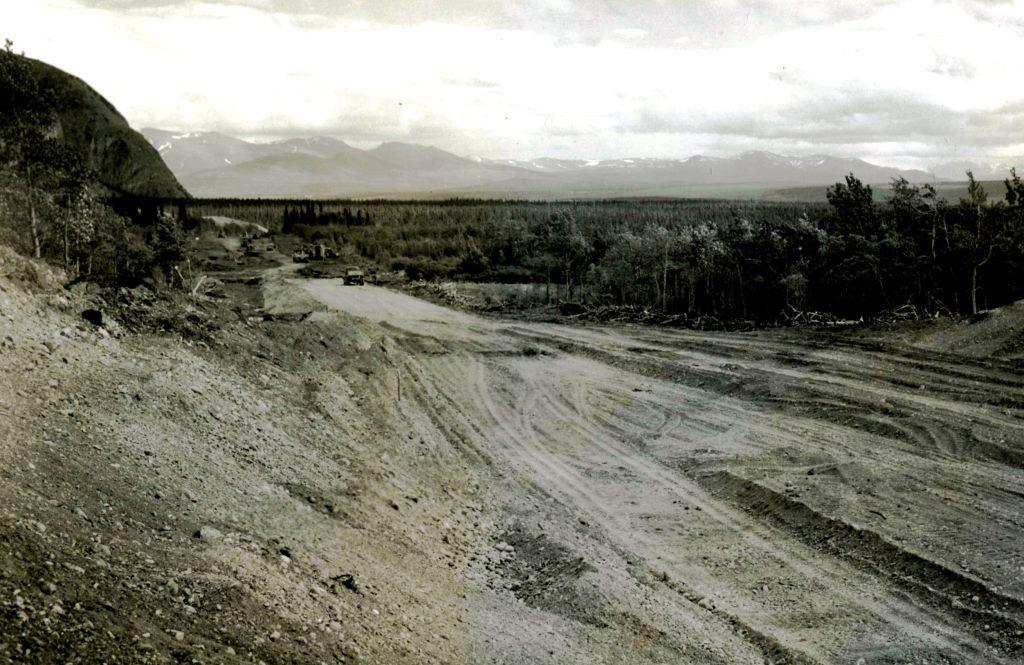

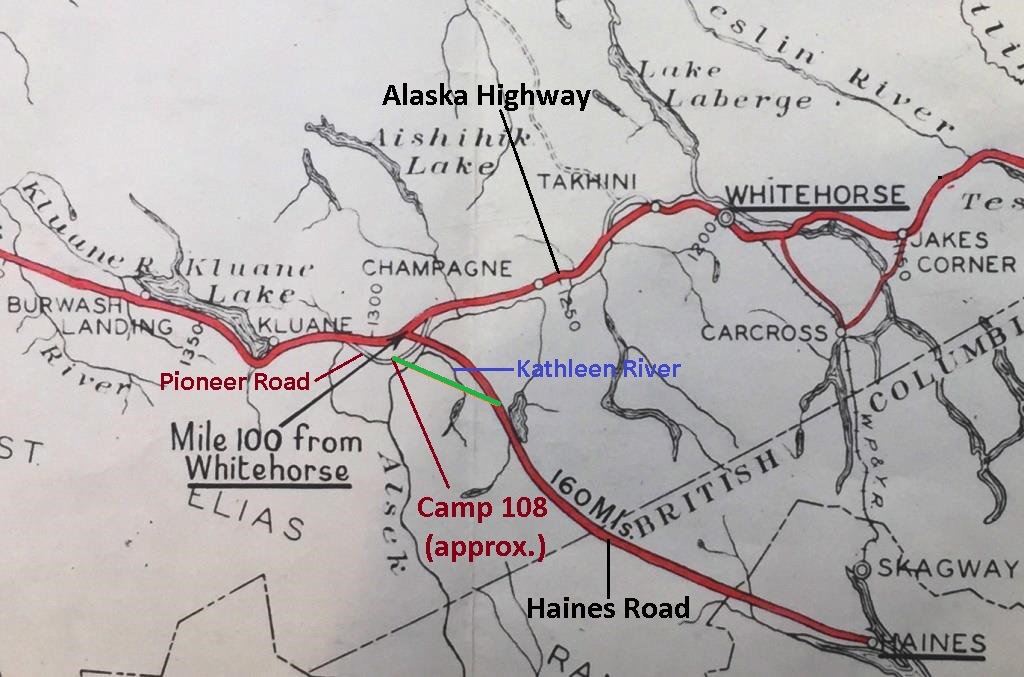

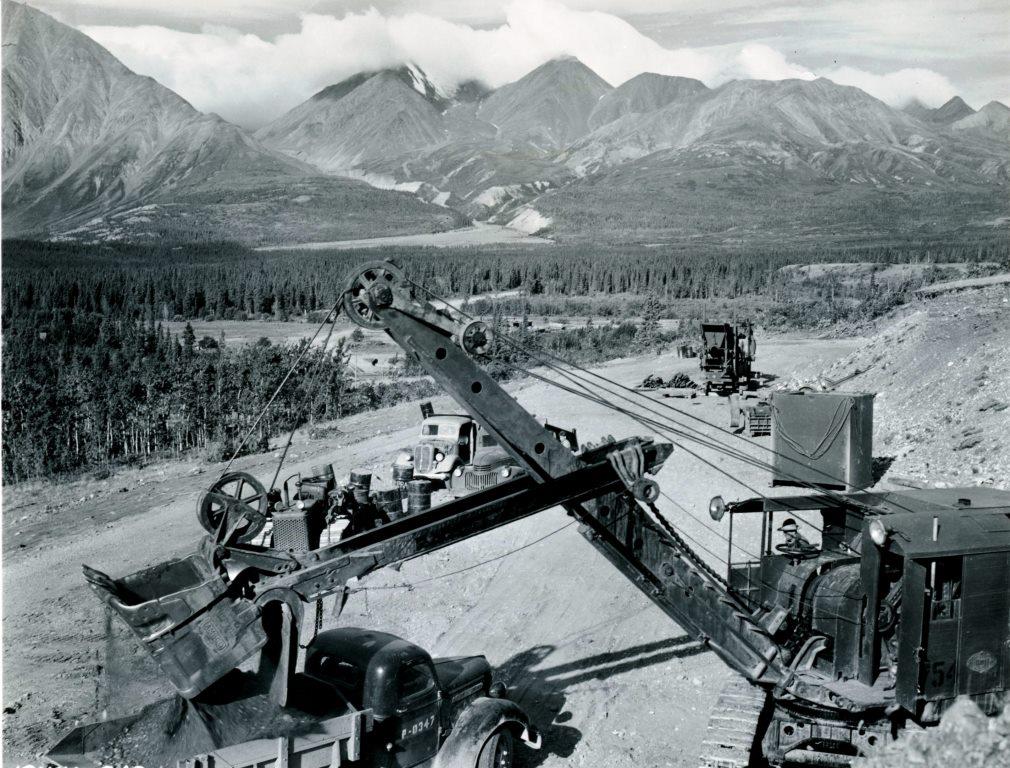

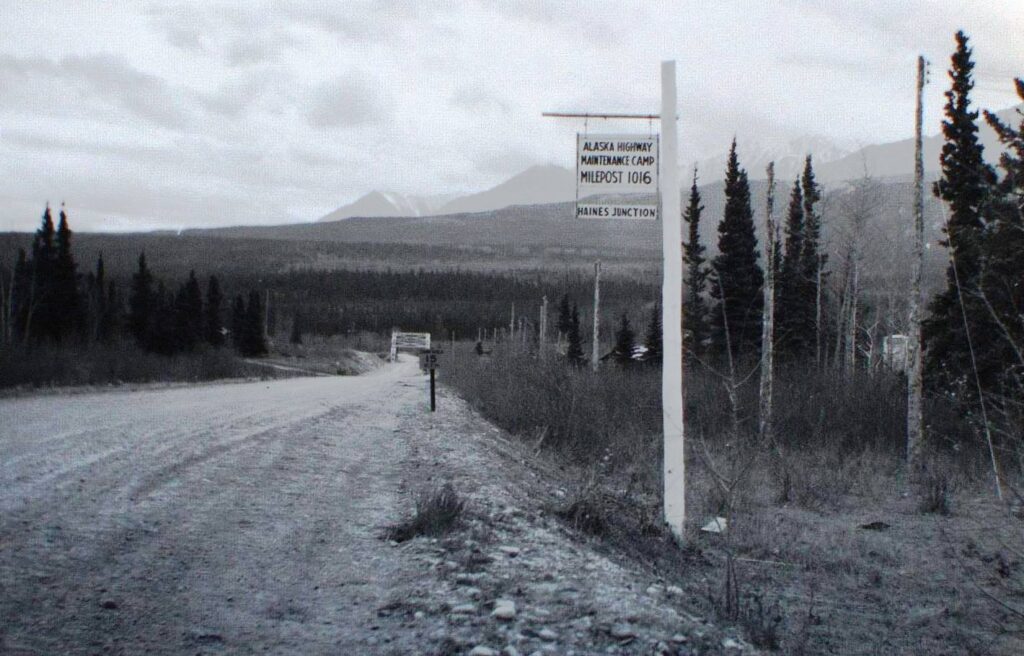

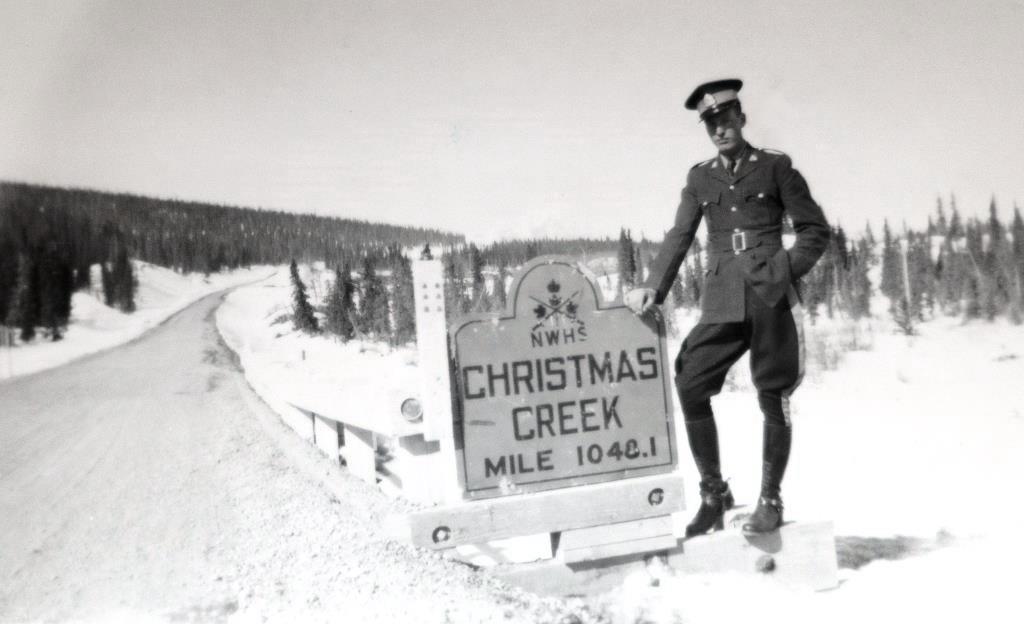

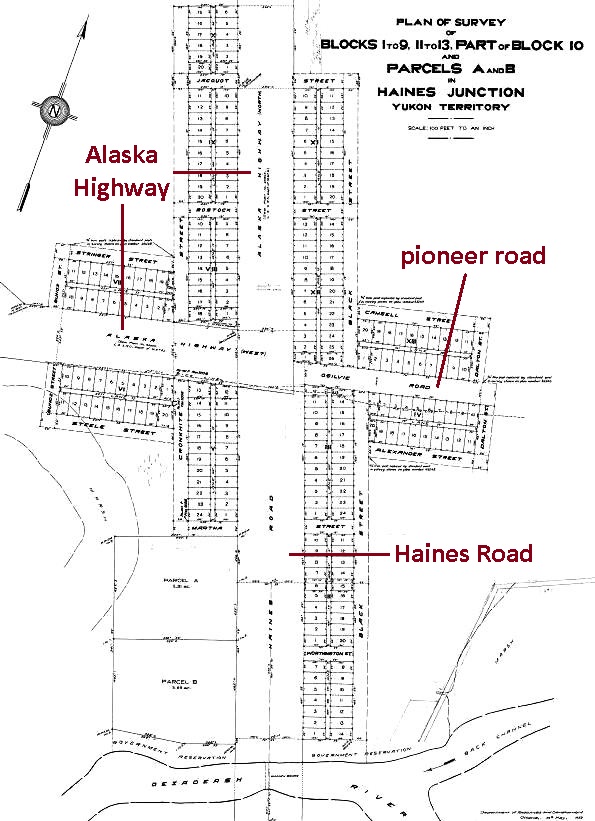

The northern wilderness wartime road project that had started out as the ‘pioneer road’ in March 1942 was officially named the Alaska Highway on July 19, 1943. It was a much different road by the end of 1943, and the two weeks needed to travel from Dawson Creek to Whitehorse a year previously was reduced to a few days. An accurate mileage measurement was made along the highway from Mile 0 at Dawson Creek, BC to its end at Mile 1422 at Delta Junction, Alaska, and by March 1944 white mileposts had been placed at every mile along the length of the highway.

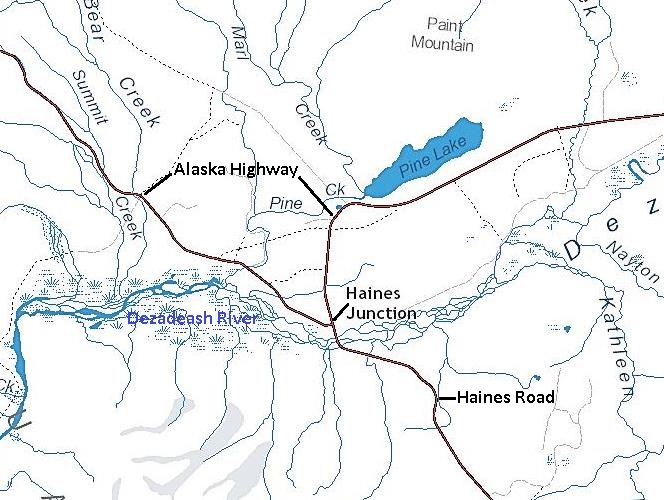

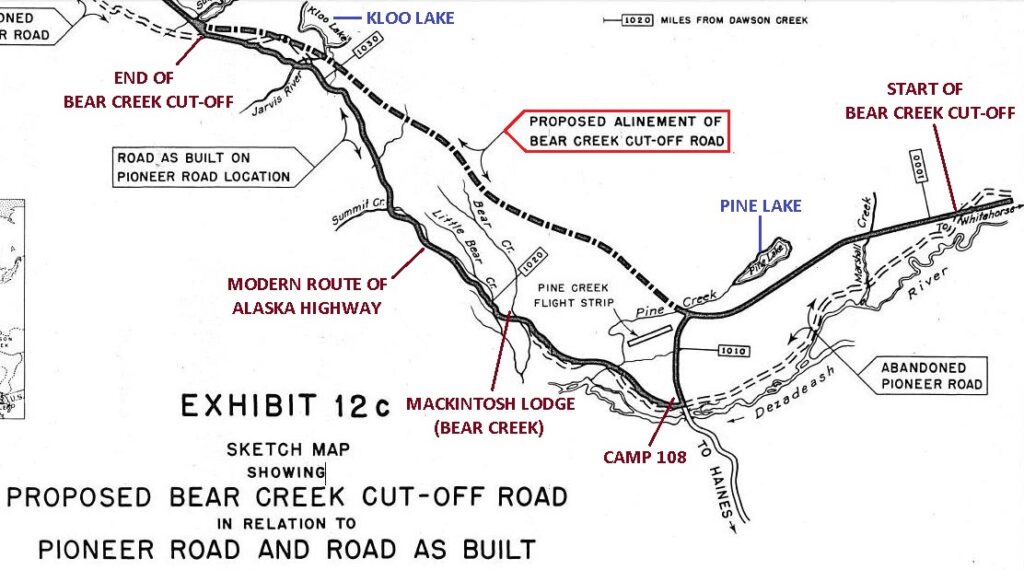

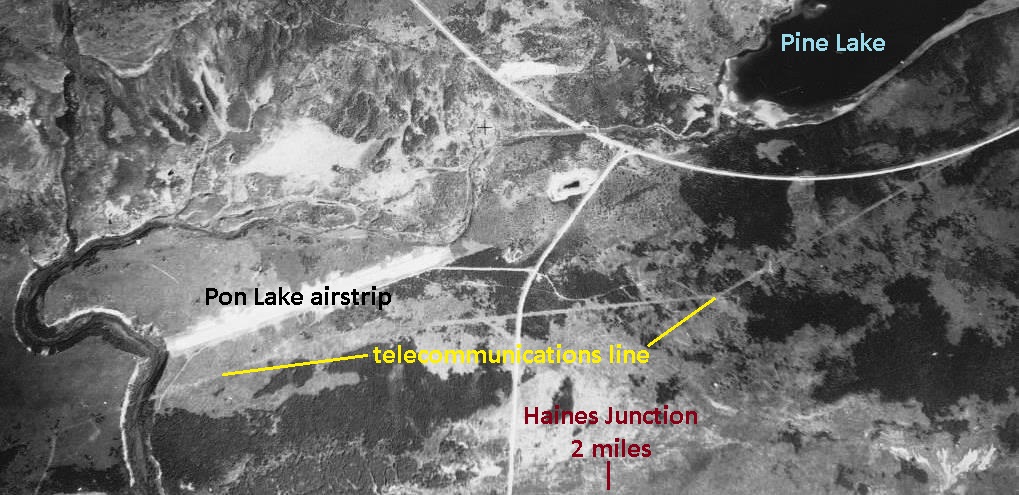

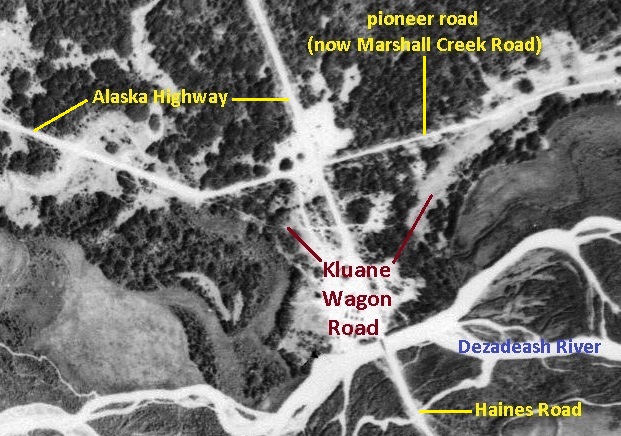

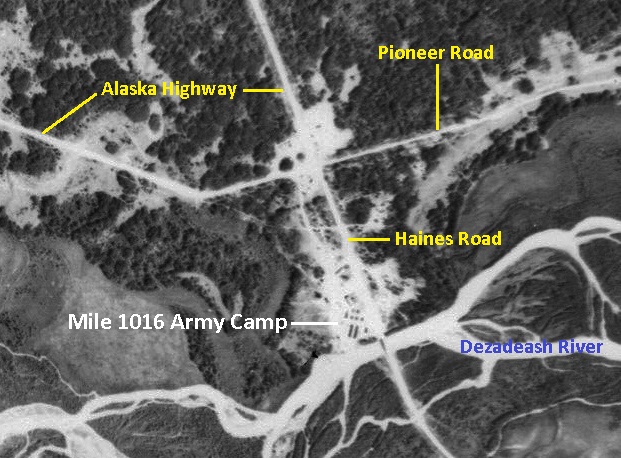

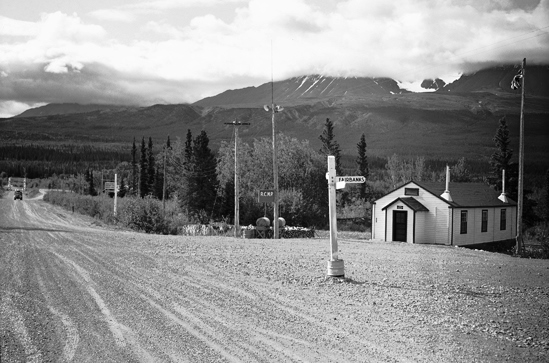

In the Haines Junction area, the abandonment of the Bear Creek Cut-off route in mid-1943 had determined that the junction of the Alaska Highway and Haines Road would be where it is today. The two highways and the remnant pioneer road (now called the Marshall Creek Road) formed a simple crossroad at the time, but the pioneer road arm is now somewhat smaller.

(Natural Resources Canada, #1994-507)

From this intersection the nearest milepost was 1016, placed a little over a quarter-mile to the north in front of where Our Lady of the Way, the iconic Catholic Church made from a US Army quonset hut, would be located a decade later. The construction camp at Mile 108 of the pioneer road was now a permanent maintenance camp at Mile 1016 of the Alaska Highway.

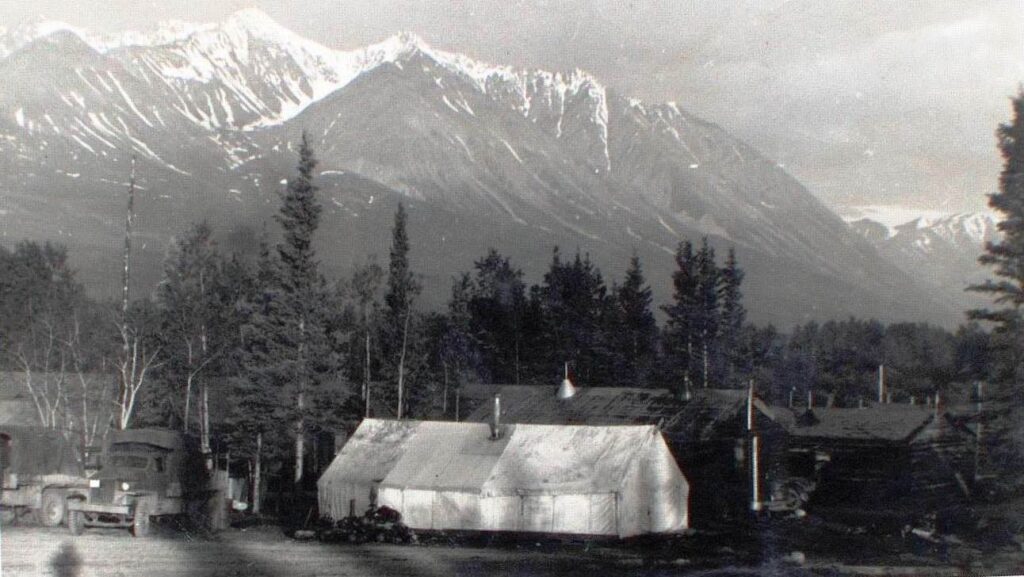

The Mile 1016 Army Camp (1943 – 1946)

By the end of 1943 the Alaska Highway and Haines Road were deemed to be completed, although they would require further construction and reconstruction to bring them to a final highway standard. The end of the initial construction meant a transition to highway maintenance, which remained an American responsibility. The agreement with Canada stated that the US would maintain the highway for the duration of the war and six months afterwards (this transfer date turned out to be April 1, 1946).

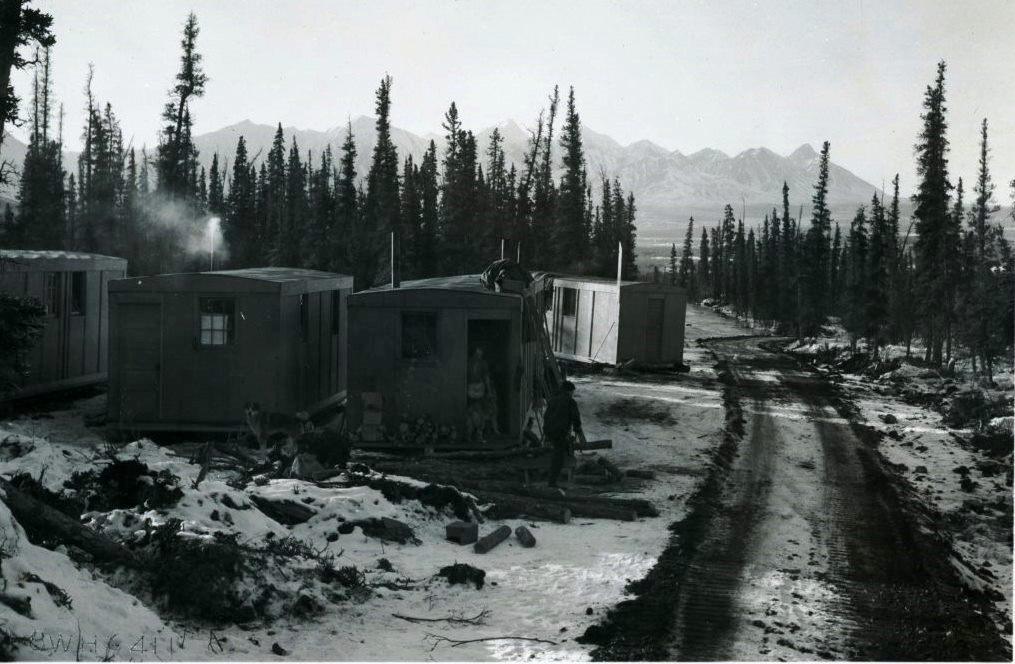

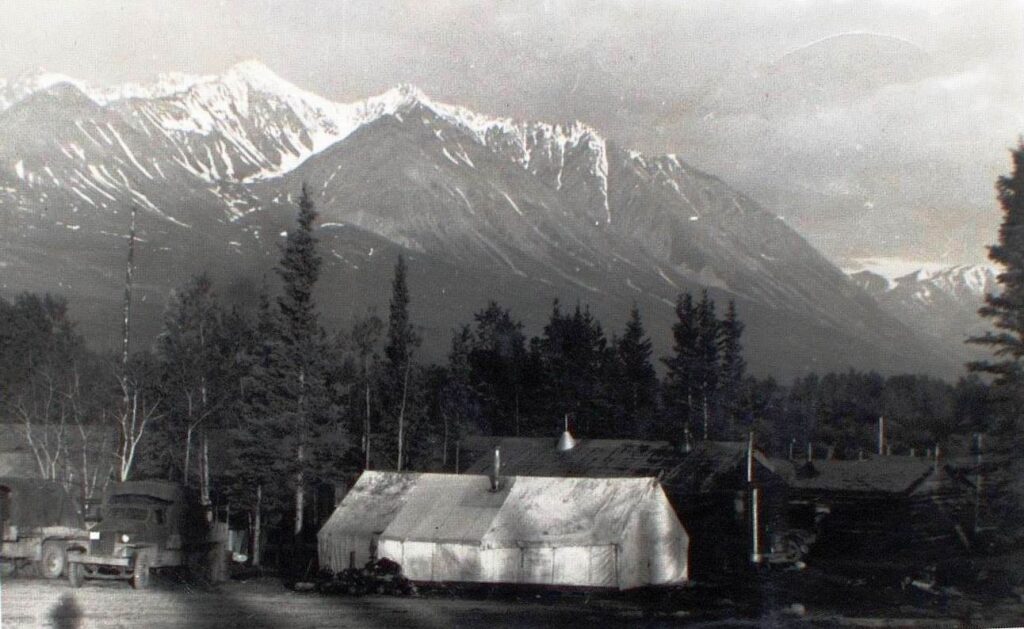

Most of the camps that had been built for the construction of the Alaska Highway transitioned to maintenance camps, with a reduction in personnel and some of the construction equipment moved out. American firms were first contracted to do the maintenance work under the supervision of the US Army and using Army equipment. This function was later assumed by the Canadian Army, so this history resulted in many of the camps being referred to as ‘Army camps’. At the future site of Haines Junction, the Alaska Highway Maintenance Camp at Milepost 1016 was locally referred to as the ‘Army camp’ for many years.

(Yukon Archives, Harry Howells fonds, Acc. 2014/40, #6 – image has been cropped)

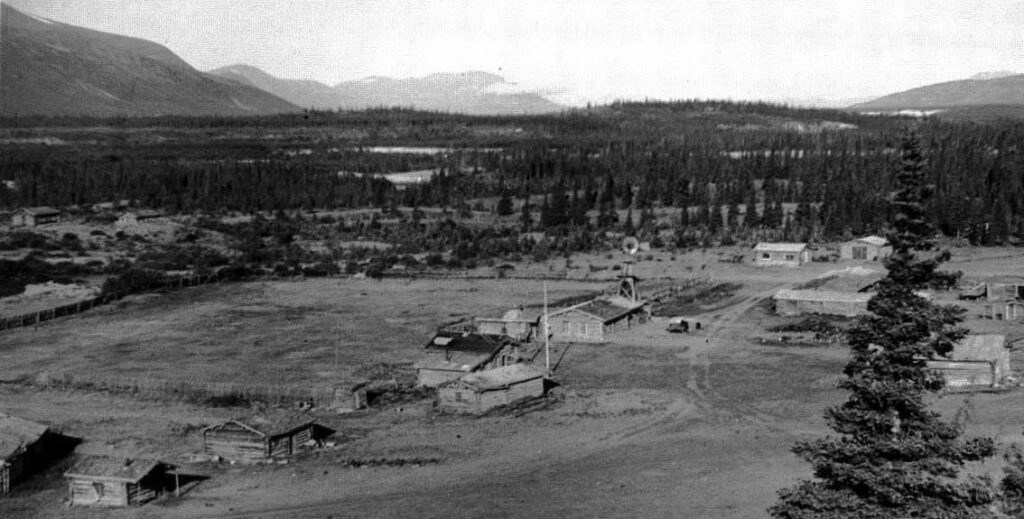

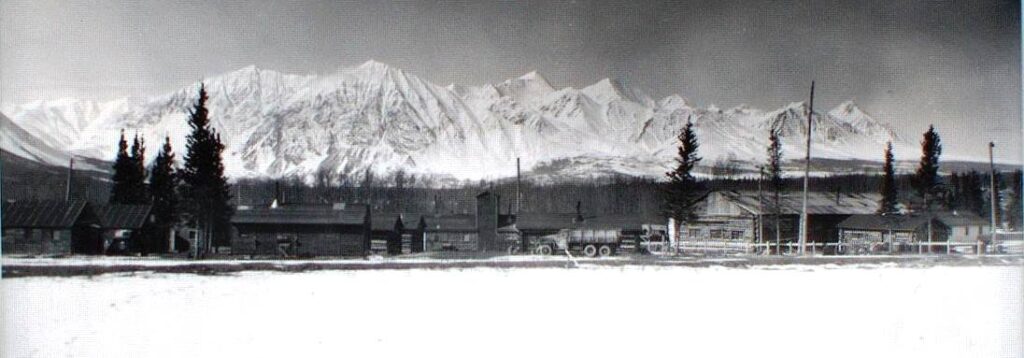

The wooden buildings shown in Glen Chapman’s 1943 photo below of Camp 108 appear to be the same buildings that are in a 1945 photo, also shown below, and they remained in use for many years after that. The 1945 photo is labelled as ‘Mile 108’, indicating that this name still had some carry-over into the time that it was becoming more commonly known as Mile 1016.

(Yukon Archives, Glen F. Chapman fonds, Acc. 2013/121, #153 – image has been cropped)

(Yukon Archives, Berta Fraser fonds, Acc. 93/114R, #4 – image has been cropped)

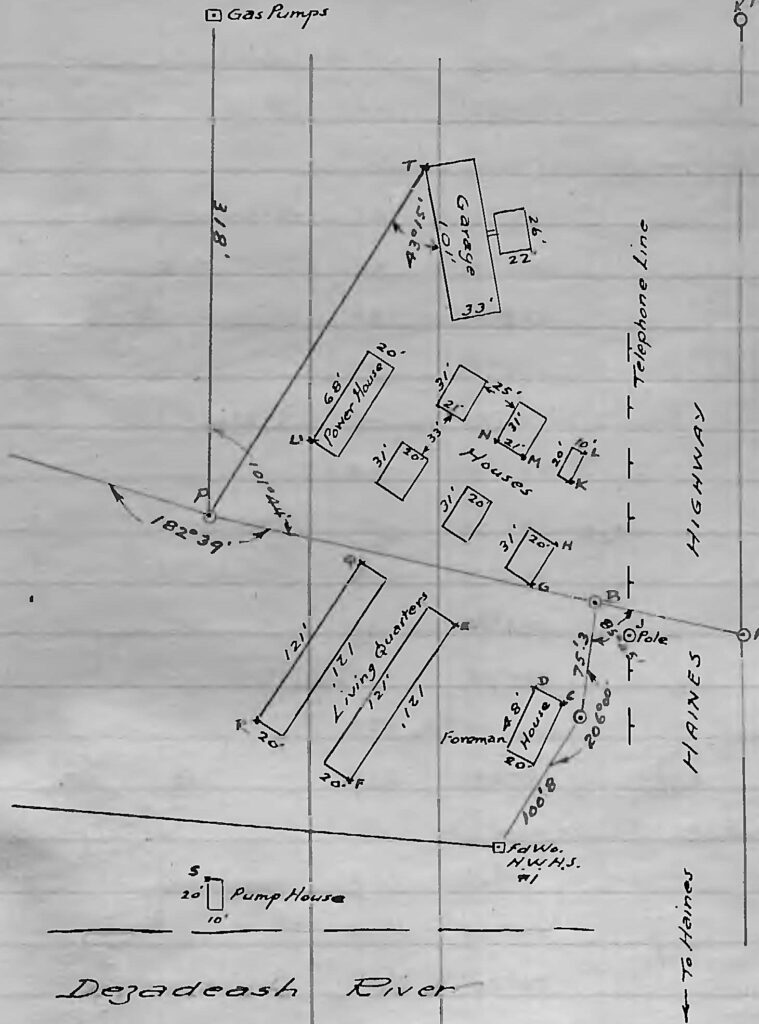

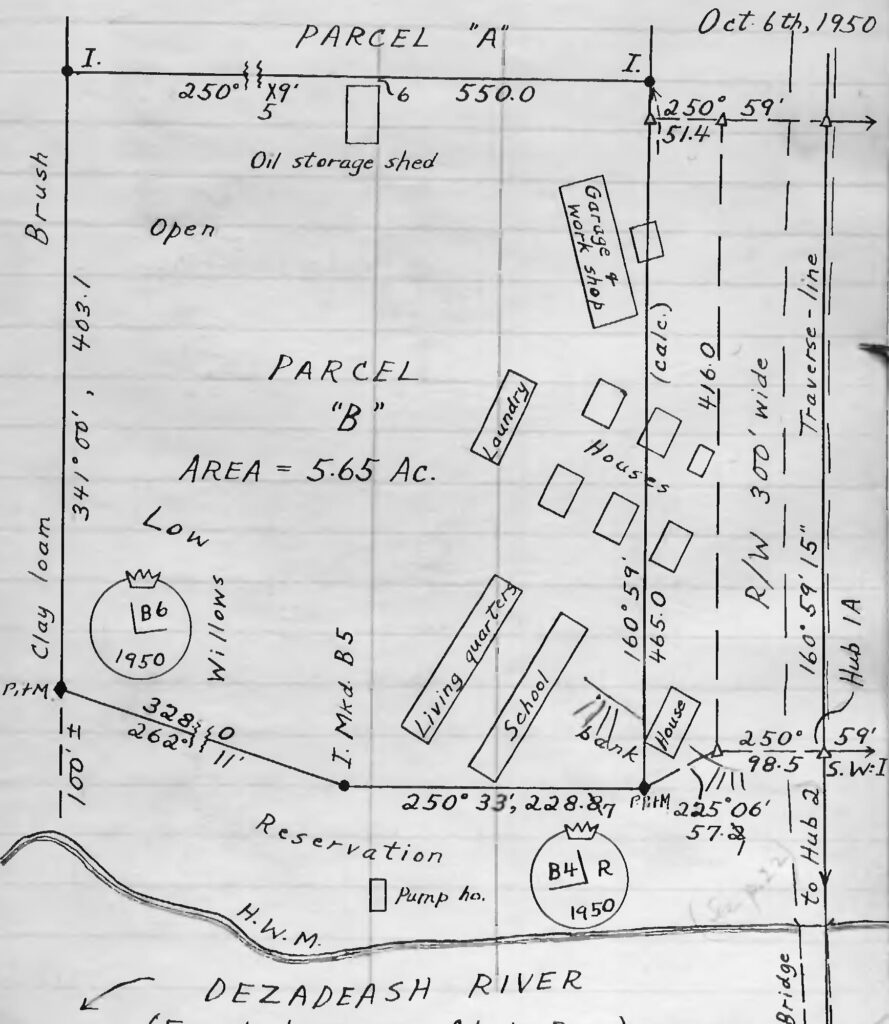

The typical construction camp buildings consisted of unpartitioned dormitory-style barracks, a combination kitchen and eating hall, an office building, a field shop (garage), a storage warehouse, a bathhouse, and a meat storage facility. The buildings in the 1945 photo above remained as the permanent camp and can be matched up with those shown below in a preliminary survey field book from July 1949. The two buildings cut off at the left edge of the photo are the long (121 feet) living quarters shown on the sketch.

(Canada Lands Survey Records, FB23258, p. 15)

Twenty feet seems to have been a standard width for many buildings, perhaps sized to what the roof trusses could handle without requiring internal support. A report in September 1944 showed that the Mile 1016 camp buildings had wiring and plumbing, stove oil space heaters, and water piped in from the river, but there was no phone service at the camp.

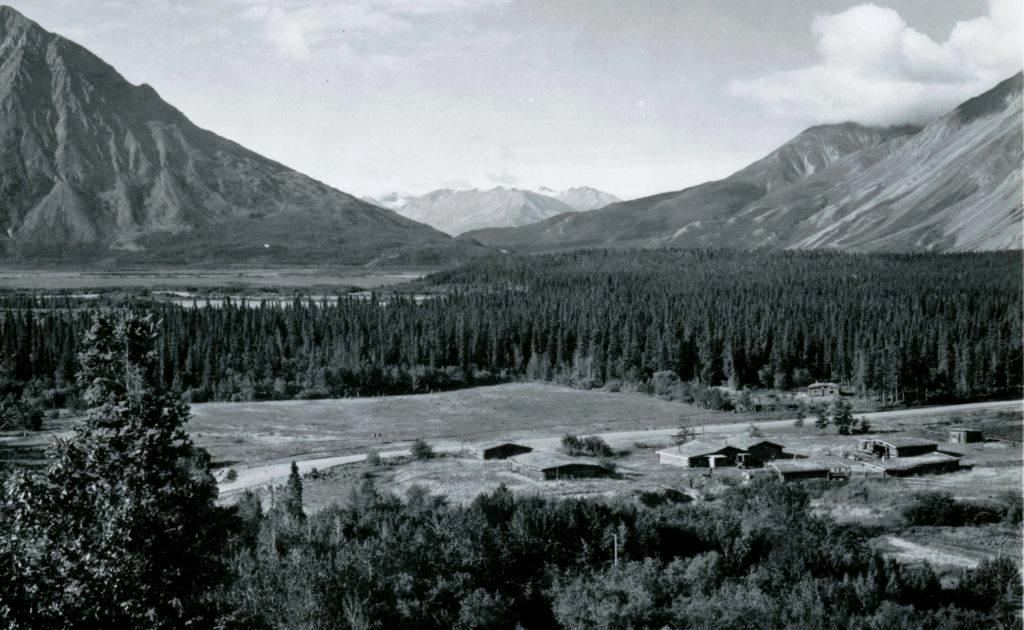

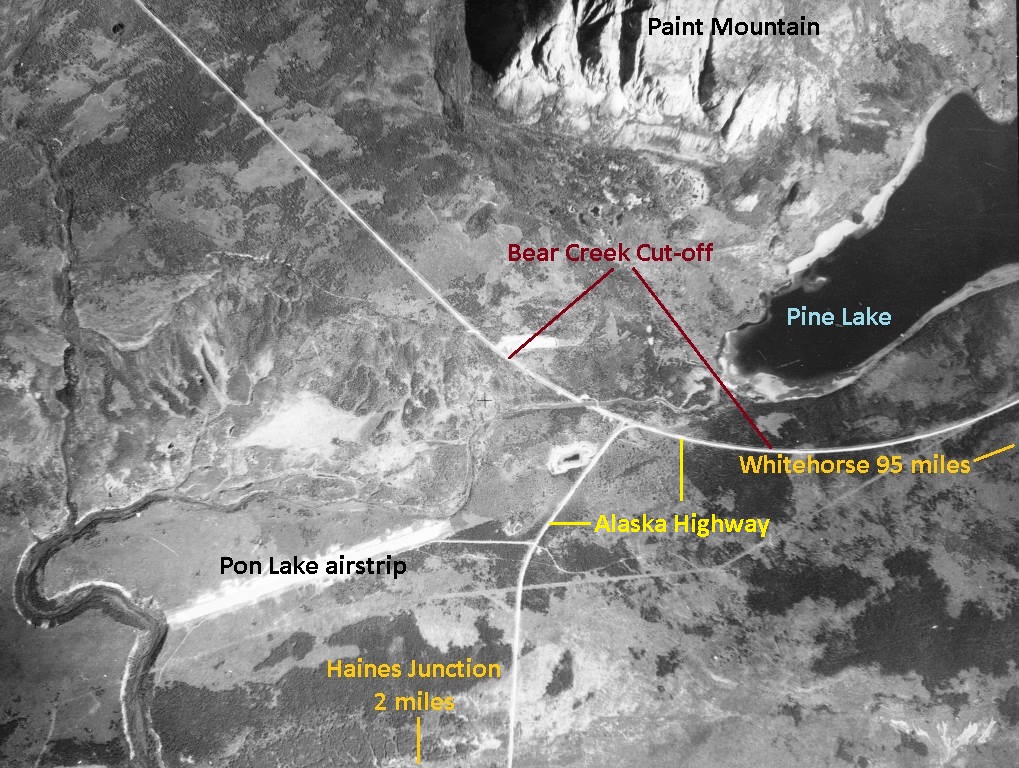

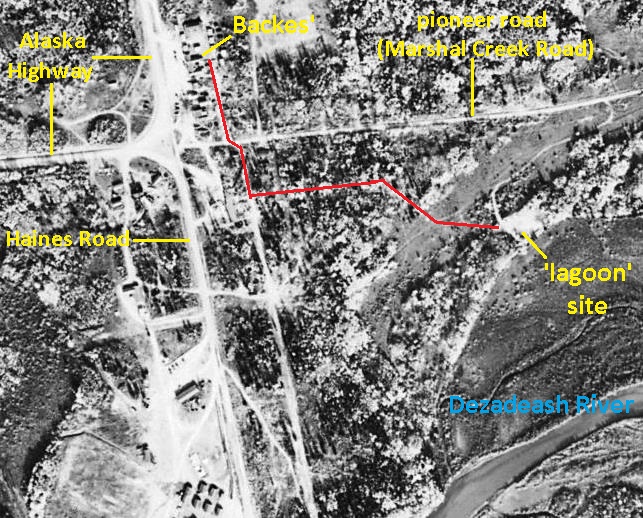

The configuration of buildings in the above sketch can be seen in an air photo from the previous year of 1948. This air photo below shows the location of the Mile 1016 camp (formerly Camp 108) in relation to the Alaska Highway, Haines Road, pioneer road, and the Dezadeash River.

(National Air Photo Library, A11539, #133)

A March 1944 inspection of camp buildings along the highway described them to be “of a quite temporary nature”, perhaps built in a hurry with no thought of permanency. However, in the case of Mile 1016 they ended up being used for about 15 more years. This ‘temporary nature’ may be why a teacher living in one of the barracks buildings in the mid-1950s said that “with the freezing and thawing of the ground, the partitions would shift, leaving a space at the roof or floor”. Charlie Eikland Sr., who lived in Haines Junction from 1949 to 1955 and sometimes cut firewood with his father Pete, said that many cords were hauled to the Army camp because the oil space heaters in the buildings could not keep up in the colder weather.

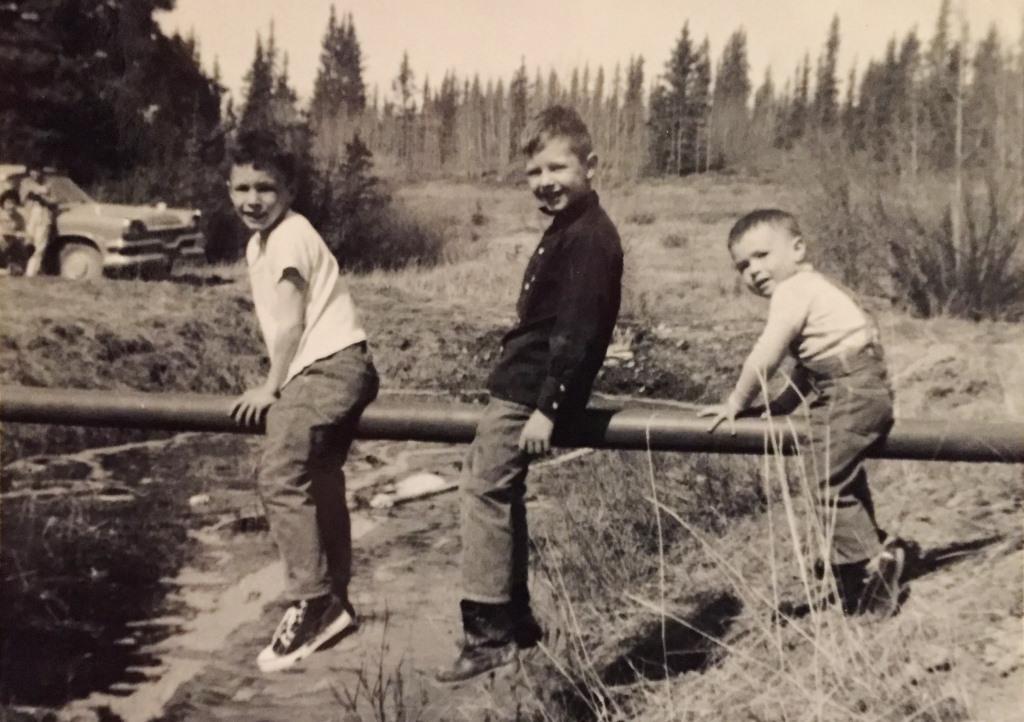

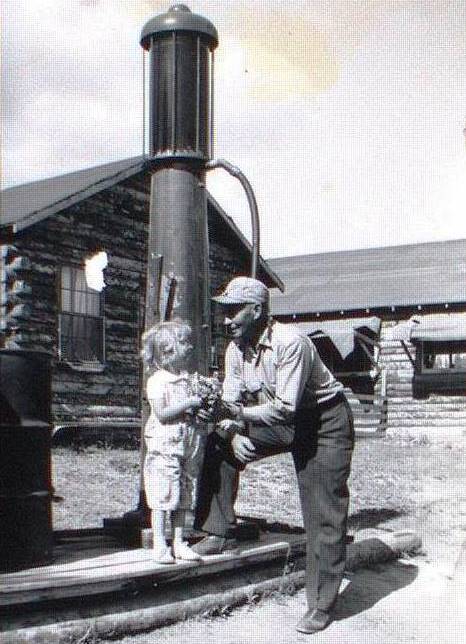

The Alaska Highway maintenance camps were on average about 40 miles apart with 11 employees. Every second camp was a ‘hotel camp’ that provided room and meal services and a fuel dispensing facility to authorized travellers (at this time the highway was not yet open to the travelling public from the ‘outside’). These camps had on average another eight employees for the accommodation and fuel service. Mile 1016 was a hotel camp, but one of the smaller ones, and in September 1944 it had a total of 16 people, comprised of 11 men, three women, and two boys aged nine and six.

(Yukon Archives, Backe Family fonds, Acc. 2004/70, #11 – image has been cropped)

By early 1944 the US Army had developed a plan for a smooth transition of the maintenance program to the Canadian government. The plan had two primary personnel elements: recruiting Canadian workers to replace the American contractor employees to avoid a wholesale turnover in personnel; and establishing a stable and permanent workforce by encouraging and assisting married men with families to live at the camps.

It was believed that remodeling the existing camp buildings and furnishing them to accommodate families would more than offset the expense incurred in personnel turnover. At Mile 1016, the barracks were partitioned off for living quarters and furnished, while other spaces served different purposes, including a school in 1949 that served the community for most of a decade.

At Mile 1016 on August 31, 1945, there were four families with a total of six children, four of whom were school-aged. A school service was not provided there, but it was at larger camps such as Destruction Bay, which had 16 school-aged children.

The war officially ended on September 2, 1945, and on April 1, 1946 the control and maintenance of the Canadian portions of the Alaska Highway and Haines Road was transferred to the Canadian Army. For the most part the maintenance camps were by then staffed with Canadian personnel and the transition was relatively seamless.

The Mile 1016 Army camp carried on its highway maintenance function for many more years. The first foreman after the transfer of the highway to the Canadian Army was Al Bock and there were six equipment operators working under him. From 1947 to 1952 the foreman was Ray Russell, who had his wife and three children living at the camp with him.

(Bertram Arthur Deer collection)

The first Haines Junction school opened in 1949 in one of the barracks buildings, as shown below in a 1950 survey plan. At first it was a one-room school, with Alene Darnall as the first teacher. She boarded in a hotel room at John and Sally Backe’s Haines Junction Inn until a section of the school building was renovated for teachers’ accommodations. This created a two-room school, with grades 1-4 in one end and grades 5-8 in the other and the teacher accommodations in the middle.

(Canada Lands Survey Records, FB23257, p. 21)

(Bertram Arthur Deer collection)

Over the years the Army camp in its original location served more than just a highway maintenance role . In addition to the first school space, it provided the first recreational facilities as the town started to develop, including a skating rink, curling rink, and a canteen and room for showing movies. The camp was part of the community center for many years until it was relocated across the highway in 1960.

Haines Junction Begins – Government Developments and Area Activities (1945-1950s)

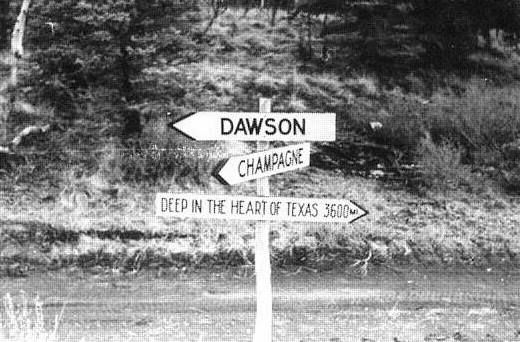

There is no definitive moment in time when the name Mile 1016 changed to Haines Junction. Previously, ‘Haines Road Junction’ and ‘Haines Cut-off Junction’ were commonly used, but ‘Haines Junction’ seemed to start standing on its own in the late summer of 1945. However, it was used interchangeably with ‘Mile 1016’ for many years after that.

(Yukon Archives, MacBride Museum collection, Acc. 82-59, #16 – image has been cropped)

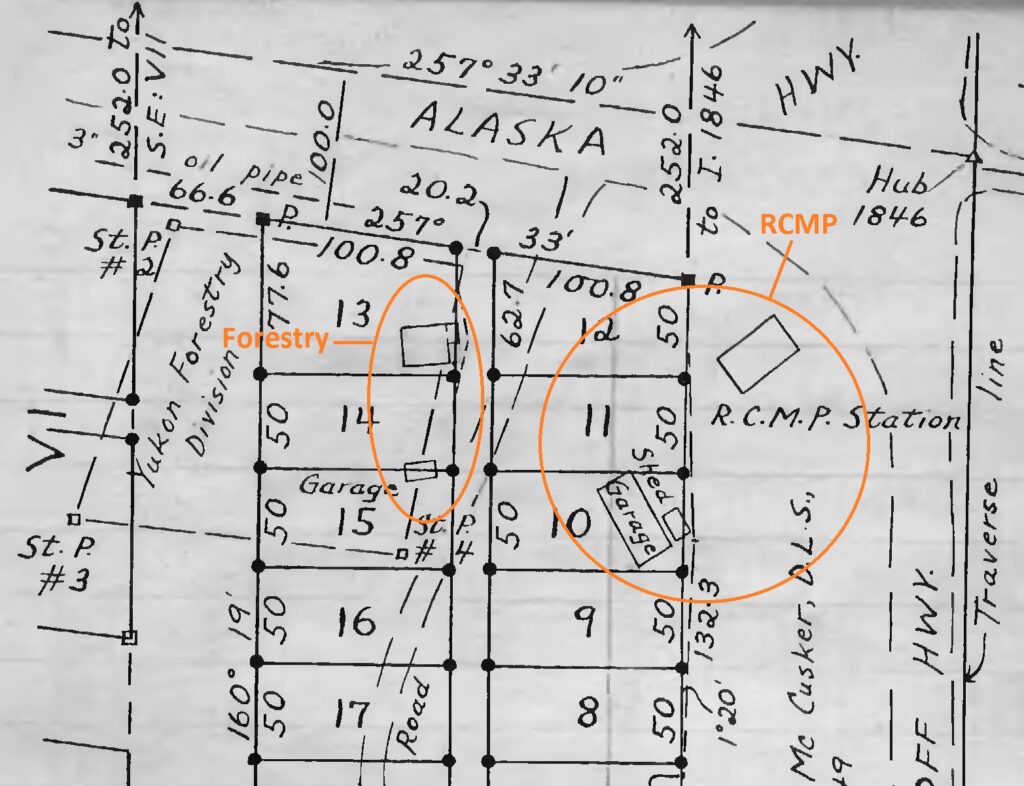

Following the establishment of the Army camp in 1943, the next known developments in the Haines Junction townsite were governmental ones. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) set up a station in 1945 on the southwest corner of the highway junction. By 1950 they had a 20’x40’ building on the site, with the back part of it possibly serving as quarters for the member(s), and a 22’x49’ garage.

Betty Karman, an early and long-time resident of Haines Junction, said that the RCMP first had a metal building called a quonset hut as an office. This would have been a US Army building that was moved to the site, and according to Betty it is now located behind the Source Motors garage on the Alaska Highway a mile west of Haines Junction.

A parcel of land on the Alaska Highway that was applied for in 1946 was described as being “directly across the highway from the present RCMP Checking Station”. This is indicative of the role of the police in monitoring traffic on the Alaska Highway during the periods it was closed to public travel and permits were required. There is also information indicating that the RCMP here issued permits for travel on the Haines Road in the later 1940s.

(Yukon Archives, Rolf & Margaret Hougen fonds, Acc. 82/346, #20 – image has been cropped)

The first police officers were Corporal Russel (‘Rusty’) Martin and Constables Raymond Johnson and Joseph Romain. They all started in 1945, with the first two staying until January 1949 and the third is uncertain. Cpl. Martin was to have a somewhat deeper connection to the community, including a second posting.

In July 1949 Constable Bertram Arthur (“Art”) Deer was posted to Haines Junction and took a number of rare photos of the community in its infancy and of the area while on his patrols on the Alaska Highway. These photos are contributions to the area’s historical record and some have been provided by his son Peter for this article. Cst. Deer served in Haines Junction until being transferred to Watson Lake in 1951, and went on to become an accomplished photographer and instructor in photography.

(Bertram Arthur Deer collection)

Sometime in the latter 1940s, before the summer of 1949, the Yukon Forest Service also established a presence at Haines Junction in the same area as the RCMP. At first there was a 20’x24’ patrol cabin and a small garage, but a larger house was built a few years later, with Joe Langevin becoming the first Forestry official to be stationed there.

(Canada Lands Survey Records, FB23257, p. 19)

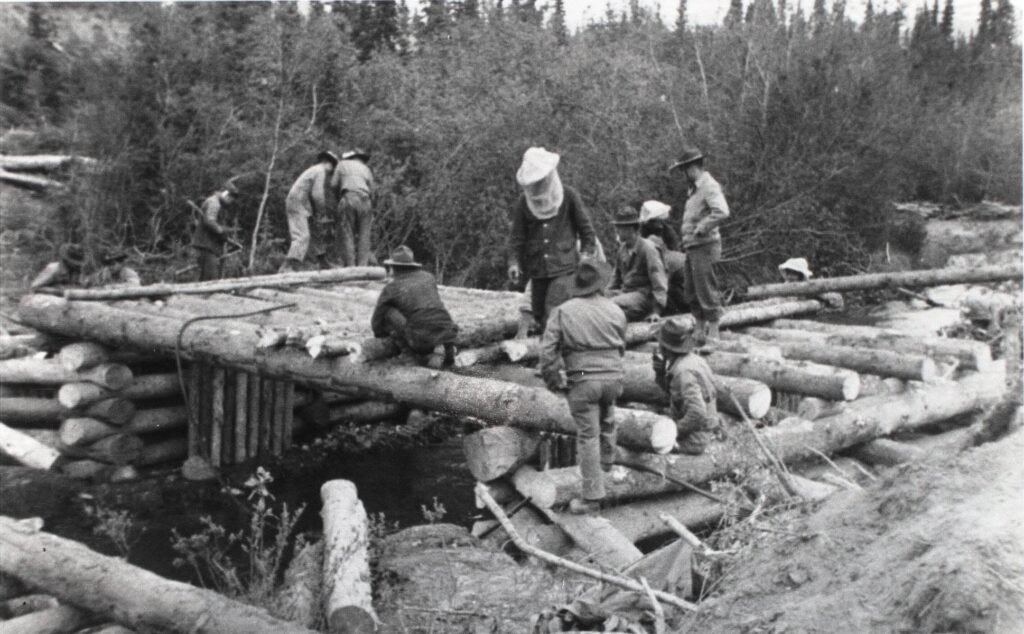

A Government of Canada project that was exempted from the 1942 one-mile non-development reserve on either side of the Alaska Highway was the 800-acre Dominion Experimental Farm at mile 1019, three miles northwest of Haines Junction. It had been identified in 1943 as a site for expanding the northern agricultural knowledge base, with the thought that the Yukon might be able to feed itself.

(Hugh Bradley collection)

In the summer of 1944 employees arrived to construct buildings and clear land, and a number of local people were also hired to work on the farm, some of them living and working there for many years. The Experimental Farm became an important part of the Haines Junction community until its closure in 1970.

(Hugh Bradley collection)

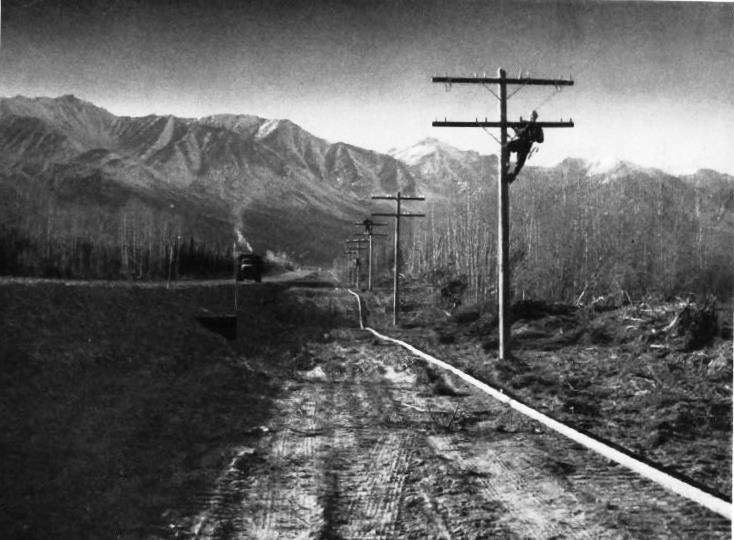

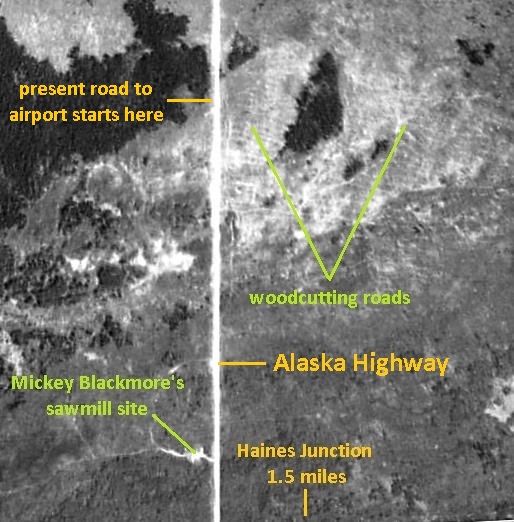

There were other activities around Haines Junction, one of them a couple of miles to the north that is familiar to this area almost 80 years later. A March 1944 highway inspection trip reported passing 21 trucks between Whitehorse and Kluane Lake, and 11 of them were hauling firewood to Whitehorse from “near the Haines Junction”. This was fire-killed wood from a forest fire that went through the Haines Junction area in 1938, according to late long-time resident Ed Karman. Charlie Eikland Sr. said that he sometimes worked with his father cutting wood near the airport for a man named Percy Thompson, who hauled a lot of wood to Whitehorse in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The area it was harvested from is shown in a 1964 air photo below, where there is a multitude of what were undoubtedly woodcutting roads.

(National Air Photo Library, A18400, #246)

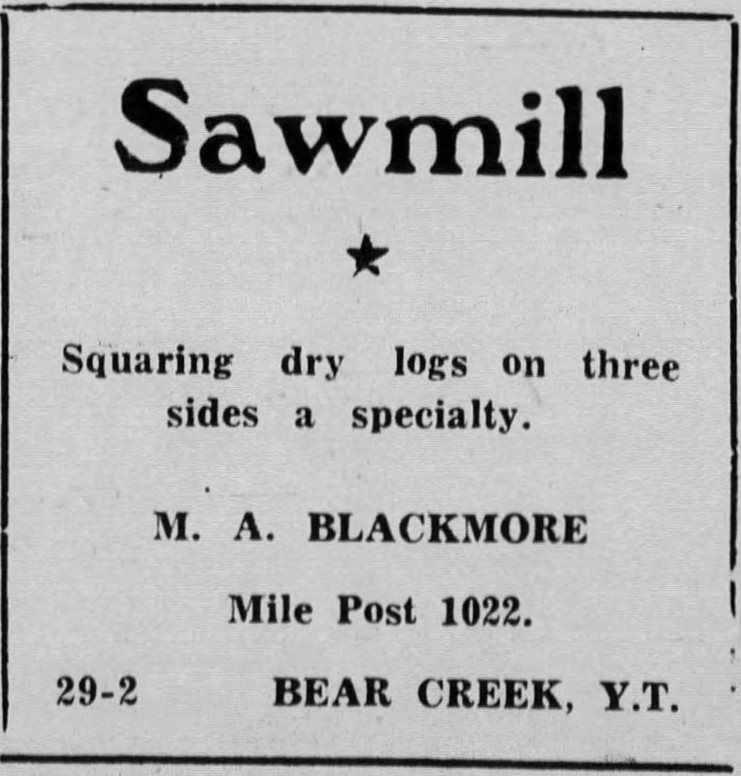

A short distance south from the woodcutting area, across the highway from the present Haines Junction landfill, is an old sawmill site where lumber was cut from the burned wood. It was owned and operated by Mickey Blackmore, who advertised in 1946 that he was milling three-sided dry logs at Bear Creek (Mile 1022). Either before or after this he had the mill set up at the site north of Mile 1016 (see location on air photo above). Charlie Eikland Sr. said that his family lived in a shack at the sawmill site in 1949, but the mill was gone by then.

(Whitehorse Star, 19 July 1946)

In July 1946 a 160-acre homestead 2½ miles east of Haines Junction along the pioneer road was staked by Harvey Brooks under the Veterans Land Act. He established a small farm there and later developed another piece of land as a potato field about a mile west of Haines Junction along the Alaska Highway. He sold hay and vegetables from these properties to Haines Junction residents and others for many years.

(Bertram Arthur Deer collection)

Land Staking and the 1949 & 1950 Land Surveys (1946 – 1950)

Interest in acquiring land at Haines Junction began in the summer of 1946 when the restrictions on development along the Alaska Highway were about to be lifted. Six land parcels for business and residential purposes were staked out on the ground in the area of the highway junction that year, followed over the next three years by the staking of an additional 14 parcels for a variety of sizes, ranging from one acre to 160-acre homesteads. Of these 20 total parcels staked, only eight amounted to anything and four of them were to cover existing developments, including the Army camp.

After taking over control and maintenance of the Alaska Highway on April 1, 1946, the Canadian government lifted the prohibition on land development along the highway two months later so that private enterprise would invest in establishment of facilities. However, the highway was still closed to unauthorized public travel, so it was a Catch-22 situation. Part of the reasoning for restricting travel was the scarce accommodation and repair services in place to look after the safety and well-being of travellers, but entrepreneurs were reluctant to establish these services with few potential customers.

At Haines Junction, there had been an additional uncertainty that would further hinder land acquisition and development. This was to do with the future of the Haines Road because of ambivalence by both the American and Canadian governments about maintaining it. In August 1944, the US Army announced that it was abandoning its interest in the road, and as late as January 1947 the Canadian government was waffling about keeping the road open at all.

These positions were not sustained and the road continued to open every summer, at first only for relatively short periods, and it was not until 1963 that it became a year-round highway. However, the uncertainty during those first few years kept the Yukon land management process from effectively dealing with the demand for land. In the meantime a few land applicants forged ahead with their developments, despite having no tenure to the land nor certainty about how much business might come their way.

In January 1947 a government land official stated that “development at this site is entirely dependent upon whether or not the Haines Road will be maintained and operated. There would appear to be every likelihood that the Canadian government will not maintain [it] … even during the summer months”. He went on to say that without the Haines Road, Mile 1016 would be just another spot along the Alaska Highway.

Continued internal discussion led to the determination that as an interim measure, applicants could be granted land of appropriate sizes for their needs on a ‘permission to occupy’ basis, but not to purchase. The government’s hesitancy to release land due to the uncertainty about the Haines Road continued into 1948, when in January it stated that “the Department … is not at present favorably inclined towards a subdivision of land adjacent to Mile 1016, Haines Road junction”.

It was not until the end of 1948 that the Canadian government finally came to the conclusion that “in view of the interest displayed in the acquisition of lands … it will be advisable to have the lots properly laid out by a surveyor as a subdivision”. It was stated that this survey would be included in the 1949 Yukon survey program, which would have come as the second piece of good news that year to the business hopefuls. On February 25, 1948 the Canadian Army had been ordered “to tear down the huge gate … at Blueberry [in BC at Mile 100 of the Alaska Highway] so traffic may flow freely”.

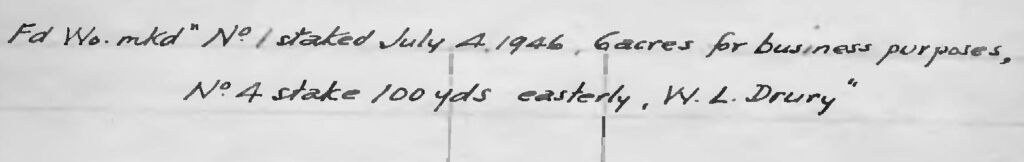

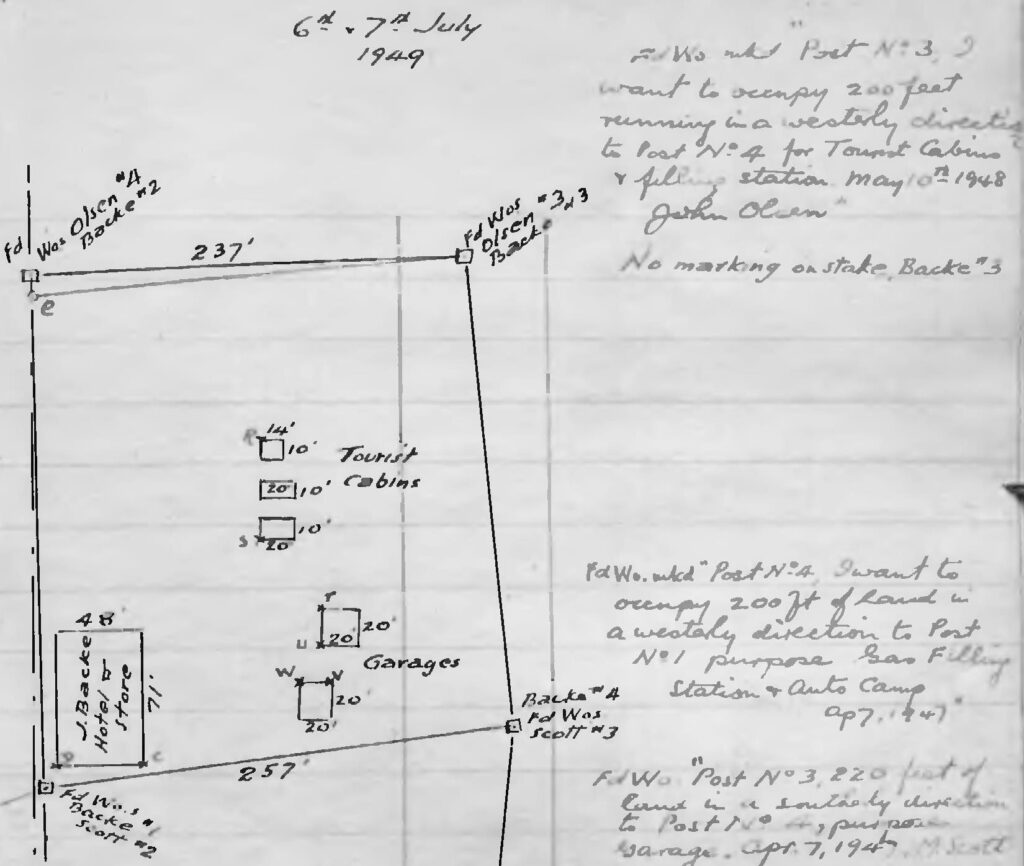

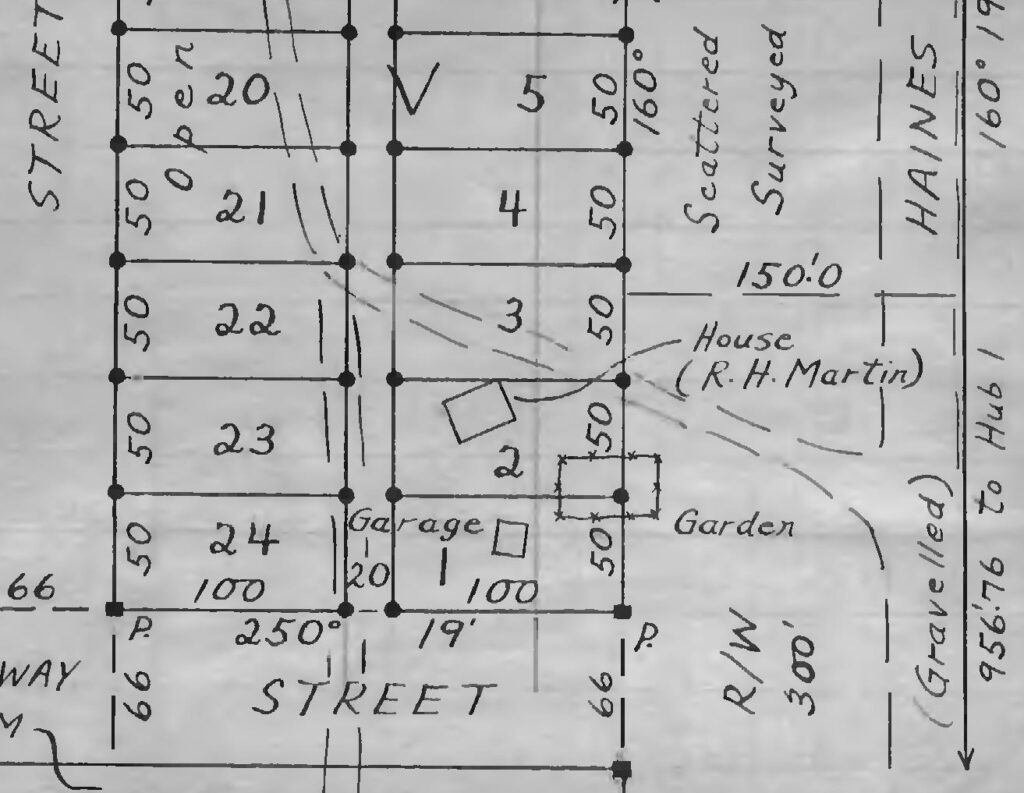

The 1949 survey was intended to produce a subdivision of legally surveyed lots, but only a preliminary survey was undertaken. A surveyor from Ottawa spent 10 days with a crew in July 1949 measuring and mapping the relative locations of all the land applicants’ stakes and recording the data written on them. This data included the name, date of staking, distance and direction to the next stakes, and proposed purpose for the property.

(Canada Lands Survey Records, FB23257, p. 1)

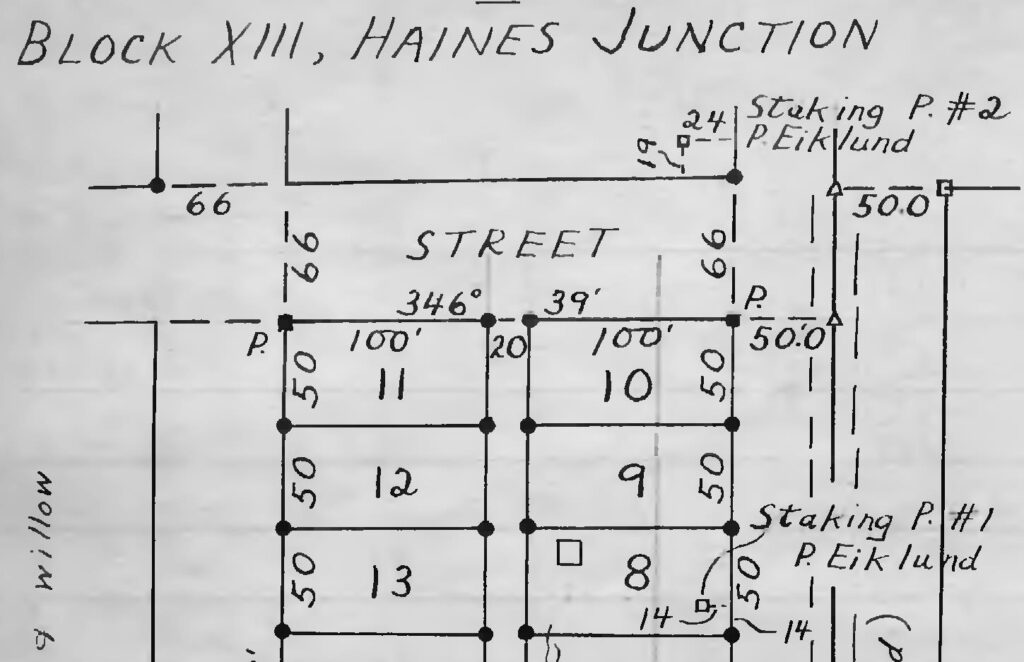

The surveyor and his crew returned in September and October of the following year to lay out a townsite of 13 blocks containing 258 lots, the vast majority of them 50’x100’ in size. He also surveyed out two large lots totalling 11.5 acres that covered the Army camp area beside the Dezadeash River.

(Canada Lands Survey Records #41519)

Both the 1949 preliminary survey and the 1950 final survey produced fieldbooks that are very valuable for documenting the early history of developments at Haines Junction. They contain information about the locations, sizes and ownership of the buildings that were in place by the fall of 1950.

The small (50’x100’) Haines Junction lots, though surveyed in the fall of 1950, did not become available for sale to individuals or businesses until 1952, six years after the staking of land began. By that time, the government had a list of 18 land applications, some of them from people who had already put up buildings, and some by people who had since left the area. The government’s direction was that “all the above applications should be resubmitted to conform to the approved and confirmed plan of survey”.

When the lot sale finally happened, the applicants who had come in the latter 1940s to stake land and erect buildings were rewarded for their risk and faith that the community held a future for them and their families. Three of the entrepreneurs proved this correct and were successful, but one was not, and another who started out at the junction relocated after a year to Canyon Creek to build a business there.

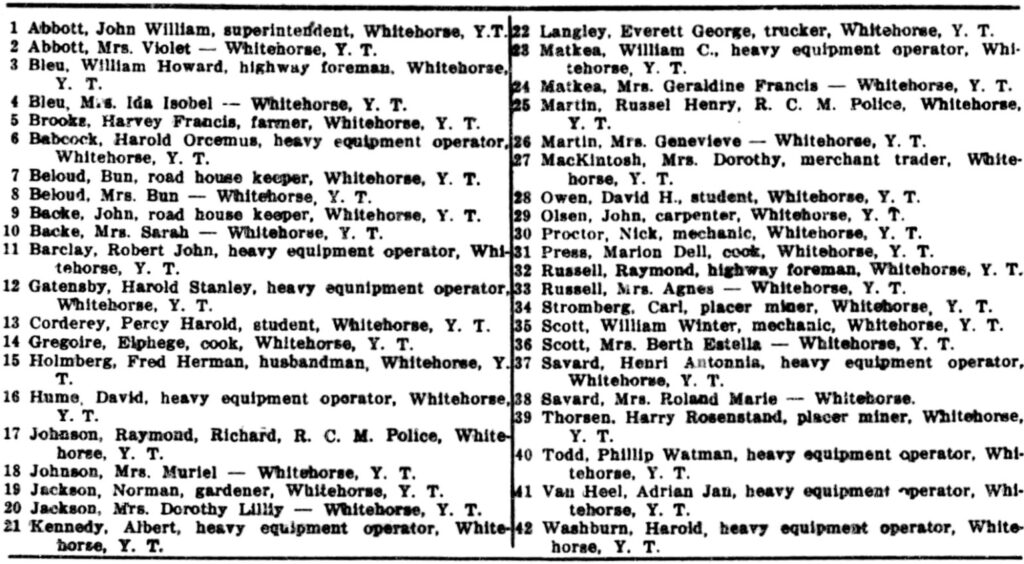

A Haines Junction voters list for the 1949 federal election provides information about the early residents of the community, at least those eligible to vote. There are 42 names on the list, but the 11 married couples and another known married man whose wife is not included would have added a number of children to the population figure.

The list shows 12 names that are associated with the highway maintenance operation and up to seven more that may also be. There are three businessmen, three Experimental Farm employees, two placer miners, two RCMP members, and others such as students and a farmer. There is no employment shown for the women, but three were known to be involved in businesses, two of them alongside their husbands and one a widow.

(Ancestry.ca, Canada, Voters Lists, 1935-1980 for Yukon-Mackenzie River, Alberta)

Building a Community – the First Private Developments (1946-1950)

The following sections profile the first businesses along with the first private residences at Haines Junction. After the town lots were released for sale, the community started to grow with gradually more residential, commercial and institutional developments.

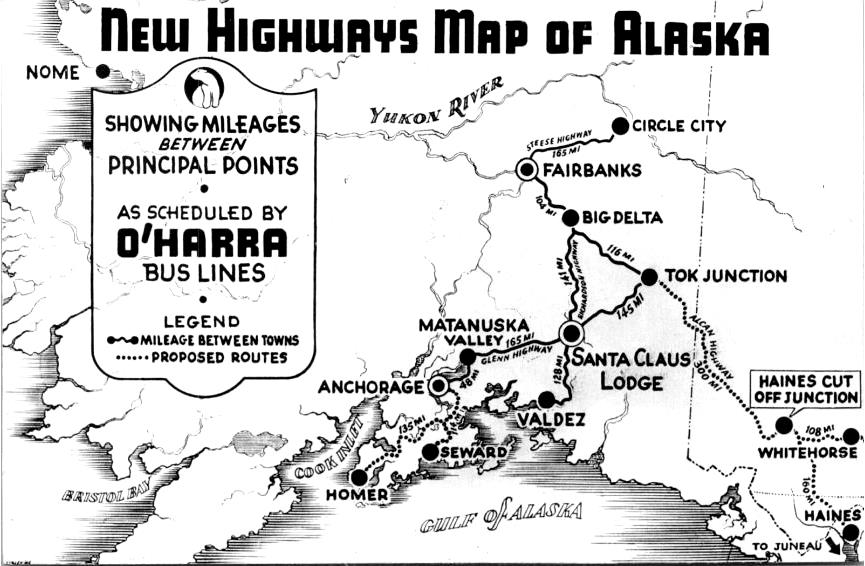

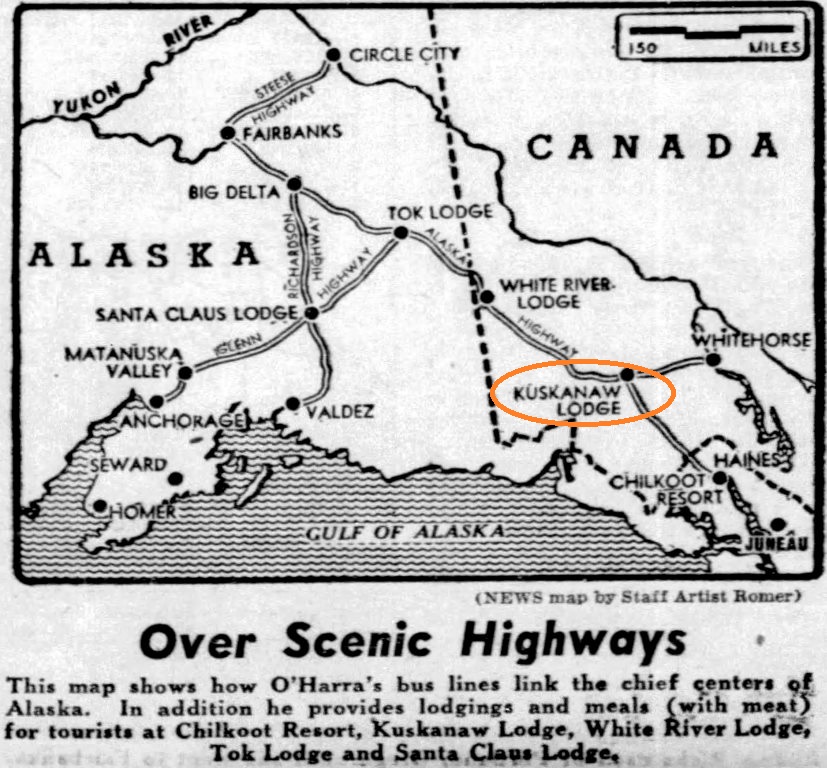

O’Harra Bus Lines

The first known private entity to use, stake and apply for land at the junction of the highways was the Alaska-based O’Harra Bus Lines, owned by Kenneth O’Harra. On May 6, 1946 the company wrote to the Canadian government that for the bus service it had been running between Whitehorse and Fairbanks since August 1945, it wanted to establish “proper overnight stopping places” along the highway. One of these locations was at the junction of the Alaska Highway and Haines Road, where three to five acres of land on the northwest corner of the highway intersection across from the RCMP station were requested to establish facilities for accommodation, food, and bus maintenance.

(Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, 2 April 1973)

On June 20, 1946, land was staked by O’Harra employee Harvey Perrin for a “bus depot and maintenance camp” at this location, but he staked a much larger parcel of 12.4 acres. Perrin and his wife Lillian were living in tents on this land and were serving lunch to the O’Harra bus passengers.

On the Labor Day weekend, O’Harra initiated a weekly Haines Road service with an inaugural trip to Haines, and on September 12 extended it to Juneau by connecting with a boat service from Haines. O’Harra made its last trip in mid-October before the Haines Road was closed for the season, and it turned out to be the company’s final trip on that road.

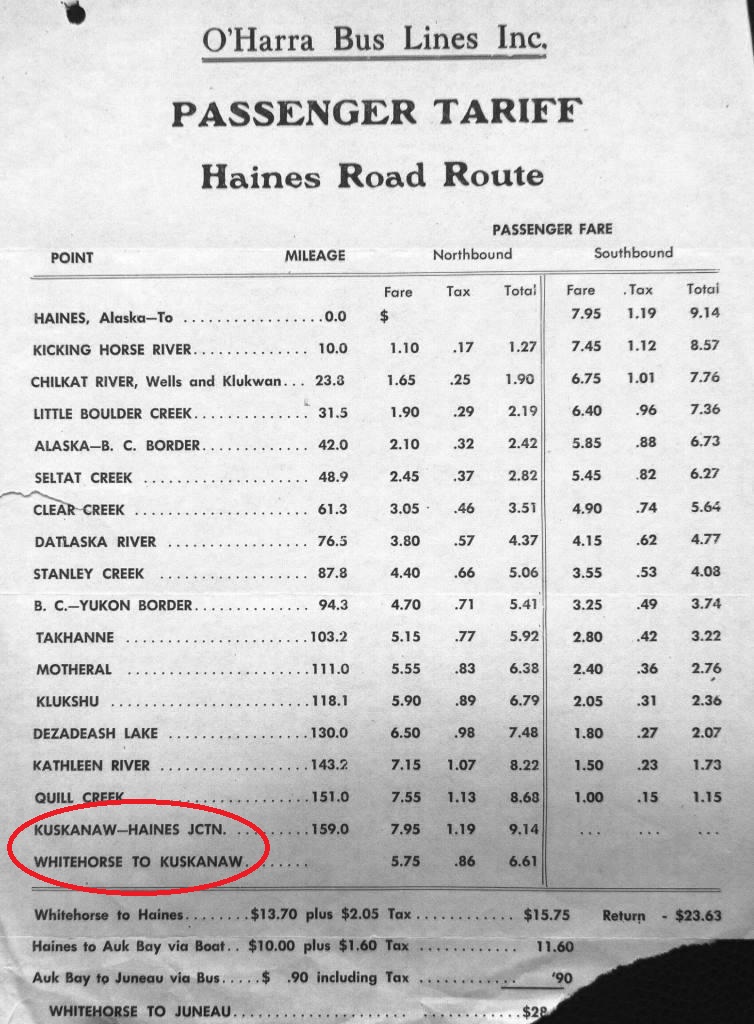

The name ‘Kuskanaw’ began to appear in connection with O’Harra Bus Lines’ business at Haines Junction. A tariff sheet produced by the company for its Haines Road operation showed ‘Kuskanaw’as its name for Haines Junction. It also appeared on a map in a New York newspaper article showing the bus lines’ routes in Alaska and the Yukon. The Kuskanaw name appears to derive from a word in the Koyukon language of western Alaska that means ‘community dance hall’.

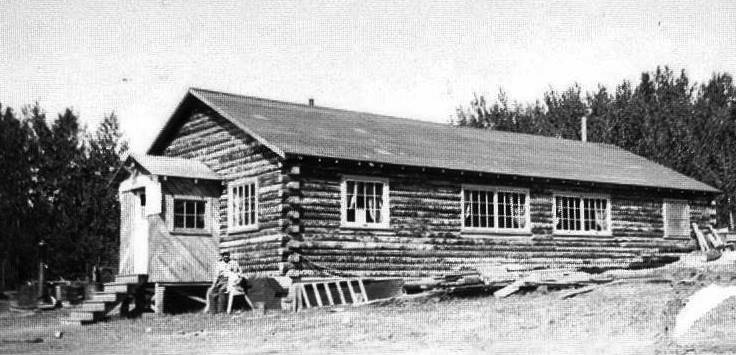

(Yukon Archives, GOV 1674, file 35959)

After submitting its application for land, O’Harra was advised that it could not erect permanent buildings at the site, but by late October it had some in place that the government accepted as “temporary occupancy” because they were on skids. They were 28’x52’ and 24’x28’ in size, built of logs that Kenneth O’Harra said he helped to cut himself, and were evidently put together into a U-shape at some point. They appear to have been milled on three sides, so it is probable they were produced by Mickey Blackmore’s sawmill north of town.

The building was called Kuskanaw Lodge, and in a government report of early January 1947 it was referred to as a “small hotel”. By March it was reported that meals were obtainable there, but no accommodations were being offered until a regular bus service on the Haines Road was established. At some point an 11,000-gallon fuel tank was installed on the property, presumably underground as it does not appear in photos of the site.

(Yukon Archives, Backe Family fonds, Acc. 2004/70, #2 – image has been cropped)

Along with the name Kuskanaw for his lodge, Kenneth O’Harra’s tariff sheet and the map in the New York newspaper showing Haines Junction as Kuskanaw give the impression that he hoped to influence the naming of the tiny place that still had no firm name in 1946. The Kuskanaw name did not last because neither did his company, but one can wonder what might have happened had he established a foothold and become an economic player early in Haines Junction’s history.

(New York Daily News, 20 October 1946)

O’Harra’s land file in the national archives indicates that communication with the government ceased for almost all of 1947 and into 1948. The company had continued its Whitehorse-Fairbanks bus service, but its last advertisement in the Whitehorse Star was in late August 1947, and a year later the company filed for bankruptcy.

Kenneth O’Harra acted as receiver for his company and had not surrendered his holdings at Haines Junction, at least in his mind. In April 1949 he wrote to the magistrate in Whitehorse to express his dismay upon learning that “action had been taken to dispose of the O’Harra Bus Lines property known as Kuskanaw Lodge”. The details of this are not known, and the last mention of O’Harra in the Yukon was in March 1950, when he was in Whitehorse to clear up aspects of his bus operation and to withdraw his land application at Haines Junction.

John and Sally Backe

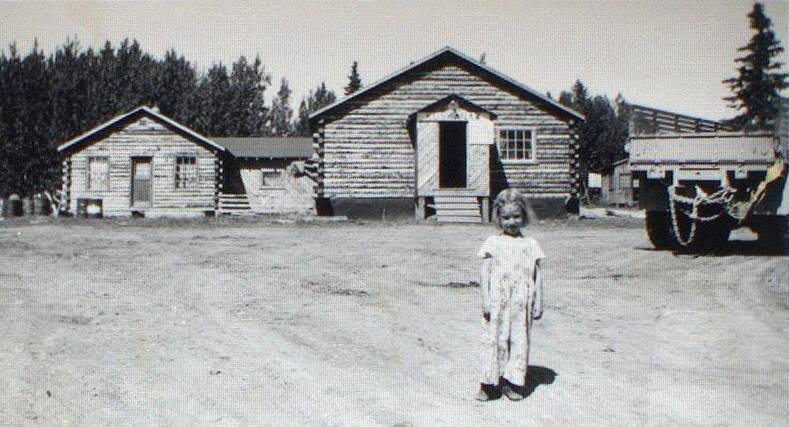

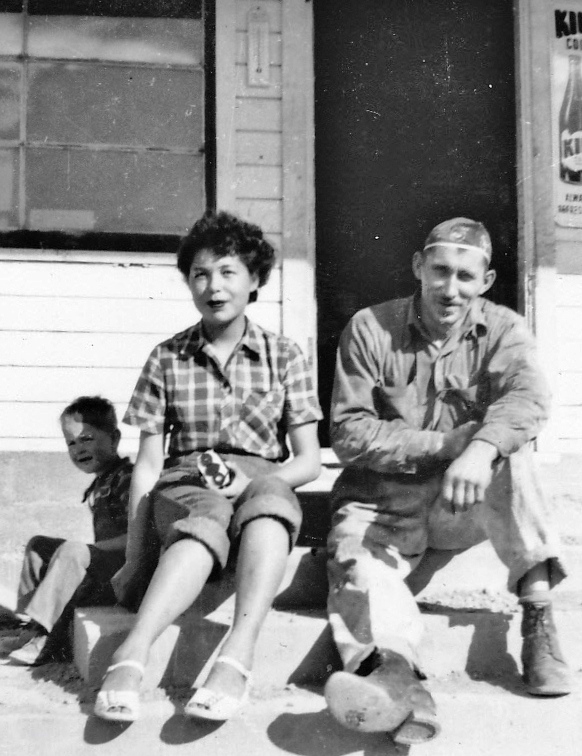

A few of the people who staked and applied for land at Haines Junction followed through on building and operating businesses in the new community. The first were John and Sally Backe, who had immigrated to Canada in the 1920s from Norway and Russia, respectively. John came to placer mine in the Mayo area in the 1930s before marrying Sally Bergen in Vancouver and bringing her to the Yukon in March 1942. After a couple of years they moved from Mayo to Whitehorse and in 1946, with their two young daughters Rosemary and Sally Jr. in tow, they set their sights on an opportunity at Haines Junction.

According to Backe family lore, John and Sally entered into an arrangement with O’Harra Bus Lines to operate a fuel station and rest stop for the bus passengers. John was said to have conducted business on conversations and handshakes, and it is believed that this was a ‘grubstake’ arrangement made with O’Harra to develop and operate its facility.

The Backes set up a hard-walled tent in the summer of 1946 to live in while they helped to build the Kuskanaw Lodge. John also pumped fuel and repaired tires while Sally sold canned goods and made meals. A newspaper article indicates the Backe family may have moved back into Whitehorse for that first winter or part of it.

(Yukon Archives, Bob & Edna Hayes fonds. Acc. 2003/122, #6 – image has been cropped)

A list of services along the Alaska Highway put out in March 1947 showed that Haines Junction had a store, meals, and gas and oil, but no beds. This would have been the Kuskanaw service, being provided by this time by John and Sally Backe because O’Harra had no need of this facility for its Whitehorse-Fairbanks service. It had been planned as accommodation for a bus service to Haines and Juneau that was not destined to happen.

(Yukon Archives, Backe Family fonds, Acc. 2004/70, #4 – image has been cropped)

(Yukon Archives, Backe Family fonds, Acc. 2004/70, #3 – image has been cropped)

The Kuskanaw building became the Backe family’s home for a year or two while they were building a new place for themselves across the highway, where in April 1947 John had staked an acre and a half parcel for a “gas filling station and auto camp”. A spring 1948 photo shows army buildings on this property being put together to form what would become the Haines Junction Inn. The photo indicates that the Haines Junction Inn would not have been ready in time to conduct business during that first summer that the Alaska Highway was opened to tourist traffic.

(Yukon Archives, Jack Abbott Whitehorse Substation Experimental Farm photographs fonds, Acc. 2019/35, #1 – image has been cropped)

A government report of April 1, 1948 showed the available tourist services at Mile 1016 as being a restaurant and gas and oil, which the Backes would have still been providing at the Kuskanaw site. The next year, on March 1, 1949, a government report listed a restaurant, a store, gas and oil, vehicle repairs, and 26 beds for accommodations in Haines Junction, most of which would have been provided by the Backes at their new Inn.

(Yukon Archives, Backe Family fonds Acc. 2004/70, #15 – image has been cropped)

The July 1949 preliminary land survey shows their development to be a 48’x70’ hotel and store building, along with two 20’x20’ garages in the back and three small ‘tourist cabins’. By the following year (1950), when the area was legally surveyed into lots, the Haines Junction Inn was shown to consist of hotel, café, and tavern sections.

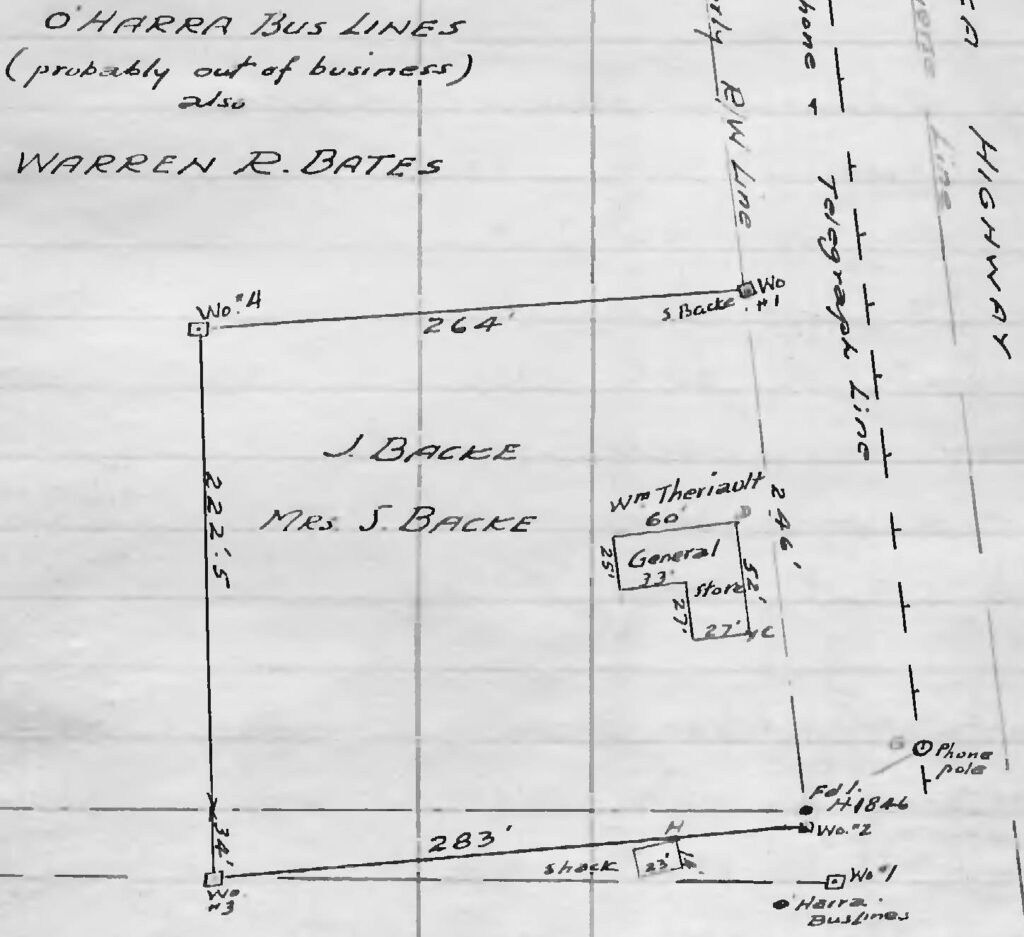

(Canada Lands Survey Records, FB23258, p. 5)

In June 1949, with O’Harra Bus Lines having gone bankrupt, Sally Backe staked an acre and a half of the O’Harra land for a “roadhouse”. The staked land included the Kuskanaw building, which is understood to have been turned over to John and Sally as wage compensation for their role in developing and operating the O’Harra business there. When they moved into their new Inn across the highway, they leased out the Kuskanaw building to Bill and Frances Theriault to operate as a store. The proposed roadhouse on the property Sally staked never happened, but in later years she and John operated a gas station and garage on it.

(Canada Lands Survey Records, FB23258, p. 1)

John and Sally Backe did not wait for things to be done for them to advance their business. In addition to investing time, energy, and money into buildings on land that they did not yet have tenure for, John installed services for the business that also benefitted his neighbors. One was the purchase of two large generators for the Inn, and the excess power was provided to the nearby private residents.

In 1955 John along with Ed Karman, who operated the neighboring Wayside Garage, undertook to dig a sewer line of more than half a kilometer from their businesses to a lagoon of sorts constructed near a wetland area beside the Dezadeash River. This was done with the assistance of an engineer who was working on the Haines-Fairbanks pipeline that was being built through the area. The installation of a private sewer line like this could obviously not happen now, but at the time it served the businesses as well as a number of residences along the route that were able to connect into it.

(National Air Photo Library, A15517, #8)

John and Sally Backe were true entrepreneurs, risking a move from the security of Whitehorse to a tiny spot on the Alaska Highway with an uncertain future. After having two more children, John Jr. and Margaret, when they were living in Haines Junction, John and Sally remained in the community running their businesses for almost all the rest of their lives. Their children continued the enterprise for varying lengths of time for years afterwards.

John died suddenly in Vancouver in 1970 and Sally died in Whitehorse in 1977. Their many community contributions were honored by the naming of Backe Glacier on the east side of Mt. Wood in the St. Elias Mountains, Backe Street in Haines Junction, and the John Backe curling rink in Haines Junction that was built on land he and Sally donated to the town for recreational purposes.

Harvey and Lillian Perrin

Employment on the Alaska Highway brought Harvard (‘Harvey’) Perrin and his wife Lillian north in 1943, and in 1944 twin sons were born to them. At some point they came to the Mile 1016 highway maintenance camp, where Harvey may have been a mechanic. In June 1946 as previously noted, he was an employee of O’Harra Bus Lines, staking the 12.4-acre parcel of land for the company and, along with Lillian, providing meals to the bus passengers.

In September of that year they both staked two 160-acre homesteads to the west of the O’Harra site, but did not follow through with land applications. In the end they did not develop anything more than a tent restaurant in Haines Junction, but must be regarded as early entrepreneurs in the area. .

Lillian was said to be running the restaurant in a large army tent on the western edge of Haines Junction in 1945 and perhaps even 1944, and a story recorded in 1991 establishes that she also did this in the winter of 1946-47. The story was told to the MacBride Museum in Whitehorse by Bonnie Piper, who was staying alone at Mackintosh Lodge while Dorothy Mackintosh was away. The weather had turned very cold, and when it got to -58°C she decided she had to leave, and walked with her dog the six miles to Haines Junction. She stopped at a restaurant in a tent with wooden walls and floor that was being run by Lillian Perrin, where on fancy English china Bonnie was served the best restaurant meal she had ever eaten.

Lillian’s tent restaurant business came to an end in 1947 when she and Harvey and their young sons moved 20 miles east to establish the Canyon Creek Lodge. Tragically, Lillian was killed on Christmas Eve 1955 on her way home from Whitehorse when her car hit a horse near the Takhini River. In 1958 Harvey Perrin sold the lodge to Bob and Emma MacKinnon and lived the rest of his life in Whitehorse, passing away in 1987.

Bill and Bertha Scott

Bill and Bertha Scott were living in Haines Junction by 1945, where Bill was a mechanic at the highway maintenance camp. On April 7, the same day that John Backe staked his land, Bill Scott staked one acre next to him, near the northeast corner of the highway junction. On August 8, he submitted an application for ‘Permission to Occupy’ the land for the purpose of erecting a garage.

More than a year later, while the government was pondering what to do with such applications, an inspection of the land Scott had staked was carried out on September 16, 1948. The land inspector noted that it had no timber because it had been cleared by highway workers for a ball park, and that a small store had been erected and a rough lumber building moved onto the area.

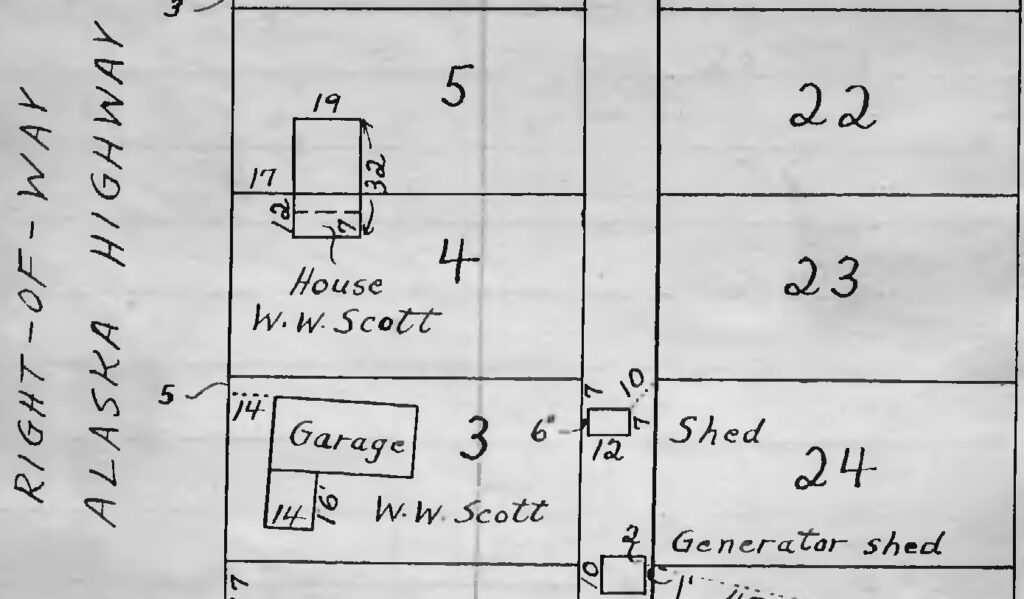

A month and a half later the land supervisor in Whitehorse stated that Scott’s application for Permission to Occupy would be recommended pending a survey of a subdivision there. Bill Scott was already occupying without permission, so it appears that like others, he was not going to let the bureaucratic process hold him up. When the preliminary survey of the Haines Junction townsite was conducted in July 1949, Scott had a 20’x41’ garage erected on the property. By the following fall of 1950 he had a 19’x32’ house built, a 14’x16’ addition on the garage, and two small sheds.

(Canada Lands Survey Records FB23257, p. 4)

Bill and Bertha Scott sold their garage and house to Ed and Betty Karman and moved to Edmonton. In May 1953 he wrote to the government that he wished to withdraw the land application he had made in August 1947. Further information in his land file states that he had sold his rights to the land to William Theriault and Edward Karman, both of whom went on to own the surveyed lots that covered their respective developments.

Ed Karman operated the Scotts’ Wayside garage until it burned down in 1954, but he and Betty remained to spend the rest of their lives at Haines Junction and area. Karman Street in Haines Junction is named in their honor.

Bill and Frances Theriault

Bill and Frances Theriault were in Haines Junction by at least the summer of 1949, when they were operating the general store in the Kuskanaw building under an arrangement with John and Sally Backe. At Christmas of 1949, the store caught fire and Bill and Frances had to carry their two young sons across the highway to the Backes’ lodge. There was no fire department, so the available people in town formed a bucket brigade, but the store burned down and the Theriault family had to stay for a time with the Backes.

By June 1950 Bill and Frances had a new 20’x48’store building in place next door to Bill Scott’s garage, on the northeast corner of the highway junction on land that Scott had staked. The Theriaults had enlisted the help of Bun Beloud, who had a highway lodge at Dezadeash Lake on the Haines Road, to haul in old army buildings to create the store.

(Canada Lands Survey Records FB23257, p. 4)

The Theriaults named their business the Fairdale Store and it included a post office, with Frances becoming Haines Junction’s first postmaster in July 1950, and living quarters in the back. The Theriaults operated the store for another eight years before selling it in 1958 to Al and Gloria Allison and moving to Vancouver Island.

(Hugh Bradley collection)

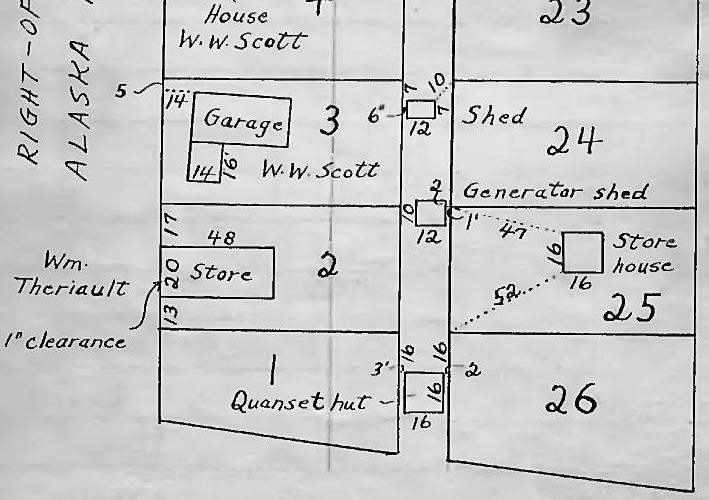

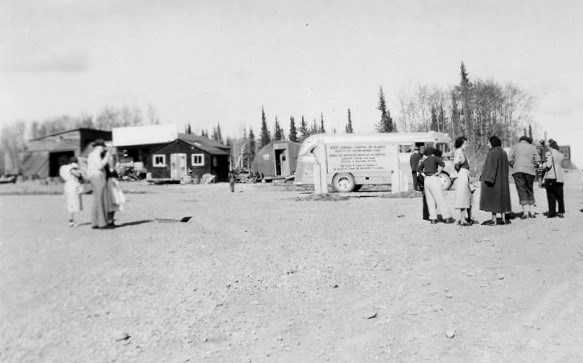

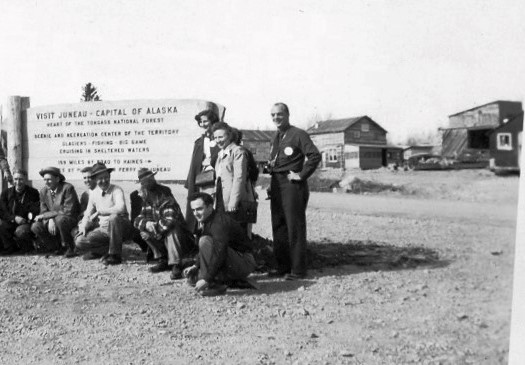

The Fairdale Store, the Scotts’ house and garage, and a bit of the Backes’ lodge were captured in June 1950 photographs taken by RCMP Cst. Art Deer when he was stationed at Haines Junction. The photos of a group of people from Juneau at the highway intersection provide a rare view of some of these early business-related buildings that had been erected or placed there within the previous two years. The details of these photos are provided in the captions.

(Bertram Arthur Deer collection)

(Bertram Arthur Deer collection)

Rusty and Genevieve Martin

Royal Canadian Mounted Police members are generally transient in small communities, but Cpl. Rusty Martin seemed to have a little more attachment to Haines Junction. He was posted to the community in 1945, where in 1947 he married Genevieve Kenny. By the summer of 1949 they had put up a 25’x32’ house and 12’x14’ garage beside the Haines Road, about 600 feet south of the highway intersection.

(Canada Lands Survey Records FB23257)

A small building known as the ‘Rusty Martin cabin’, which was likely his garage, was moved next to the Fairdale Store sometime by 1956. There it was used and looked after by all the store owners over the years, gradually becoming an unofficial heritage building until the Village of Haines Junction took over the property and removed it. Martin Street in Haines Junction is named for Rusty Martin.

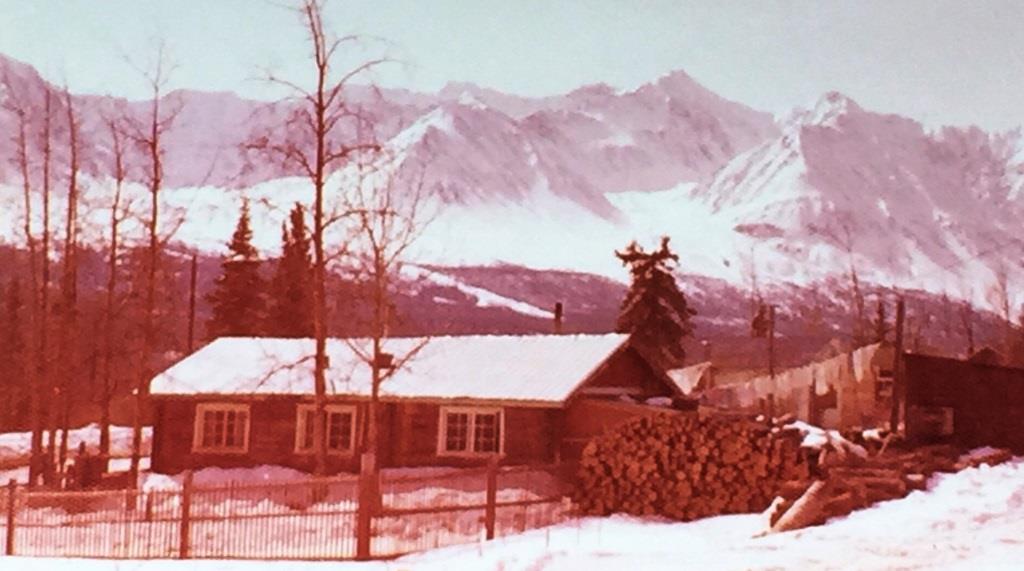

(Gord Allison collection)

Dave and Hazel Hume

Dave Hume and Hazel Pringle were born and raised in the Shäwshe (Dalton Post) area and married in 1939. They had a large family by the time they, along with Dave’s father and Hazel’s mother, moved to the community of Haines Junction. Dave had previously worked on the building of the Haines Road and then in the latter 1940s took employment as a heavy equipment operator at the Haines Junction highway maintenance camp.

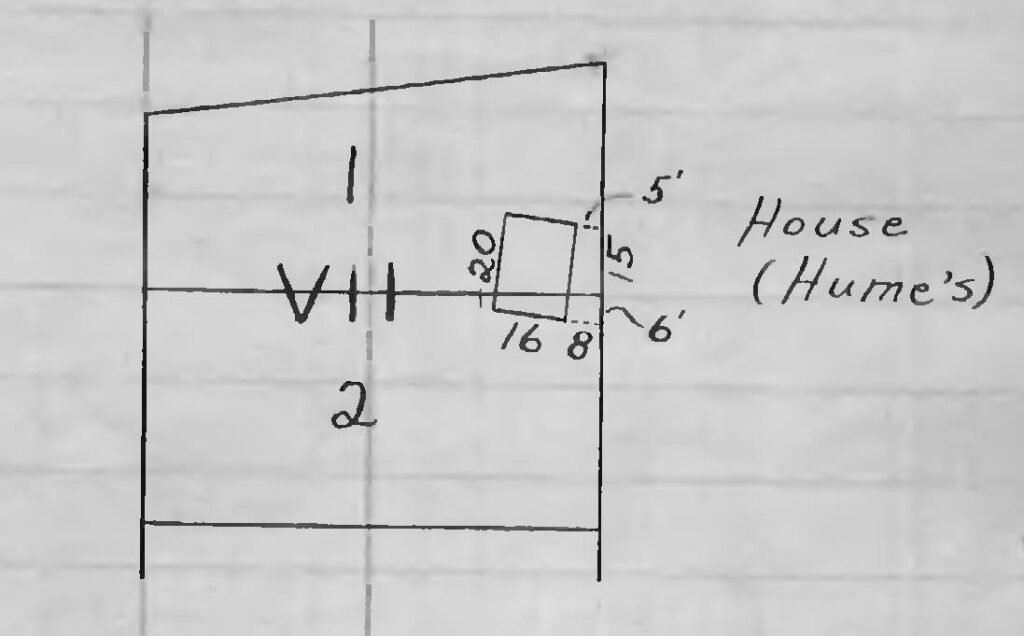

The family established itself in an area on what was then the west edge of the town, to the west of the Kuskanaw Lodge site. The 1950 survey shows that they had a 16’x20’ cabin on their property at that time, but more buildings were soon to follow to accommodate the family as well as the elderly parents.

(Canada Lands Survey Records FB23257, p.7)

(Gord Allison collection)

Dave and Hazel Hume continued to live in Haines Junction until Hazel died in Whitehorse in 1968 after a lengthy illness. Dave went on to have another family and passed away in Whitehorse in 1996. Most of his and Hazel’s many descendants remain in the Haines Junction area. Hume Street in the community is named for Dave and Hazel Hume.

Pete and Mary Eikland

Pete Eikland came from Norway as a teenager in the early 1900s and ended up in the Beaver Creek area. He married Mary, who was living in a First Nation village on the Yukon-Alaska border, and they had five children together. Their son Charlie said that when they were living in Snag, Catholic Church officials would occasionally come and try to get the kids to go to residential school. To avoid that possibility, Pete and Mary moved the family to Haines Junction in 1949 so the kids could go to school at the Army camp.

They first moved into what Charlie termed a shack at Mickey Blackmore’s sawmill site a mile and a half north of the community, from where he and his sister Nellie walked to school. Pete staked land in Haines Junction along what had been the pioneer road, about 800 feet east of the highway intersection, and had an 11’x11’ building on it at the time of the 1950 survey. He later built a log house that the family lived in until 1955, when they moved back to Beaver Creek. Most of Pete and Mary’s descendants still live in the southern Yukon, some in Haines Junction.

(Canada Lands Survey Records FB23257, p. 10)

(Roberta Allison collection)

Haines Junction Milestone Developments after 1950

A number of events at various times after the first town lots became available for purchase influenced the growth and development of Haines Junction. There were many that could be listed, but the more significant ones were:

- 1954 – the Haines – Fairbanks pipeline, including the Mile 1026 pump station

- 1960 – the resettlement of First Nation people to new housing on the east side of Haines Junction

- 1972 – the establishment of Kluane National Park & Reserve

- 1995 – the Champagne & Aishihik First Nations Final and Self-Government Agreements

Ending

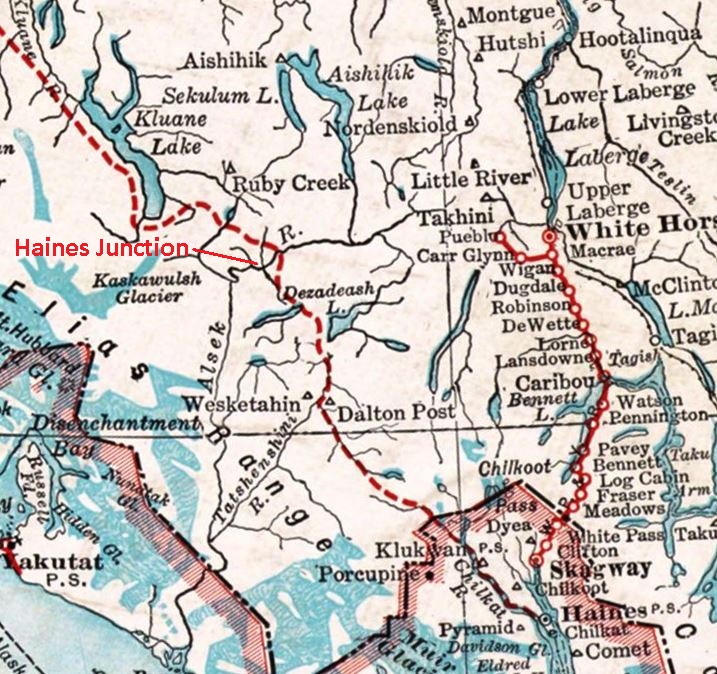

Haines Junction was not at a natural place for a Yukon community to develop. It is not at a strategic point on a waterway or in a mineral-rich area, but a number of factors related to roads fell into place for it to happen. The summer route of the Kluane Wagon Road through the site determined the route of the pioneer road, which determined the route of the Alaska Highway. The spot that became Haines Junction resulted from two highway routing decisions, the location of the Haines Road crossing of the Dezadeash River and the abandonment of the Bear Creek Cut-off that would have bypassed the site of the future town.

The highway junction that resulted led to the founding of the community, and the economic opportunities, particularly in the travel, tourism, and service sectors, kept it growing. Once firmly established, the natural beauty and recreational values of the area along with the spirit, volunteerism, and hard work of early residents to make it a good place to live attracted others to come and do the same. The result has been 80 years so far of a place where people have chosen to live some or all of their lives.

Acknowledgements

Many people who were involved in the early development of Haines Junction still have a presence in the community in terms of descendants who are either still here or retain a sentimental connection to this place, even from afar. A number of people in both categories have contributed to this article.

I would like to thank Sally Hogan, Rosemary Gute-Greuning, John Backe, Charlie Eikland, Tom Eikland, Carol Buzzell, and Nora Martin for their family information. Bill Karman, Phil Bastien, Brad MacKinnon, and Rod Watson also contributed knowledge and information about early Haines Junction. The Backe family, Tom Buman, Mark McPherson, Peter Deer, Nora Martin, and Brian Langevin contributed photos.

Previous work has recorded some of the history and stories of Haines Junction’s beginning and growth. The first was Ellen Harris’s paper called “A History of the Development of Settlements in the Shakwak Valley Area”, written for a university course in 1981. Ellen was a school teacher in the early 1950s at Haines Junction and her paper contains a wealth of information, much of it from interviews and conversations with old-timer informants about the early history of the community and area. Her paper can be found at the Yukon Archives.

In 2007 some of the history of Haines Junction and the area was compiled in a book of stories called From First We Met to Internet: Stories from Haines Junction’s First Sixty-Five Years as a Settlement, 1942-2007. This informative and entertaining book was a History Project produced by the Haines Junction Campus of Yukon College. The driving force behind the project and the book was its designer, coordinator and editor, Elaine Hurlburt. It is available at the Yukon Public Library.

Updated January 3, 2024