The Swinehart Farm – part 5

The Swinehart Farm today

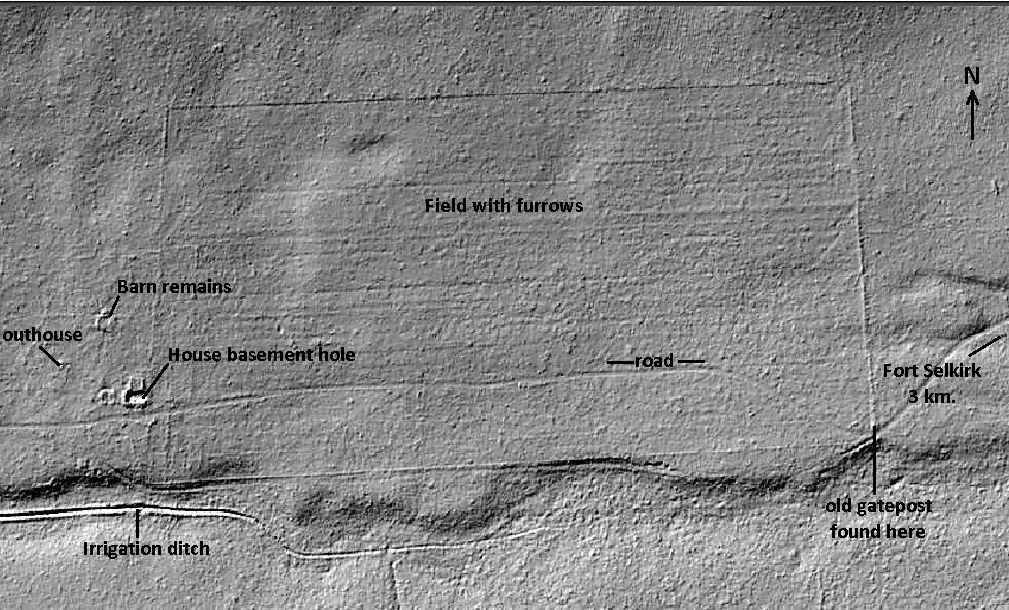

So what of the Swinehart Farm site now? The three-kilometer bush road from Fort Selkirk to the farm provides a pleasant walk through an open mixed forest of white spruce and trembling aspen. It is very easy not to notice the subtle change at the farm’s eastern boundary to a more open forest of fairly large aspen trees with a lesser component of spruce. A closer look near the boundary line shows a line of large aspen trees all leaning westward at the same angle. Beside this, faint furrows discernible in the ground along the line of trees reveal this to be the eastern edge of a field. Nearby are the remnants of a gate post lying rotting on the ground.

(©Gord Allison photo)

A fairly deep hand-dug ditch along a low area just to the south of the road is easy to miss due to willow growth, and impossible to see when the leaves are out. Further along beside the road is a large hole in the ground with cribbed walls that was the basement of the farmhouse, and rotting sill logs on top of the ground show an extension or addition to the house. I have been told that the house was cut up for firewood and taken to Fort Selkirk many years ago.

(©Gord Allison photo)

A short distance from the house site, more rotting sill logs visible only as lumps under the surface vegetation mark the outline of what was probably the barn, judging from the old photographs. Scattered around the house and barn area are old tin cans and other debris, as well as a few homemade metal and wooden objects of unknown function. Nearby is a log outhouse, the only remaining standing structure at the farm.

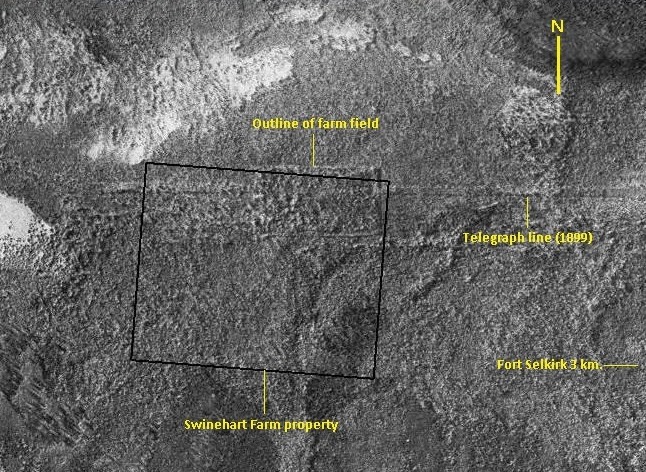

The entire Swinehart Farm field has grown back to forest, presently in a mature aspen successional stage. When on the ground at the farm, the surrounding hills cannot be seen above or through the forest, particularly when the trees are in leaf. However, the former cultivated field is still quite visible on air photographs more than 100 years after the farm was abandoned. Similarly, the clearing for the telegraph line that was built in 1899 still shows up from the air all these years later.

(Yukon Lands Viewer)

Physical evidence of the Swinehart Farm became very apparent when the area was included in coverage using the technology called LiDAR (‘Light Detection and Ranging’) in 2020. This tool shows the earth’s surface as if there was no vegetation, enabling past human activities on the landscape to be seen.

(Yukon Government LiDAR collection)

The setting that was a home for several people more than 100 years ago has now gone back to nature and sees very few people. The daily life and activities that occurred there for 16 years can now only be imagined amid the silence and regrowth of trees. Only a few remnants persist as evidence of the farm, with the hand-dug irrigation ditch that runs for hundreds of meters remaining as the most visible testament to the industriousness of the Swinehart family and others that worked there.

(©Neal Allison photo)

Oral history projects conducted at Fort Selkirk in 1984 and 1985 revealed some knowledge of the Swinehart Farm and family. The participants knew of the farm and had been at the site before, mostly after it was abandoned. In 1985 interviews, Selkirk First Nation elders Charlie Johnson and Tommy McGinty said that Swinehart raised chickens, hay and vegetables at his farm.

In her 1984 interview, Martha Cameron said that in Dawson City as a young girl she spent time with Leta (Swinehart) Stillman, who taught her how to sew and make clothes. She also knew Guy Swinehart and told of having to make him lunch one day and he asked her to cook two dozen eggs, then ate them all. In the 1930’s and ‘40’s when Martha was married and lived in Fort Selkirk, she and other ladies and their children went on picnics out to the abandoned Swinehart Farm area.

More than 30 years after Martha’s interview, her daughter Ione Christensen also recounted her memories of those picnics as a young girl in the 1930’s at the little lake beyond the Swinehart Farm. Ione remembered going past a house with a veranda, which fits with pictures of the Swinehart farmhouse. She said nobody lived there then and no one in Fort Selkirk at that time had known the Swinehart family.

The ownership of the Swinehart Farm remains a curiosity, as the title is still in the name of the original holder, Frank Bach, who died in 1933. More than 100 years after the death of William Swinehart and abandonment of the farm, the land taxes are still being paid and the property “is under the care of Curtis Bach”. This enduring private ownership of the property resulted in its exclusion from the surrounding Selkirk First Nation Settlement Land and the road to it being surveyed out to maintain legal access.

The reason that the Bach family continues to pay the property taxes and hang on to this piece of Yukon bush is their business, but it is intriguing nevertheless. There are still members of the Bach family living in Juneau, one of whom told me he has been well aware of the property all his life and feels connected to it, even though he has never been there.

The pioneer Swinehart Farm and family played an important role for a number of years in the Fort Selkirk community as well as in early Yukon agriculture, but that seems to have become forgotten over time. Hopefully the farm and the family can regain some awareness and recognition of their place in Yukon history.

(Heather & David Ingrams collection)

Updated October 7, 2023

Just confirming that that is definitely my great grandfather, Rev. John Hawksley!

Courtney Green Talty, granddaughter of Gladys Hawksley, the youngest of John Hawksley’s children.

Thank you for this confirmation. I have come across his name a number of times in my research, particularly in the Fort Selkirk area of the Yukon.