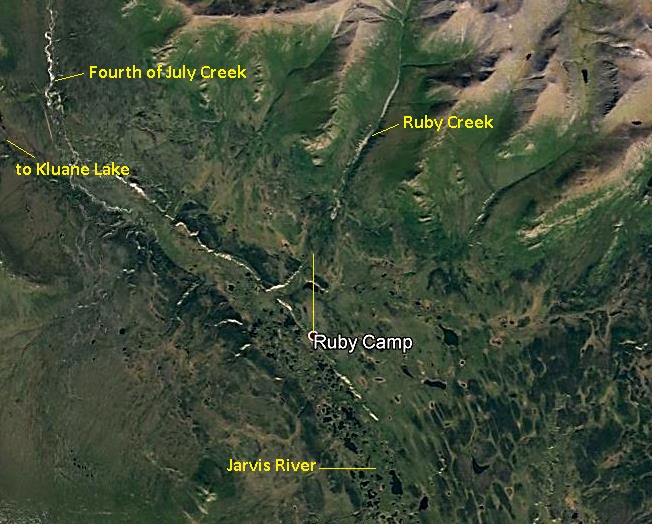

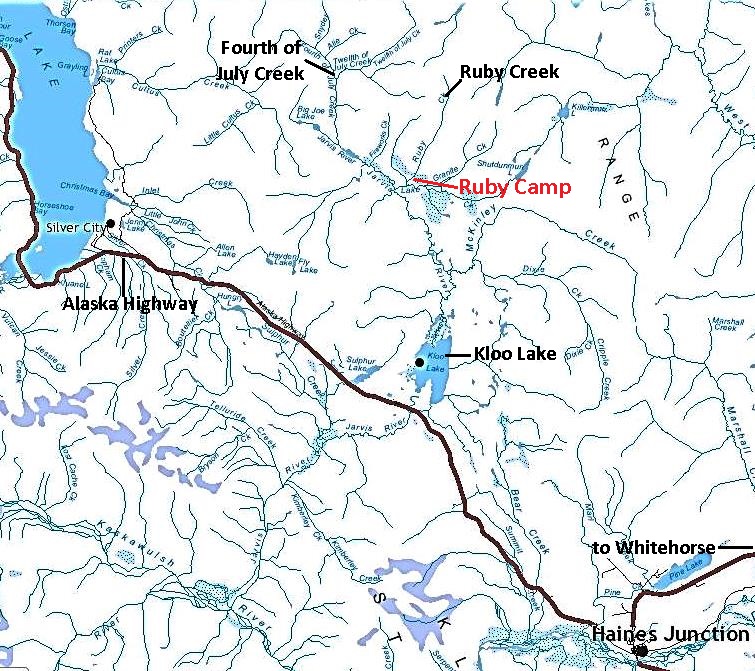

If you use Google Earth and happen to hone in on an area about 45 kilometers northwest of Haines Junction, a label pops up saying ‘Ruby Camp’. The label is actually about two kilometers south of where it should be, but even in its correct location you see nothing there. It is just a spot in the bush about 14 kilometers north-northwest of Kloo Lake, beside a small tributary of the Jarvis River called Ruby Creek. Ruby Camp’s appearance on Google Earth is purely historical, a short-lived base for several hundred prospectors and miners during a small gold rush into the Kluane region that began in the summer of 1903.

There is very little information on Ruby Camp, likely due to its short life and because newspapers were quick to report on new gold discoveries, but lost interest when the excitement faded. Ruby Camp does not show up in any internet, online newspaper, or archival searches that I have done. I have found only one photograph of Ruby Camp (and it is labelled as ‘Ruby City’) and one small sketch map that was part of a Northwest Mounted Police (NWMP) land reserve (and it did not refer to the location as Ruby Camp).

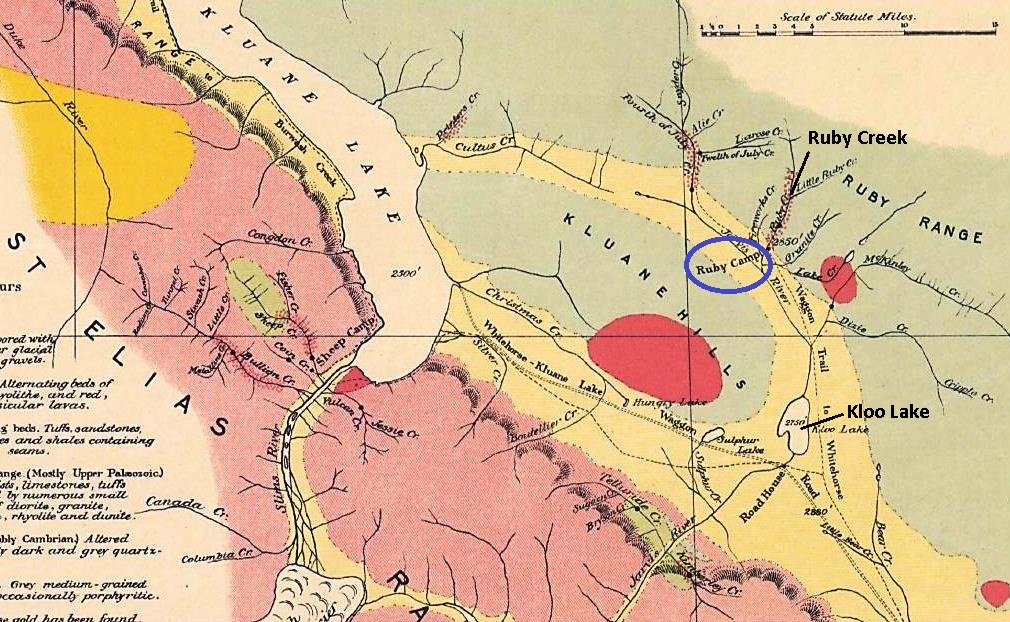

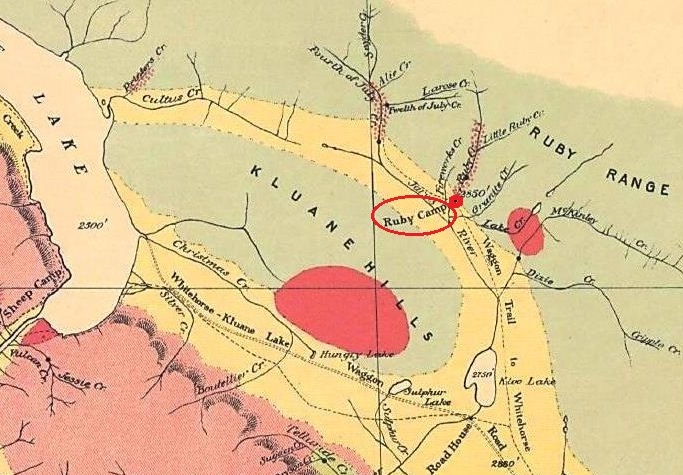

The only published map I have seen with Ruby Camp marked on it is one that accompanies a 1904 report of the Kluane Mining District by Geological Survey of Canada geologist R.G. McConnell. On a similar map he co-published in 1917, Ruby Camp does not appear. It seems a wonder, considering its relative obscurity, that Ruby Camp even came to be identified on Google Earth.

(from Geological Survey of Canada: Sketch map of Kluane Mining District, Yukon Territory, #894, R.G. McConnell, 1904)

The Kluane Gold Rush – 1903

At the time of the gold rush into the Kloo Lake area in July 1903, there had been little non-First Nation presence west of Whitehorse and virtually none west of Champagne. Only a handful of outside people had passed through in exploratory endeavors, starting with the expeditions of Edward Glave and Jack Dalton in 1890 and 1891. A few years later, Dalton began using the First Nation trail from the Haines, Alaska area north through Champagne and on to the Fort Selkirk area as a route to the Klondike for commercial enterprises.

In 1902 Harlan ‘Shorty’ Chambers, presumably seeing potential opportunities in the area, established a trading post and roadhouse along this trail at Champagne. Also in 1902, the Overland Trail from Whitehorse to Dawson was constructed, heading northwest from Whitehorse for 50 kilometers before turning north up the Little River valley near its mouth at the Takhini River.

The discovery of gold in creeks north of Kloo Lake was the event that first brought increased development, population and access into the region west of Champagne. It led to the establishment of a community at Silver City, roadhouse/trading posts at Bear Creek and Burwash Landing, other roadhouses that became focal points of activities, and the Kluane Wagon Road.

The original discoverers of gold in the creeks north of Kloo Lake were the First Nations people of that area, who reported it in the spring of 1903. On June 25, Dawson Charlie and Skookum Jim, two of the co-discoverers of the Klondike gold in 1896, along with six other people headed west from Whitehorse with a large amount of supplies. They were supposedly going on a hunting trip, but it resulted in Dawson Charlie staking a discovery claim on Fourth of July Creek, which he named for the date of discovery.

Two days later, on July 6, Bill Wiesdepp staked a discovery claim on nearby Ruby Creek. Wiesdepp, who operated a horse freighting business, had caught wind of the gold strike and with his partner Jack McMillan followed Dawson Charlie and company’s trail out to the Kloo Lake area. Why the creek was named Ruby is not known, but it may be because garnets, which resemble rubies, sometimes show up in a gold pan there.

(Yukon Lands Viewer)

The discoveries in Ruby and Fourth of July Creeks, along with others in the area, are in the Alsek River drainage, so the gold discoveries were referred to as the ‘Alsek diggings’ at the time. Subsequent discoveries later in 1903 and in 1904 in the Kluane Lake area to the west are located within the Yukon River drainage.

On July 10, when Dawson Charlie returned to Whitehorse to record his claim, his news of the new goldfield opened the floodgates. Three days after the news of the discovery broke, the Whitehorse Mining Recorder, R.C. Miller, wrote to the Department of the Interior in Ottawa that “the matter has created quite a furor here and I fancy fully 150 men have stampeded from here within the past two days”. This was a significant rush in a short time from a town of less than 1,000 people.

Men left Whitehorse on foot, some using horses or dogs for packing or pulling, and on July 14 the British Yukon Navigation Company (White Pass) steamer Clossett took 50 men and supplies up the Takhini River to the mouth of the Mendenhall River, at what was to become known as Mendenhall Landing. This 110-kilometer boat trip from Whitehorse eliminated travel on the first 80 kilometers of the trail into the Kluane region.

The first trails taken from Whitehorse to reach the Kloo Lake area would have been First Nation people’s walking trails. There is information about three different trails being used at first, but it is apparent that a foot trail heading west from the Overland Trail at the Little River quickly became the favored one, particularly since it also linked up with the steamer service to Mendenhall Landing. The general route of this trail was taken in construction of the Kluane Wagon Road the following year and the Alaska Highway 39 years later.

The trail into the Ruby Creek country has been, for many decades, on the west side of Kloo Lake, but the 1904 map by geologist R.G. McConnell and newspaper articles make it clear that the first trail used to access this area was on the east side of the lake. This is undoubtedly the same one taken by Glave and Dalton in their 1891 expedition. This trail continued beyond a number of small lakes north of Kloo Lake, then bent toward the northwest to follow the north side of the Jarvis River valley and on to Kluane Lake.

(from Geological Survey of Canada: Sketch map of Kluane Mining District, Yukon Territory, #894, R.G. McConnell, 1904)

The trail from Whitehorse to Ruby Creek was about 240 kilometers long, including the Overland Trail portion, a four to five day journey by foot. The 20+ kilometer section of the trail up and over the Bear Creek summit to north of Kloo Lake was difficult due to swamps and willow growth. However, over the summer of 1903, this First Nation walking trail was gradually transformed to a well-defined horse-packing trail from the amount of traffic over it. A year later there would be a much larger trail in place.

In addition to the first stampeders from the Whitehorse area, others started coming in, from both south and north over the route then known as Dalton’s Trail to Champagne, as well as from Dawson, Atlin and Skagway. News of the new gold rush was in the ‘outside’ newspapers by July 21, and people in places such as Seattle started organizing to head north, although most not coming until the following spring. By late July there were an estimated 300 men in the Kloo Lake area, and almost all of Ruby and Fourth of July Creeks, along with their tributaries, were staked up.

On August 4, R.C. Miller, the Mining Recorder, reported to the Department of the Interior in Ottawa that “the stampede to the new placer diggings west of Whitehorse continues with unabated vigor. It is within the mark to say that between 400 and 500 men have already gone in”. By early August, the steamer Clossett was making three trips per week between Whitehorse and Mendenhall Landing.

(Yukon Archives, E.J. Hamacher fonds (Hougen collection)), 2002/118, #394 – photo has been cropped)

Very little actual mining development work was done in the 1903 season due to a number of factors: the relative lateness of the gold discovery; the miners’ lack of knowledge of the country; the relatively basic trail access over a long distance; and the requirement to return to Whitehorse to register mining claims and obtain more provisions.

Miners spent the remainder of their time in 1903 locating, staking and recording their claims, assessing the claims by panning, building cabins and perhaps whipsawing timber to make lumber for sluiceboxes and other needs. As the winter closed in on the Kluane region, some miners remained on the creeks and turned their attention to acquiring provisions and equipment for winter development work on their claims, including digging shafts to try to locate bedrock.

The Northwest Mounted Police (NWMP) Presence

The NWMP established a presence in the Kluane region on the heels of the miners and prospectors flocking there in July 1903. The first tasks they attended to included putting up directional signs on the trails and establishing an enforcement presence to counter activities such as cache robbing that was taking place. One person wrote in a letter home that the NWMP were also “out in the hills picking up men … lost in the mountains, some crazy, some nutty, some starving, others played out”.

On July 31, NWMP Superintendent A.E. Snyder, based in Whitehorse, wrote that he was establishing a permanent patrol into the Kluane region goldfields from a base camp at Mendenhall Landing. The patrol would consist of three men, two of whom would be continually out on the trail. A senior officer from Whitehorse would also conduct frequent inspections into the area. Snyder said that he did not plan to establish a detachment in the goldfields until further developments in the area warranted it.

On August 3, Inspector J.C. Richards, after visiting the Kloo Lake area, recommended four sites for NWMP posts that he had marked out, one of which he called ‘Fields’, located on the north side of the Jarvis River midway between Ruby and Fourth of July Creeks. By December the NWMP had changed their preference to a site on Ruby Creek at the crossing of the trail to Fourth of July Creek and Kluane Lake.

In May 1904, the NWMP followed this up with an application for a 40-acre land reserve on the west side of Ruby Creek at this trail crossing. A wooden framed building 12’ x 20’ in size with canvas sides and a board roof was built on the site, a temporary structure that could easily be dismantled and removed if the amount of mining activity did not justify a more permanent structure. A sergeant and two constables were stationed at this post for the summer of 1904, but were withdrawn by the time winter set in.

Establishing Ruby Camp

One newspaper article indicates that by at least early August of 1903, a location for a potential townsite 2½ kilometers from the mouth of Ruby Creek was being considered if the gold discoveries turned out to be significant. While this scale of development didn’t happen, the site where the trail to Fourth of July Creek and Kluane Lake crossed Ruby Creek began to grow with tents and cabins. Known as Ruby Camp, it was located on the east side of Ruby Creek, across from the NWMP reserve, on a flat, open bench with a good supply of nearby timber.

Robert C. Coutts’s book Yukon Places and Names does not contain an entry for Ruby Camp, but for Ruby Creek it says that “during this period a small settlement of the same name grew up at the mouth of the stream, with a post office, roadhouse and stores”. There can be no doubt Coutts was referring to Ruby Camp, although the site was a couple of kilometers from his description of it at the mouth of Ruby Creek. The source(s) of his information is not provided.

(Gord Allison photo)

(Gord Allison photo)

In February 1904 a liquor licence was issued to Joseph Knapp for an establishment at Ruby Creek. Whether it had already been built or started or was only proposed is not known. A liquor licence cost $300, a hefty sum at that time, and included stringent requirements for the type, number, and standard of rooms. It would seem that a person acquiring a liquor licence would have been fairly serious about building, but it is not known if Knapp followed through on his plans.

The situation was better documented for another man, Jack McLean, who had been a ‘mixologist’ (fancy bartender) in Whitehorse. In early March 1904, freight was being hauled for him to Ruby Creek for his venture. In May when the NWMP submitted their application for a land reserve on Ruby Creek, it included a sketch map that showed McLean had established a roadhouse across the creek from the NWMP at the junction of the trails to Kluane Lake and Ruby Creek.

(from Yukon Archives GOV 1949, File 266)

In late April, McLean sent a letter from ‘Ruby’ to the editor of the Whitehorse Daily Evening Star with an update of activities in the area. He signed it off with ‘29 below, Ruby’, perhaps the claim number that his roadhouse was situated on, meaning the 29th claim downstream from Billy Wiesdepp’s discovery claim. An interesting newspaper note is that a man named J.E. ‘Eddie’ Marcotte, who had claims in the area, provided barber services at McLean’s roadhouse on Sundays.

(Yukon Archives, E.J. Hamacher fonds (Hougen collection)), 2002/118, #145)

(Gord Allison photo)

I have seen no reference to a store at Ruby Camp, as described by Coutts, although they were sometimes associated with roadhouses. As for his reference to a post office, the Canada Postal Guide for 1905 contains a record of closure for a post office at Ruby Creek, confirming that there was one at the site. In 1904, the NWMP delivered mail to Ruby Creek under an arrangement with the postal service. They would have had to deliver it to a place where the mail could be sorted and distributed, so perhaps the roadhouse served as the post office.

The 1904 Season

The 1903 season had not allowed the Kloo Lake area miners time to sufficiently test and assess their claims before the season ended. One knowledgeable prospector said that, “no prospecting that can place the value of the country beyond guesswork has as yet been done”. Going into the 1904 season, there were expressions of optimism, but some sources suggested that expectations should be tempered. A correspondent who had visited the goldfields came out with “an urgent appeal not to boom it, because nothing big is expected…”.

NWMP Assistant Commissioner Zachary Wood visited the region in April and went even further: “I do not wish to create a stampede, in fact I do not think it advisable for anyone to go in there at the present time…. Next fall would be the best time, as then the value and extent of the diggings will have been more fully determined and people will know just what they may expect”.

It is not known what effect these cautionary recommendations may have had, but that spring the claimholders who had not stayed on the creeks during the winter, as well as new people looking for an opportunity, began to pour into the region while travelling was still good on the frozen ground. 1904 would be the year to make or break the area as a good gold producer.

Considerable work appears to have been done over the winter and into the spring of 1904 on the trails to the Kloo Lake area, some of it funded by merchants of Whitehorse. Along with the increasing mining preparation activity and the trail improvements came the establishment of at least eight roadhouses between the Overland Trail and Kloo Lake, in addition to the existing one at Champagne. These provided services to travellers and took the pressure off of the miners to have to haul as much food with them along the trail.

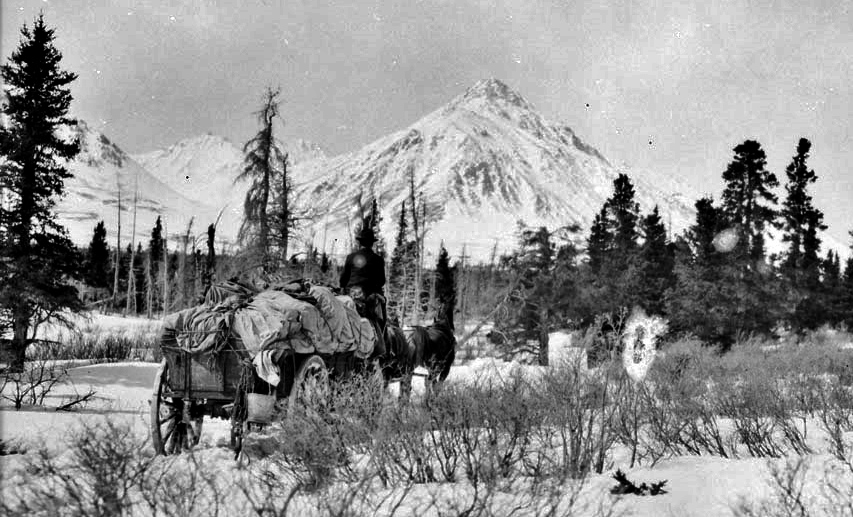

Also by this time, a number of small companies had begun providing both passenger and freight services by horse and sleigh or wagon from Whitehorse to the Kloo Lake area. These trips generally took about seven days and used the roadhouses that had been established along the route.

(Whitehorse Daily Evening Star, 25 March 1904)

Four-horse teams could be driven to the Bear Creek area, where Eli Proulx was building a roadhouse and White Pass & Yukon Route was building a warehouse (see link at end of article to story of Bear Creek Roadhouse). From there, single-horse sleighs were used to go over the summit and to the north of Kloo Lake. From that area, trails branched to the various creeks and dog teams were used to haul the freight there.

By early April, there were a reported 100 tents set up at Kloo Lake used by men relaying their supplies across the Bear Creek summit. On Ruby Creek, particularly the upper part where a lack of timber hindered the building of cabins, there were reported to be about 30 tents, each being occupied by an average of three men.

(Library & Archives Canada, #3401966)

NWMP Assistant Commissioner Zachary Wood noted in April that there were 800 to 900 men spread out over the various creeks. When he was at Ruby Creek, Skookum Jim was installing a boiler on his claim, the first such machinery to be brought in to the area. On Wood’s way back out to Whitehorse, he met 15 horse teams and 11 dog teams pulling sleighs with provisions.

Two other gold discoveries had an effect on how the miners of the Kloo Lake area were carrying out their activities. A significant gold discovery that had been made in the late fall of 1903 on Bullion Creek, near the south end of Kluane Lake, and another discovery in late May 1904 on Burwash Creek, to the northwest of Kluane Lake, both attracted miners who were already operating on Ruby Creek and other creeks in the Kloo Lake area.

NWMP Superintendent Snyder, who had accompanied Commissioner Wood on his trip, expressed his observation that the presence of gold in most of the creeks of the area meant that the continual discoveries being made caused many miners to move from creek to creek. Few miners stayed on any one creek long enough to prove the value of their claims, therefore limiting development work being done on any of the creeks.

Weather also worked against the Ruby Creek miners for the first part of the 1904 season. The early part of the summer remained quite cold, and snow and ice stayed in the creek bed into June, making it difficult to move dirt and keep water pipes from freezing. Then as summer emerged and the snow in the mountains melted, high water became a problem, and with no ability to deal with it, little mining was able to be done. Skookum Jim returned to his home in Carcross in mid-June because of the amount of water and did not plan to return until July.

A somewhat contrasting report came from two mining inspectors, Lachlin Burwash and Percy Reid, who made an inspection trip In June to the Kloo Lake and Kluane Lake gold creeks. They found about 200 men working in the Kloo area creeks, including 70 on Ruby Creek. They noted that considerable work had been done on Ruby Creek, with a number of deep shafts sunk, one of them to 60 feet.

(Brad MacKinnon photo)

In August the Ruby Creek miners had a rare short break from their hard work when they were visited by the Reverend Isaac Stringer (“the Bishop who ate his boots”, five years later). On August 7 he conducted a service for 28 men in a tent on the creek.

In the fall and early winter of 1904, the access picture in the Kluane region underwent a big change with the building of the Kluane Wagon Road. Starting from the Overland Trail about 50 kilometers northwest of Whitehorse, it went for 196 kilometers to Silver City on Kluane Lake, amounting to a total distance from Whitehorse of 246 kilometers.

The Kluane Wagon Road project included an eight-kilometer winter branch road north toward Ruby Creek, starting from near the south end of Kloo Lake. It may have been that this new road was put in on the west side of Kloo Lake, changing travel from the east side where the earlier trail was located, but this has yet to be confirmed.

By the end of the 1904 mining season about $20,000 worth of gold was taken from the creeks of the Kluane region, nearly all of it from Ruby, Bullion and Burwash Creeks. It was becoming evident that the Kluane gold creeks were not going to be another Klondike.

After the Gold Rush

The geologist R.G. McConnell considered the 1904 season to be a disappointing one, but retained a little optimism because the mining development was still fairly new and untested. However, he returned to the area in 1905 and found Ruby Creek almost deserted, the miners having moved on to Fourth of July Creek. That year less than $1,000 worth of gold was taken from Ruby Creek.

The NWMP withdrew their temporary post at Ruby Camp in the fall of 1904 after operating it for only the one season. Ruby Camp’s function as a central place for the Kloo Lake mining area likely ceased as quickly as it was established in the summer of 1903. Most or all of the tents that miners and others had set up there were probably removed by 1905, and the cabins that were built on the site perhaps persisted for a few years before being moved or cut up for firewood.

Ruby Creek was worked off and on for a number of years following the gold rush by a handful of people who retained a connection to the area. One was Joseph Knapp, who was issued the liquor licence at Ruby Camp in early 1904. He engaged in a few endeavors in the Kluane region, including a couple of stints prospecting/mining on Ruby Creek, in the winter of 1928/29 and again in 1938. In the fall of 1928, a newspaper noted with amusement that Knapp had shipped in a car to Whitehorse for transporting his mining equipment and provisions to as near as he could get to Ruby Creek.

Other than these types of ventures, Ruby creek seems to have been more or less abandoned until gold prices began to rise in the 1970s and the creek saw renewed mining interest, as did most gold creeks in the Yukon. In 1973 a new road was built from Kluane Lake to Fourth of July Creek, and about ten years later the road was extended to Ruby Creek, bypassing the Ruby Camp location by about two kilometers. This road enabled the introduction of machinery that could uncover the gold that had eluded the early miners.

For the past 30 years, Ruby Creek has seen more or less continuous mining activity, primarily by two long-time Haines Junction residents, Brad MacKinnon and Dale Brewster. MacKinnon, who was the first person to use modern machinery there to any extent, occasionally comes across old workings, noting that “it always amazes me to see the amount of work these old-time miners were able to accomplish by hand”.

Now at the Ruby Camp site where hundreds of prospectors and miners came and went and congregated, there is nothing visible until you look beneath the willows and find depressions in the ground of old building sites, various pieces of metal, and the inevitable piles of old rusty tin cans.

Updated May 11, 2020

Link to related article: Bear Creek Roadhouse

Link to related article: Kluane Wagon Road

Gord,

You do a fantastic job bringing life to a name on a map. Your thorough research with explanations and maps not only brings integrity but provides a far broader view of Yukon mining activity that is not just centered on major mining regions.

Ruby Camp gives us the view of what appears to be a self sustaining operation that has provided a living for an assorted number of people for a lifetime.

Thanks for your kind words, Lew. I value your input and the conversations we have, and some of the information you’ve provided me about the central Yukon should start showing up in stories here in the near future.