The Kluane Wagon Road – part 2

Building of the Kluane Wagon Road

All the new developments in the Kluane region required the support of a good road, and it wasn’t only the miners who needed the access. In the summer of 1904, R.G. McConnell of the Geological Survey of Canada visited the region and observed that more than anything else, the high transportation costs were retarding development.

At the same time, the Yukon was in the early stages of decline with the Klondike goldfield returns waning. The promise of Kluane gold was the impetus needed to stimulate the economy, despite the unproven economic potential of the region. The Yukon government realized that the new mining activity called for an investment in exploring a route for a wagon road to bring down the transportation costs, to assist in the development of mining interests, and to link small communities with the supply center of Whitehorse.

This view was not held by everyone, however, and due to some opposition from Dawson City-based politicians, the funds were not approved until mid-August of 1904, and construction work did not commence until the late summer. The nature of the initial work is not clear, but some of the expenditure was engaging the land surveyor Henry Dickson to assist Territorial Engineer William Thibaudeau in locating the new road.

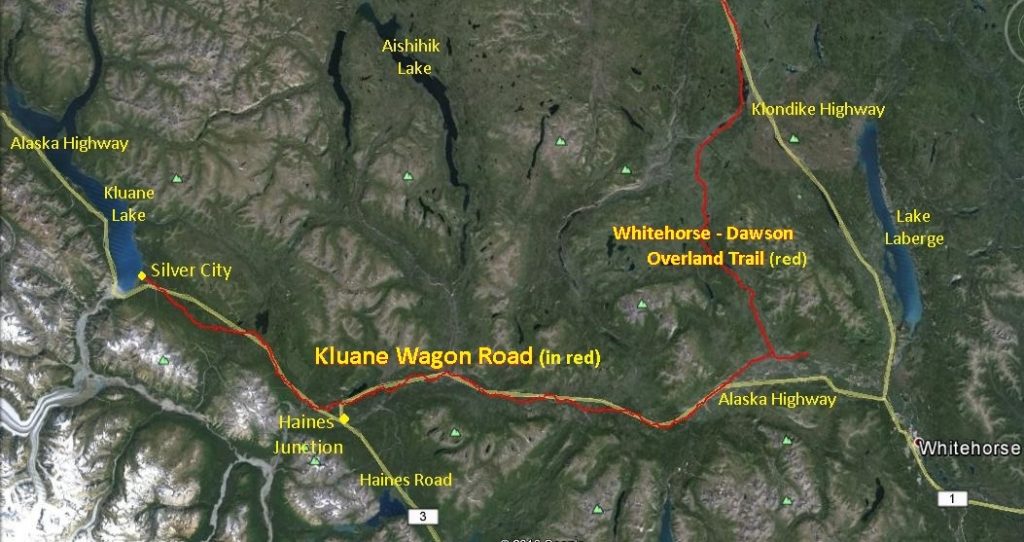

Construction of the Kluane Wagon Road (KWR) was started by branching off from mile 32 of the Whitehorse-Dawson Overland Trail, northwest of Whitehorse. The Overland Trail had been constructed two years previous, in 1902, going northwest from Whitehorse to the Klondike goldfields and Dawson City. The KWR headed westward, following the Takhini, Mendenhall and Dezadeash River valleys, then passed over the Bear Creek summit before eventually terminating at Silver City, near the south end of Kluane Lake.

(Google Earth)

The bulk of the roadwork was completed during the fall and winter of 1904-05 with construction of 81 miles of the road and a 5-mile winter road branch to Ruby Creek. In addition to clearing of trees and brush, construction involved corduroying of wet areas, placement of bridges and culverts, and cutting of the roadbed into hillsides where required. Evidence of sidehill cutting, which involved considerable manual labor and work by horse-drawn equipment, can still be seen at many places along the KWR.

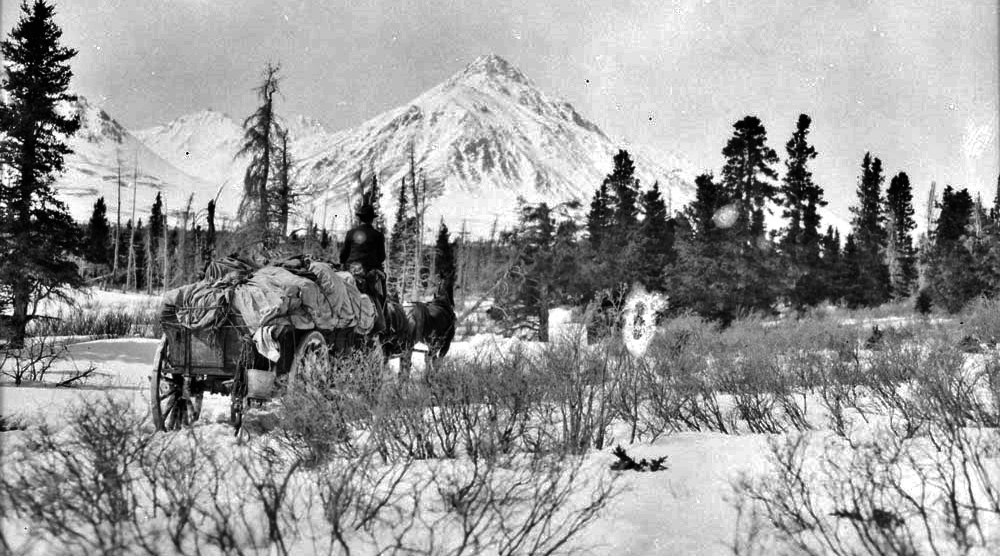

The eventual course of the wagon road was determined by the need to accommodate horses pulling wagons and sleighs, for which the routes used for foot and horseback travel were inadequate in many places. The relatively crooked nature and greater length of the KWR compared to the present-day Alaska Highway show that the wagon road was located to avoid obstacles such as wet areas, gullies, sidehills and steep hills as much as possible, particularly the latter.

(Yukon Archives, E.J. Hamacher fonds (Margaret and Rolf Hougen collection, #837) – photo has been cropped)

It appears that milepost markers were placed along the KWR, as some applications for land along the road have accompanying sketches that show mileposts, as does at least one land survey near the road. The markers showed the mileage from Whitehorse, so would have included 32 miles of the Whitehorse-Dawson Overland Trail. I have not come across any remaining such markers on my traverses along the road and so do not know what they may have looked like.

Related Developments

On the heels of construction of the KWR came the establishment of roadhouses to serve travellers. Nine hotel liquor licences were issued for new Kluane area establishments and newspapers carried advertisements for establishments such as the Kloo Lake Hotel and Restaurant and services such as the Bullion & Ruby Transportation Company. At least 10 roadhouses were built, and land applications were made for others that never came to fruition. Most of these establishments were relatively short-lived as the mining activity declined in the next few years, but two of them, at Champagne and Bear Creek, persisted more or less continually for the duration of the KWR’s existence.

(Yukon Archives, Claude & Mary Tidd fonds, #7221 – photo has been cropped)

Very soon after the gold discoveries in 1903, the White Pass & Yukon Route began using small sternwheelers on the Takhini River to haul freight and passengers from Whitehorse. This eliminated about 50 miles of the wagon trail, which then was still quite primitive. In 1904 the company announced that it would be placing feed and building stables at the confluence of the Mendenhall and Takhini Rivers for a freighting and stage business to the Kluane goldfields. A small community called Mendenhall Landing (also called Steamboat Landing) sprang up, consisting of a roadhouse, buildings to store freight, and cabins.

In 1904 at what was to become the community of Burwash Landing on Kluane Lake, the brothers Louis and Eugene Jacquot from France established a trading post and store. This followed the discovery of gold on nearby Burwash Creek in May of that year and a promising discovery the previous fall on Bullion Creek, near the south end of the lake. The Jacquots later were involved in the big game outfitting business as well. In 1920 they rebuilt the original log bridge at Canyon Creek, the most visible and enduring remnant of the KWR.

Use of the Kluane Wagon Road

(Library & Archives Canada, #PA-044670)

With disappointing gold returns, the promises of the Kluane region did not materialize and by 1907 the mining activity settled down to a much lower level and would remain that way for the years to come. Miners continued to use the KWR, as did the roadhouse operators to haul supplies from Whitehorse and other people for various purposes. This included government services such as the mining recorder and post office, as well as the Northwest Mounted Police. Harry Chambers of Champagne provided mail carrier services, and later his son George did the same when automobiles were in use.

The 1910’s saw the introduction of a new industry into the southwest Yukon, the hunting of big game. The hunting parties used the KWR during the decades to follow, first using wagons and then automobiles later in the 1920’s. Some of the hunters provided accounts of their use of the KWR. Harry Auer described on his trip in 1913 how “…the transport [wagon] sank in the clay up to the axles within three hundred feet of the [Boutellier] summit …”, requiring them to unload the wagon and carry the contents on their backs to the top. G.O. Young described in his 1919 trip account how Louis Jacquot of Burwash Landing, with his six-horse team pulling a wagon loaded with 5,500 pounds of supplies, would cut a spruce tree, leave the branches on and chain it to the rear axle to act as a brake going down steep grades.

One story of the hazards of travel on the KWR is that of Frank Sketch, who had been a horse wrangler on Young’s hunting trip. Sketch was involved in freighting for the Jacquot brothers and on a trip from Whitehorse the log bridge over the Mendenhall River gave way under the load. In the chaos he was kicked in the face by one of the frantic horses and ended up losing an eye, and one horse drowned as well. Sketch was sent on a spare horse to Steamboat Landing for help, while the other two freighters returned to Whitehorse to replenish the winter’s supply of provisions that had been lost.

The first automobile to travel on the Whitehorse-Dawson Overland Trail was in December 1912, and so it is reasonable to assume they began to be used on the KWR not long after that. Frances Kipp, a nurse sent to Champagne in 1919 to assist with the influenza epidemic, described her trip from Whitehorse in an open Ford vehicle. She and her travel companions had to fill holes in the road and clear brush and fallen trees, taking them eight hours to make the 64-mile trip.

A 1920 photograph in the collection of Frank Harbottle, who operated a small transportation line between Whitehorse and Kluane Lake, includes information that the Bear Creek roadhouse, which was six miles west of Haines Junction, was the exchange point from automobiles to horses and wagons. After a vehicle bridge was built across the Jarvis River in 1923, “Kluane Lake … [could] be reached in comfort by automobile”.

(Yukon Archives, Ryder Family fonds, #354 – photo has been cropped)

Undoubtedly the longest-lasting users of the entire length of the KWR were Eugene and Louis Jacquot of Burwash Landing. They transported supplies from Whitehorse along the wagon road for the operation of their trading post, roadhouse and store from 1904 until the Alaska Highway came through in 1942. In a book by G.O. Young about his hunting trip in 1919, he mentions that “all along the route we saw signs of Louie Jacquot’s skill as a teamster.”

In a conversation with late Kluane First Nation elder Josie Sias (nee Jacquot), she recalled trips from Burwash to Whitehorse by both buckboard and automobile as a young girl. By both modes the trips took 7-10 days each way (15-20 miles per day), and three trips per year were made for supplies for the Jacquots’ facilities at Burwash. She remembered the trips as a fun time, bouncing along on a mattress in the back of the truck and camping out along the way.

Life in the Kluane region did not change as dramatically with the KWR as it did later with the Alaska Highway. Moose Jackson, a late elder of the Champagne & Aishihik First Nations, said that the wagon road didn’t mean much to First Nations people at first; it was just a bigger horse trail. The use of the KWR by First Nation people is indicated by brush camp structures that have been found in proximity to it. Moose said that eventually some First Nations people acquired automobiles for use on the KWR before the Alaska Highway came through.

Next: Part 3 – Legal Survey, Retracing, and End of the Kluane Wagon Road