The Murder Plot

George Andrew Martin Lane O’Brien was born in 1864 in Jersey in the British Channel Islands. He had an older sister and younger brother and by 1881 they were living in Birmingham, England, where 16-year old George was listed as a blacksmith.

In 1888, at age 24, O’Brien was charged with “feloniously shooting … with intent to murder” and was found guilty of “inflicting grievous bodily harm with intent to rob”. He was sentenced to seven years in penal servitude at Dartmoor Prison in southwest England and released in 1894.

It is not known when O’Brien came to Canada and to the Yukon, but one piece of information places him in Dawson City by May 1898. In that month, O’Brien suggested to a man named Chris Williams that they should work together in robbing travellers on the river trail, as people were sometimes known to carry a fair amount of gold and/or cash with them. The plan included murdering the victims and disposing of their bodies under the ice. This partnership did not materialize.

O’Brien was arrested in Dawson City in September 1898 for theft and was put to hard labor on the NWMP woodpile. He broke out in December and was recaptured later that same month and given an extra six months for his escape. While in jail he suggested the same robbery and murder plan to a fellow prisoner named George West, a career criminal from Washington who went by the moniker of Kid West. He also did not take O’Brien up on the offer. O’Brien’s solicitations to Williams and Kid West make it clear that while robbery was his motive, murder was part of the plan.

O’Brien was released from jail on September 16, 1899 and ordered to leave the Yukon as an undesirable. At some point while in jail or after his release, he partnered up with a man named Thomas Graves. Other than that he may have been an Englishman, little is known about Graves or even if that was his real name.

O’Brien and Graves meet Constable Pennycuick

O’Brien and Graves started south from Dawson City on the river trail in late November or early December, staying at some of the roadhouses and stopping places along the way. With them were two dogs they had stolen in Dawson, a big yellow and white St. Bernard type and a smaller black dog.

O’Brien and Graves were not physically distinctive enough that people could later remember them, and registers at the establishments were not reliable. However, people remembered where and when they saw the big yellow dog, an unusual type for the Yukon at that time. Between December 5th and 11th, an operator of a stopping place between Fort Selkirk and Old Minto saw a man with a big yellow dog several times, including when the man tried to sell him some canned milk.

An investigation into the cache thefts by NWMP Constable Alick Pennycuick, stationed at Fort Selkirk, led him to finding O’Brien and Graves on December 11th. They were at a camp near Hell’s Gate, a bad section of river for riverboats located 10 miles south of Fort Selkirk. They gave their names as Miller and Ross and said they were prospectors. This meeting caused Pennycuick to view the two men as suspects and was the beginning of a chain of events that would establish his reputation as an investigator.

The encounter with O’Brien and Graves displayed at least one example of Pennycuick’s observation skills. During his questioning of the men, he noted an odd double set of damper holes that formed a figure-eight punched in the stove pipe, and he even made a sketch of it. This observation was to prove very helpful a few weeks later.

On December 14th, Pennycuick received a warrant for the arrest of the two men for things they were suspected of doing previously north along the river trail. When he went to their camp to arrest them, they were gone. However, more complaints of thefts came in, leading Pennycuick to believe O’Brien and Graves had not gone far.

Setting the Stage for Murder

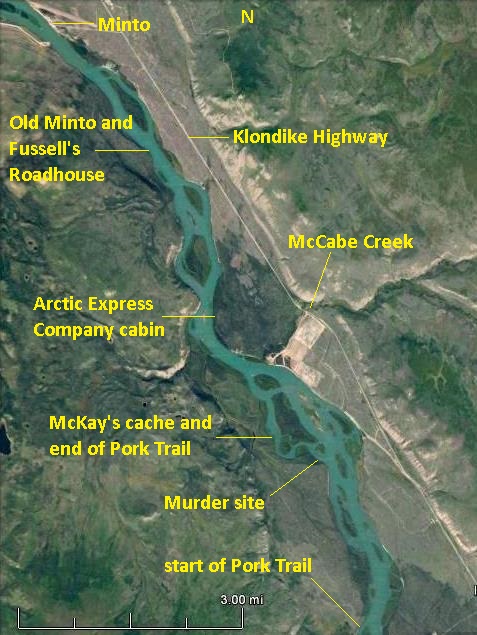

O’Brien and Graves left their Hell’s Gate camp not long after Pennycuick’s visit, turning up late in the evening of December 12 at Fussell’s roadhouse at Old Minto. Like other people, John and Agnes Fussell remembered the big yellow dog that accompanied the men.

From the roadhouse O’Brien and Graves moved two miles south and occupied an abandoned cabin on the east side of the river. It was called the Arctic Express Company cabin because it had been built by a short-lived mail and express service enterprise. The two men stayed there for several days and were engaged in stockpiling supplies they had stolen from caches. Once again, they were identified at this location by the presence of the big yellow dog.

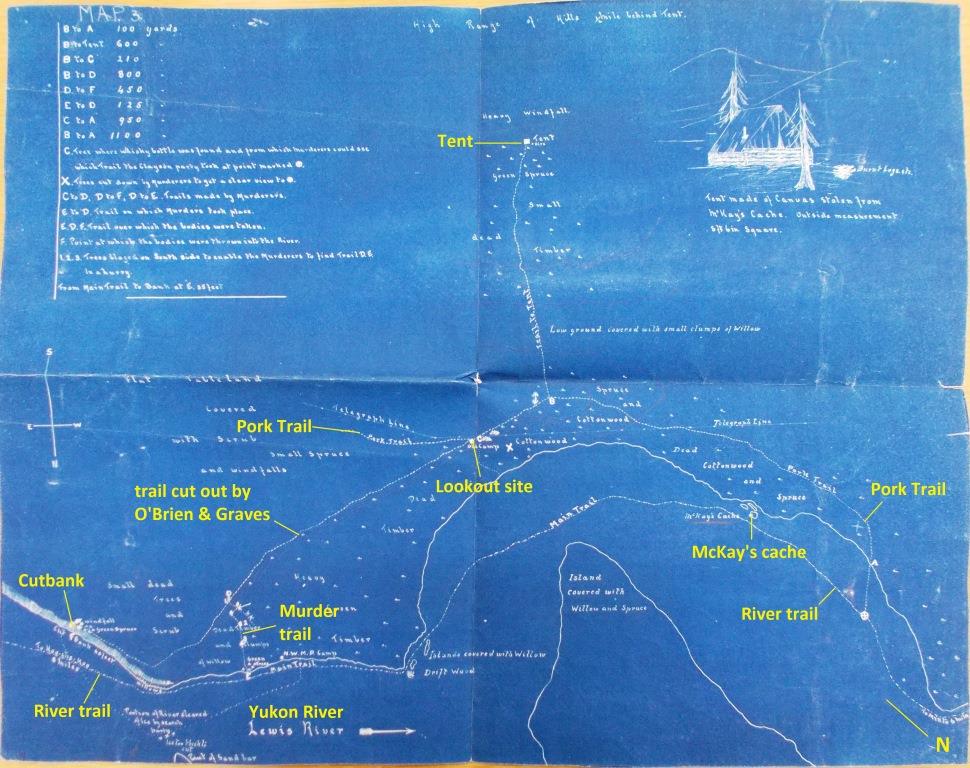

A few days later O’Brien and Graves moved further south, this time 2½ miles and to the opposite (west) side of the river, nearer to McKay’s cache that they were now looting. From the river trail they went about 1,100 yards up the Pork Trail, then cut out a new trail 600 yards into the bush. There they constructed a tent made of an 8½ foot square log frame covered with a canvas roof and moved themselves and their stolen goods into it. It was now just a few days before Christmas.

(Google Earth)

O’Brien and Graves cut out more trails to carry out their robbery and murder plan. From an old campsite a ways south along the Pork Trail, they cut a trail 1,250 yards eastwards that ended on the top of a cutbank by the river. A short distance before the river, they cut another trail that branched off and went 125 yards out to the river about 500 yards north of the cutbank. This short piece of trail was where the murders were to be carried out. Not far away from the cutbank was an open hole in the river measuring 6 feet in width and 30 feet long.

(Library & Archives Canada, RG18 Vol. 254, File 318)

(Google Earth)

Back at the old campsite, which was situated on an elevated bench, O’Brien and Graves made a lookout spot by cutting down 27 trees out to the river. This allowed them a view all the way to the junction of the river trail with the Pork Trail so that they could see when somebody was coming, which trail they were taking, and possibly who it was. Perhaps for this purpose alone, O’Brien had field glasses (binoculars), an uncommon item to be packing along the trail. The stage was set for the right victim(s) to come along.

(Library & Archives Canada, RG18 Vol. 254, File 318)

Clayson and Relfe Leave Dawson

Frederick Hughes Clayson was born on June 1, 1872 in Port Madison, Washington, the fourth of six children. His father, an English seaman who had jumped ship in Seattle in 1864, was a well-known newspaper man but also a bit of a scoundrel who had public battles with his estranged wife. Despite this or perhaps because of it, their children did well for themselves, with one of them, Esther Pohl Lovejoy, becoming a renowned obstetrician, global public health advocate, and writer.

Frederick and his older brother William went north with the Klondike Gold Rush, taking with them a huge cargo of merchandise, including all the shoes they could buy in Portland. They started a store in Skagway called F.H. Clayson & Co. Outfitters. Frederick made periodic business trips to Dawson City in 1898 and 1899, and one report said that he bought gold while there. He made his last trip to Dawson in early November 1899.

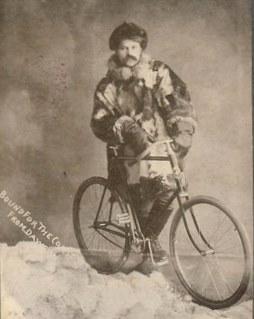

On December 15, while O’Brien and Graves were engaging in their shady activities almost 200 miles to the south, Frederick Clayson started south along the Yukon River trail from Dawson on a bicycle. He was bound for Skagway to rejoin his brother William in the family business there and expected to travel fairly quickly on the hard-packed trail.

(Ancestry.ca – Fletcher/Clark Family Tree)

Linn Wallace Relfe was born on May 19, 1876 in St. Louis, Missouri into a prominent family, his father being a state legislator. Linn was the only son and had two sisters. By 1890 the family had moved to Seattle, where Linn’s father was an attorney and became the police commissioner.

Linn was very close to his father and by the age of 16 was working with him as a clerk in an abstract and title guaranty company. By 1894, Relfe Sr. had started his own legal firm and Linn worked for him there as a stenographer, then in 1895 was working as assistant secretary at the Chamber of Commerce. He was said to be a well-known and popular young man in Seattle, with a wide circle of friends.

Linn appeared to be following a similar path as his father when Relfe Sr. died the next year at the age of 56. However, before settling down to that sort of career Linn undertook a Klondike Gold Rush adventure. He departed Seattle in August 1897, expecting to make it to Dawson City by September 25.

Linn was a good son, writing letters to his mother along the way. On September 6, he wrote that after coming over the White Pass from Skagway, he was within 13 miles of Lake Bennett and far ahead of the large crowd of goldseekers. He presumably made it to Dawson City that fall, and reports over the next two years have him working as a gold weigher, a bookkeeper, a cashier and a bartender. In October 1898 he made a trip back to Seattle for a visit with his mother and sisters. A little over a year later he planned another trip home to Seattle, but this time he would not make it.

Linn Relfe left Dawson on foot on December 16, the day after Clayson, travelling lightly with only a small pack. He was also heading south for Skagway, where he would get on a boat for Seattle to visit his family.

A couple of days after departing Dawson, Relfe caught up to Clayson, who had broken a pedal on his bicycle and was walking it along. The two men travelled together for most of the next week and at their stop for the night in Fort Selkirk on December 21, Clayson wired his brother to expect him in Skagway on December 28.

Clayson pushing his bicycle and Relfe on foot arrived at Fussell’s roadhouse at Old Minto in the late afternoon of Christmas Eve. They had travelled 196 miles from Dawson and settled in for a good night’s rest before resuming their trip southward on Christmas Day.

Olsen’s Christmas Invitation

Almost nothing is known about Lawrence Olsen other than he was a lineman on the Yukon telegraph line and, according to one newspaper article, was a Norwegian. Another newspaper article said that at the time of his disappearance he was owed six months’ wages, so he may have been part of the telegraph line’s construction crew and took a lineman job after it was completed. He was viewed by Cpl. Ryan of the NWMP at the Hoochekoo post as a steady man.

On December 22, Olsen headed north on foot from the Five Fingers telegraph station to find and repair a break in the line or whatever was interfering with the telegraph service to Fort Selkirk, the next station 56 river miles away to the north. After about 16 miles Olsen had not encountered the problem and stopped at the Hoochekoo NWMP post to overnight with Cst. Patrick Ryan. Ryan had invited a couple of local woodcutters for Christmas dinner and extended an invitation to Olsen, who accepted and said he would be back on Christmas day.

The next day, farther north near Old Minto, Olsen located and fixed the telegraph line issue with the assistance of a NWMP member from the Fort Selkirk post. As it was late afternoon they went to Fussell’s roadhouse to spend the night before heading back to their home bases. It was Christmas Eve and also at the roadhouse were the two river travellers from Dawson, Frederick Clayson and Linn Relfe.

Christmas Murder Day

After breakfast at the Fussell roadhouse on Christmas morning, Clayson, Relfe and Olsen left together and proceeded southward. Olsen invited Clayson and Relfe to join in the Christmas dinner at the Hoochekoo NWMP post. It was only a 16 mile trip, so it should have been a relatively easy four to five hour day of travel.

About six miles from the roadhouse, O’Brien and Graves were waiting at their lookout point when they spotted potential targets coming along the trail. There is no information to indicate that O’Brien and Graves knew who these men were, so they likely made the decision at that moment. They may have thought three people to be optimum because collectively they might have considerable valuables on them, and that number of people would be ‘manageable’.

O’Brien and Graves went to lie in wait and when Clayson, Relfe and Olsen drew near, they were accosted at gunpoint and forced onto the 125-yard trail that O’Brien and Graves had cut out. With thick brush to hinder escape, it took only a minute or two for this short stretch of narrow trail, termed Death Alley by one newspaper, to become the execution place it was intended to be.

(Library & Archives Canada, RG18, Vol. 254, File 318)

The bodies were stripped of the clothing that may have contained valuables and then hauled up a bank, probably in the sled pulled by the two dogs, and onto the trail that led to the top of the cutbank on the edge of the river. At some point the bodies were dragged down the cutbank and dumped into the hole in the river. Clayson’s bicycle may have also been put into the water, as it was never seen again.

The articles of clothing removed from the bodies were taken back to the tent that O’Brien and Graves were staying in and most of it was burned, some in the stove and some in an outside fire. Left behind at the murder site were a number of items that had been removed or fallen from the bodies, as well as blood and some human body fragments that indicated what took place there. All this was later uncovered in a painstaking investigation and would serve as evidence in the trial of George O’Brien.

For anyone interested in more details, Malcolm’s Murder in the Yukon book gives a fairly vivid description of the murder event as deduced from the evidence later gathered at the site.

O’Brien’s Trip South

The next recorded sighting of O’Brien was on December 27, when travellers Jennie Prather and her husband bumped into him near the northern junction of the river trail and Pork Trail. He said he was heading for Atlin, so the Prathers invited him to join them on their southward journey. He did so, and after about a mile they all passed by within 65 feet of Clayson’s pool of blood in the bush. O’Brien made no mention of a partner, and what became of Thomas Graves remains a mystery.

For the next couple of days, O’Brien travelled off and on with the Prathers and stayed at the same roadhouses. He didn’t seem to be in a hurry, and while he wasn’t overly social, he didn’t avoid other people. At Schock’s roadhouse on Lake Laberge, he purchased a pair of black horses and sleigh. His reason for doing this is not known, but it resulted in bringing him into contact with the NWMP at Tagish.

On January 3rd or 4th of the new century, O’Brien turned up at Tagish with two black horses pulling a sleigh. Two dogs, including a big yellow one, were also with him. O’Brien had come almost 500 miles from Dawson and was now within striking distance of the American border and Skagway. What his plans would have been from there can only be a matter of speculation.