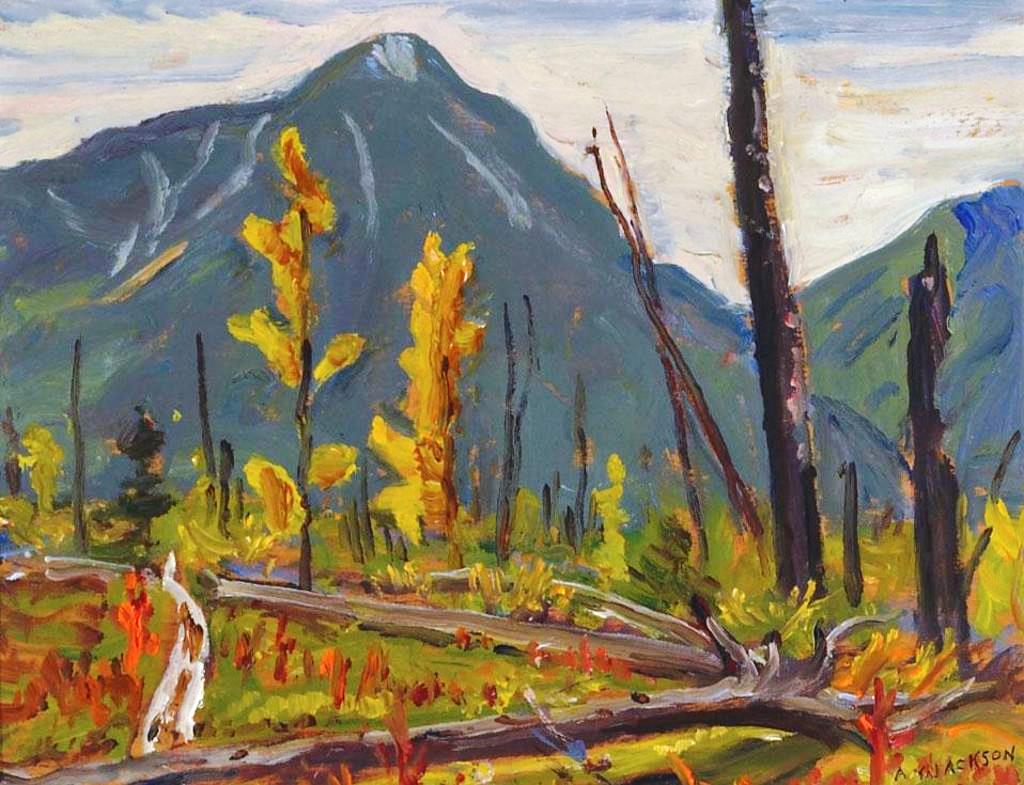

In October 1943, A.Y. Jackson, the well-known Canadian and Group of Seven artist, came to the Yukon to paint. He and another artist, Henry Glyde, were commissioned by the National Gallery of Canada to document in art the construction of the Alaska Highway as part of Canada’s war effort. Over a three-week period, they produced a number of oil and pencil sketches of the people, equipment and activities involved in the highway construction, as well as capturing some of the scenery of the Territory.

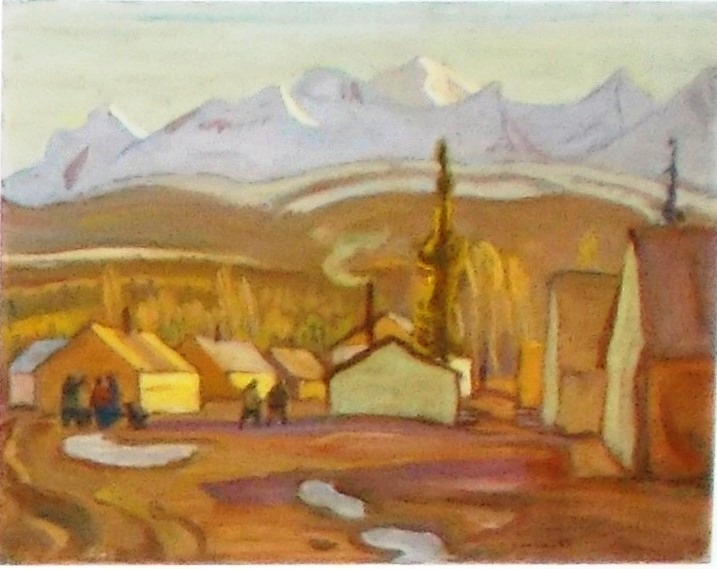

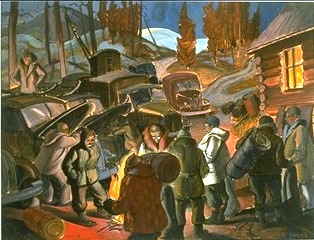

One of A.Y. Jackson’s paintings from this trip is called Camp Mile 108, West of Whitehorse. The mountain backdrop in this work of art would be easily recognized as that of Haines Junction by anyone familiar with the community. Henry Glyde also produced a painting called Alaska Highway Warming Up, Camp 108 Northwest of Whitehorse, Yukon which does not as accurately reflect the Haines Junction setting. These paintings of Camp 108, particularly A.Y. Jackson’s, are part of the first visual documentation of Haines Junction’s history.

(Gord Allison photo, 2020)

(Gord Allison photo, 2020)

(from the Canadian War Museum website)

A.Y. Jackson returned to Haines Junction on a trip back to the Yukon in 1964. He made a painting titled Haines Junction, Yukon that is in private hands.

The Pioneer Road and Alaska Highway

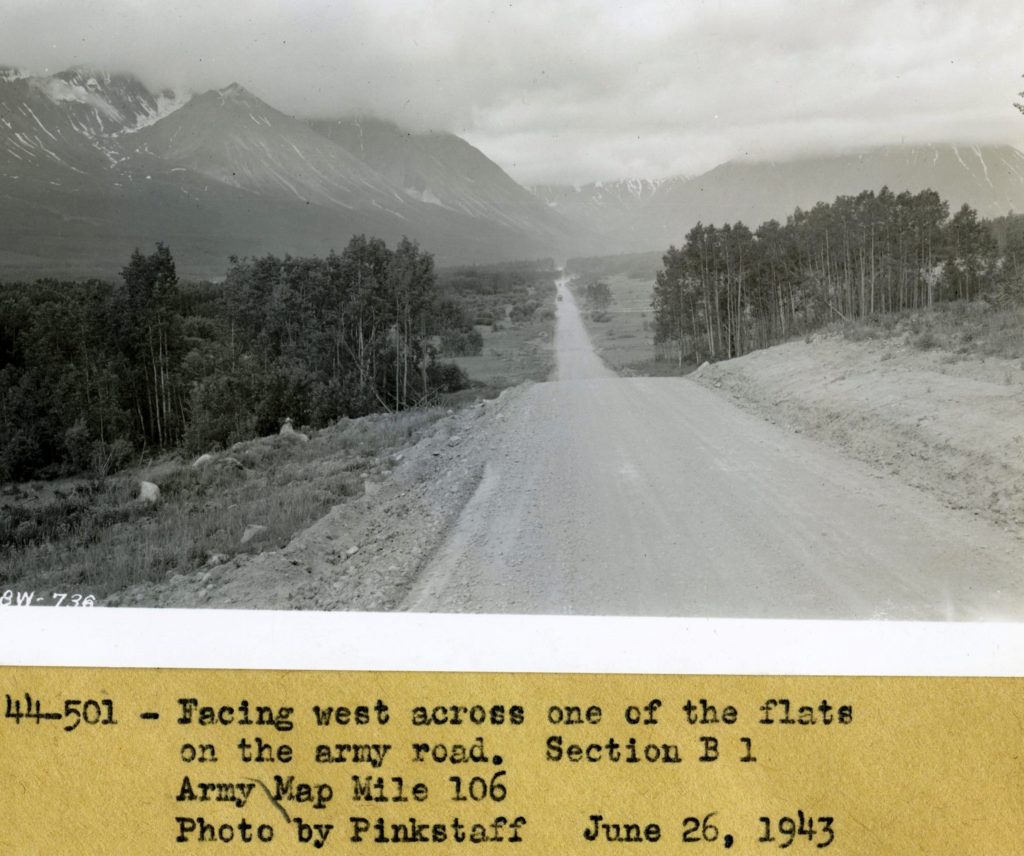

The Alaska Highway that A.Y. Jackson and Henry Glyde would have seen in the fall of 1943 was already a fairly different road than the original one that was pushed through the year before. The original road, usually termed the ‘pioneer road’ or ‘army road’, was built by the United States Army Corps of Engineers beginning in early March 1942 and was completed in less than nine months. It was rushed through for the purpose of getting military vehicles to Alaska to assist in the response to the Japanese aggression in the North Pacific.

The pioneer road was roughly 1,600 miles long from Dawson Creek, BC, through the Yukon to Delta Junction, Alaska. It was officially opened on November 20, 1942 in a ceremony at Soldiers Summit near the south end of Kluane Lake. However, much of the road was not passable by normal vehicles, being only of sufficient quality and width to enable travel by four- and six-wheel drive military vehicles.

As the pioneer road to Alaska was being built by the U.S. Army in 1942, the U.S. Public Roads Administration was following not far behind with civilian Canadian and American contractors to expand and upgrade the road for military as well as post-war development purposes. The highway was divided into six construction sections, each with a management contractor to oversee the other contractors, and each with its own mileage system. Section B went from Whitehorse (denoted as Mile 0) to the Yukon-Alaska border, a stretch of over 320 miles, with the Dowell Construction Company as the management contractor.

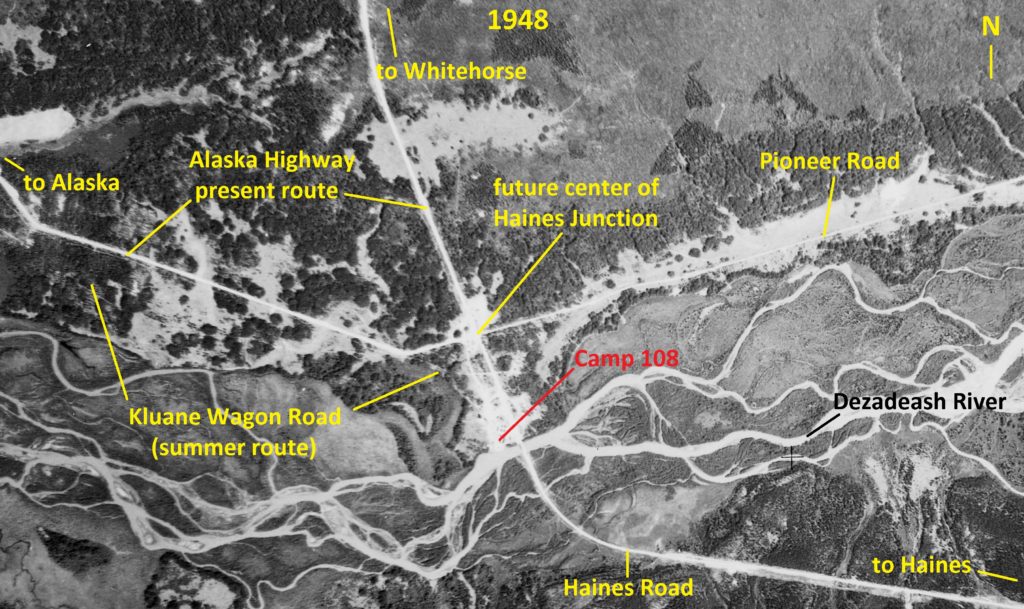

(National Archives & Records Administration, #44-0501)

Camp Mile 108

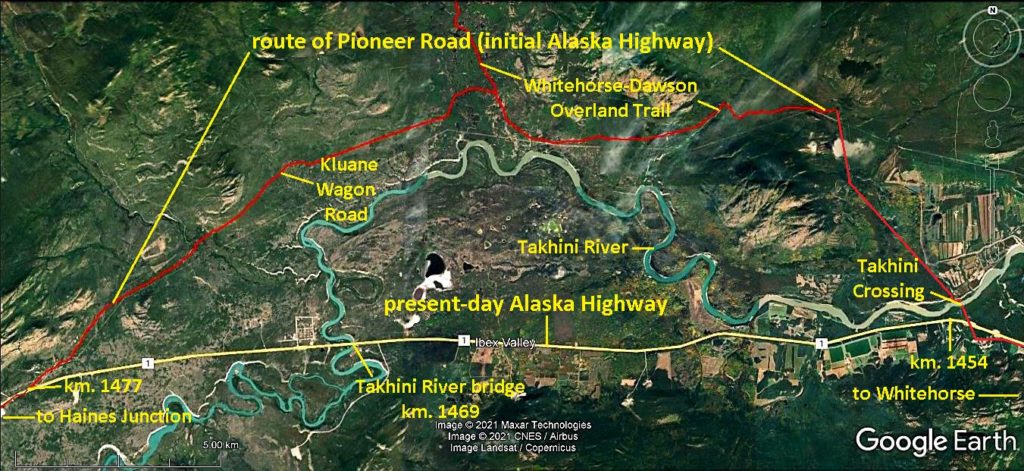

So why was the ‘Camp Mile 108’ of Jackson’s and Glyde’s paintings at the future site of Haines Junction called that? Until a bridge could be built where the Alaska Highway now crosses the Takhini River at km. 1469, the pioneer road took a longer route on the north side of the Takhini River valley using portions of the Whitehorse-Dawson Overland Trail and Kluane Wagon Road, which had been built in 1902 and 1904 respectively.

(Google Earth)

By this route, the distance from Whitehorse to the future site of Haines Junction on the Dezadeash River was 108 miles. Here a construction camp was established by a civilian contractor, Haas-Royce-Johnson, and given the name Camp Mile 108, or simply Camp 108. Other camp locations were similarly named for their mileages from Whitehorse, such as those at Mile 59 (Mendenhall River, also known as Jo-Jo) and Mile 88 (Canyon Creek).

Camp 108 was situated where the Dezadeash River would be bridged in late 1943 by a new military road from tidewater at Haines, Alaska, 159 road miles to the south. The Haines Highway, as it is now called, terminated where it met the Alaska Highway, leading to the location and the community that was soon to grow there being called Haines Junction.

The pioneer road in 1942 came to Camp 108, and the future site of Haines Junction, from the east. A revision of the highway in 1943 took the route farther to the north and then eventually swung around to approach the Camp 108 site from that direction. The story behind this is somewhat complicated and a separate one for another time.

(National Air Photo Library, A11539, #132)

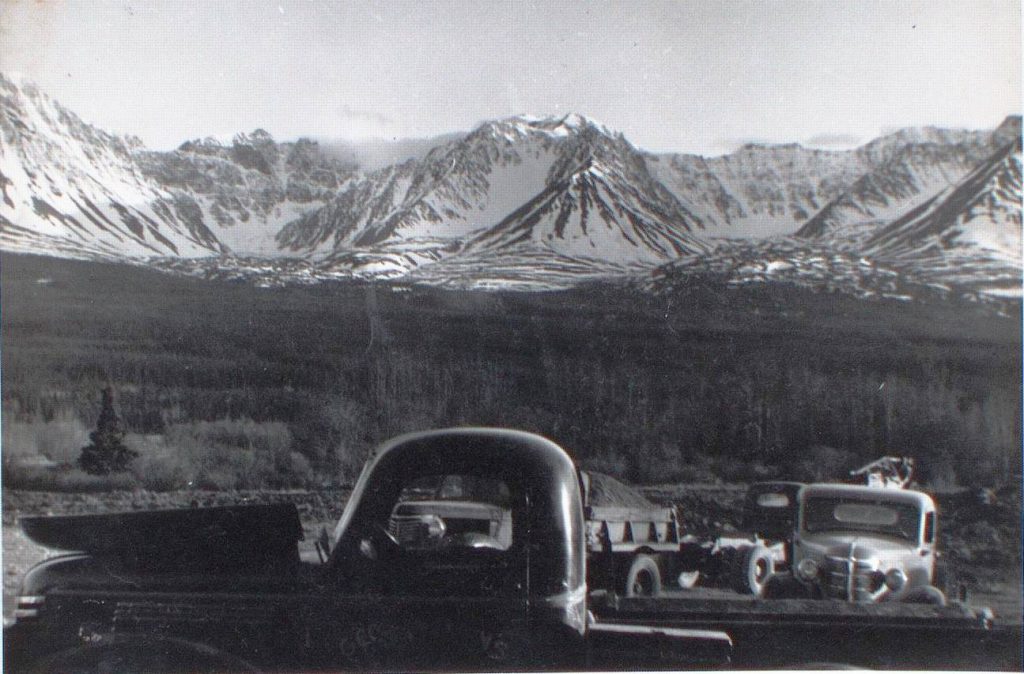

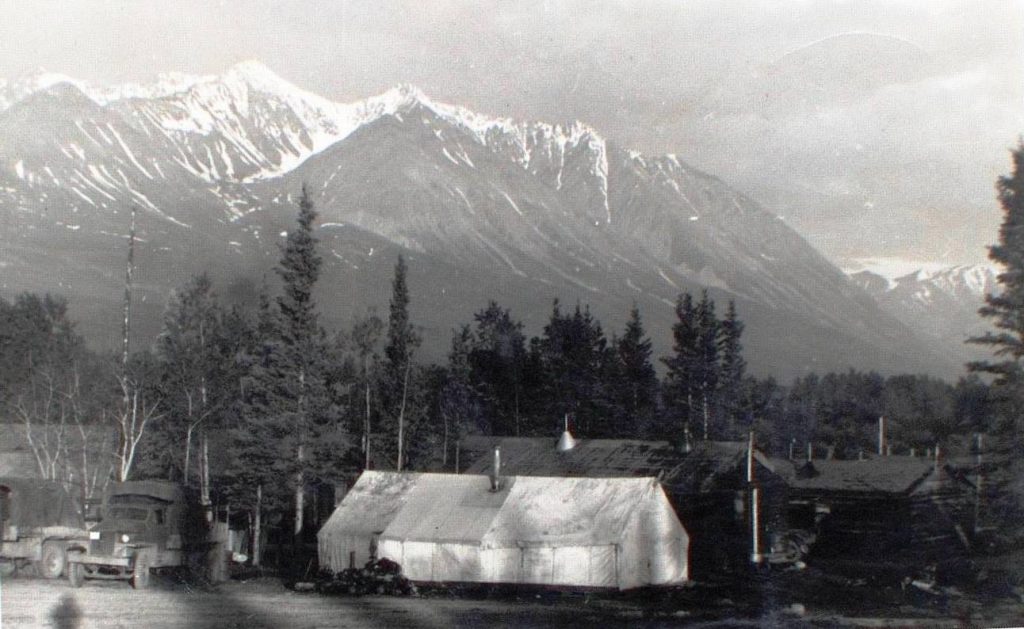

There seems to be few photographs of Camp 108, but there were two taken in the summer of 1943 by Glen Chapman, an American civilian laborer for the Dowell Construction Company. One picture appears to have been taken in early summer and the other later in the summer.

(Yukon Archives, Glen F. Chapman fonds, Acc. #2013/121, #152)

(Gord Allison photo)

(Yukon Archives, Glen F. Chapman fonds, Acc. #2013/121, #153 – image has been cropped)

(Gord Allison photo)

Where Camp 108 was established was not in an isolated region like many sections of the pioneer road were. It was in an area used by the Champagne & Aishihik First Nations people and known as Dakwäkäda, meaning ‘high cache place’. It was also at a crossroads of their east-west foot trails in the Dezadeash River valley with trails running to the north and south. Before the pioneer road came through, the routes of these trails had been generally followed by the Kluane Wagon Road, which ran from the Takhini River area to Silver City on Kluane Lake.

Small settlements existed at Champagne and Canyon Creek to the east of Camp 108 and at Bear Creek and Kloo Lake to the northwest. All except Canyon Creek had trading posts that provided some services to the workers on the pioneer road, but Dorothy Mackintosh’s lodge at Bear Creek was particularly favored by them. She had a store and rooms, in which she could house 15 people, but it was her garden produce and home cooking and baking that attracted road workers to her establishment (see link to Mackintosh Trading Post article at end).

The camp was still called Camp 108 when A.Y. Jackson and Henry Glyde visited there in October 1943, but the name was not to last much longer. The temporary section of pioneer road in the Takhini River area was abandoned by November when 15 miles of new road and a new bridge at the present river crossing were completed. This new route along with other revisions to the pioneer road shaved many miles from the 108 distance.

In July 1943, what had started out as the pioneer road in March 1942 was officially named the Alaska Highway, after being informally called a few other names, most notably the Alcan Highway. By the end of 1943, much of the rough and narrow pioneer road was transformed to an all-weather military highway.

A.Y. Jackson’s Life and 1943 Yukon Trip

Alexander Young Jackson was born in Montreal in 1882 and moved to Ontario in 1913, where he became an outdoors painter. He was already becoming known as an artist when he joined the First World War in 1915 with the Canadian Army’s 60th Battalion. He was wounded ‘going over the top’ at the Battle of Sanctuary Wood in Belgium on June 3, 1916. After recovering, he returned to the front and became an official war artist, painting scenes of war landscapes that are held at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa.

Jackson continued in this capacity after the war for the Canadian War Records Office until 1919. That year, he and six other prominent artists organized informally to create the Group of Seven, landscape painters who wanted to record the Canadian landscape and create a new and unique Canadian art identity. For the next couple of decades, Jackson continued to paint and teach painting in Ontario and Quebec until accepting a position in 1943 at the Banff School of Fine Arts in Alberta.

(F 1066, Archives of Ontario, I0010313 in Wikipedia)

By this time World War II was on and A.Y. Jackson was 60 years old, but he wanted to do his part in some kind of official capacity. The opportunity came in the fall of 1943 when it was arranged that he and another artist would “make studies of the Alaska Highway for the National Gallery of Canada”. The other artist was Henry G. Glyde, a fellow instructor at the Banff school who had become friends with Jackson and was invited on the trip.

The permissions and travel arrangements for the trip involved both the Canadian and American governments, taking considerable time and exchanges of correspondence. The artists were of a low priority with a war going on and permission was not granted until mid-October. Jackson and Glyde were given a ride on a transport plane from Edmonton to Whitehorse, landing there on October 14.

The two artists were mainly guests of the American military, who provided transportation for them and accommodation at the highway camps. They had to show their military permits at every camp they stopped at and were frequently challenged by soldiers to show their papers.

Jackson said that “we had heard stories [that this country] was just a great stretch of monotonous bush”. However, they seem to have been surprised by the breadth and beauty of the landscape and the activity they were witnessing, with Jackson stating that “we could have devoted months to sketching the construction work along the road or the endless vistas of country”.

Jackson and Glyde had fairly ambitious plans for painting, but as it turned out they only travelled and made their art along the Alaska Highway from Whitehorse to Kluane Lake. They did not have the time needed to make oil paintings of everything they wanted, as noted by Jackson: “in many places we got out of the car to make a 15-minute drawing and found enough paintable subjects to make us want to camp right on the spot for a week”. They resorted to making pencil sketches with coded abbreviations and numbers for colors and tones, and then later at their place of accommodation they finished their sketches in color.

Jackson and Glyde also painted scenes on the Haines Road, which was barely completed by October 1943, as was the bridge over the Dezadeash River beside Camp 108. They would have had to get a ride with a military vehicle to be able to carry this venture out.

Jackson summarized their Yukon experience with this: “perhaps it was the crisp October weather with the low sun, the somber richness of the colors, the frost and patches of snow, the ice along the edge of the rivers, but whatever the reason, we found it fascinating”. It seems he and Glyde may have been starting to fall under the Spell of the Yukon.

Jackson and Glyde painted prolifically and regarded their Alaska Highway trip as a success, but they also knew they had missed a lot and wanted to return. They applied for permission to return in the spring of 1944, but the response was not as welcoming as the previous year. They were offered to be flown to Whitehorse, but from there they would be on their own for transportation and accommodation. Jackson declined in his brusque way with “to hell with them” and stayed in Alberta to paint.

A.Y. Jackson returned to the Yukon in 1964, when he was 81 years old, and painted mainly in the Dawson and Mayo areas. However, he also made a trip to Haines Junction, where he produced a small (14.1″ x 10.4″) painting called Haines Junction, Yukon. This painting was last sold in 2008 for $20,700 and is in a private collection in Toronto.

(from Canadian Art Price Index website)

Jackson had so much more of the Yukon to explore on his second trip, but returning to Haines Junction perhaps hints that he had developed an affinity for the area. The year after his 1964 Yukon trip, he had a stroke that ended his painting career. A.Y. Jackson died in Toronto in 1974 at the age of 91.

From Camp 108 to Mile 1016 to Haines Junction

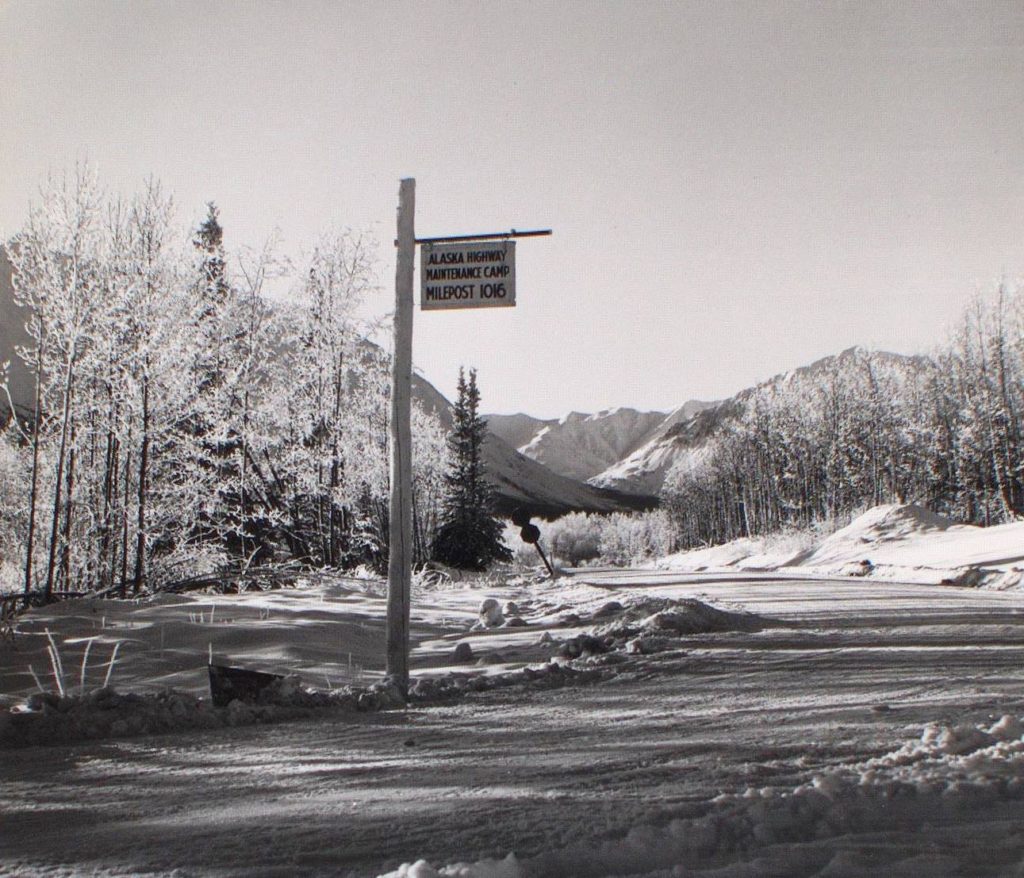

Upgrading and revisions to the Alaska Highway continued and at some point an accurate mileage measurement was made along it from Mile 0 at Dawson Creek, BC and ending at Mile 1422 at Delta Junction, Alaska. This new mileage system resulted in places along the highway becoming known by their milepost. The first use of a milepost designator in the Whitehorse Star newspaper was on December 8, 1944. It is likely that physical milepost markers were placed early on at prominent locations, and in 1947 mileposts were installed at every mile along the length of the highway.

Communities, highway maintenance camps, highway lodges, campgrounds, and river and creek crossings became known by their milepost numbers as commonly as by their names. This use of milepost descriptors continued into the 1970s until the introduction of the metric system in Canada made them obsolete.

The Camp 108 location was measured to be at Mile 1016, which appears to have quickly become the new name for the highway camp and the settlement that was beginning to develop around it. Mile 1016 first appeared in the Whitehorse Star on December 20, 1946 in a British Yukon Navigation (White Pass) bus advertisement that showed bus stops by their milepost locations rather than their names.

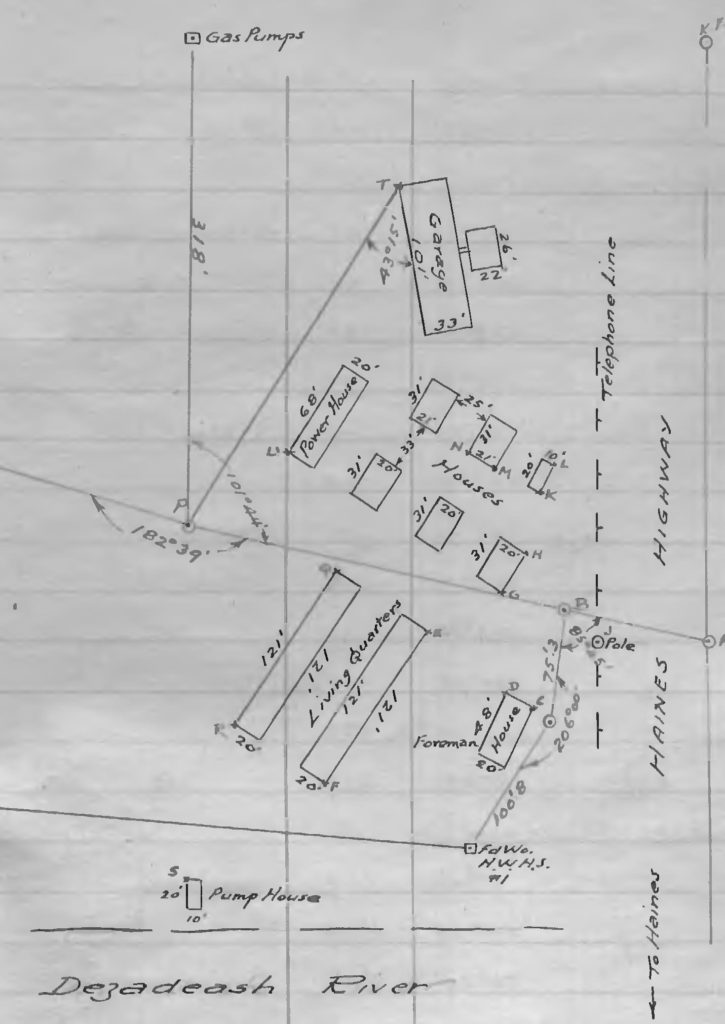

On April 1, 1946, the U.S. Army handed over the control, operation and maintenance of the Alaska Highway to the Canadian Army’s Northwest Highway System. By that time former Camp 108 was more permanent and became known as the ‘Army Camp’, as was the case in some other highway communities. In Haines Junction, this name for the highway maintenance area persisted for the next three decades, even following the camp to a new location across the Haines Road and after control of the Highway was turned over to the Department of Public Works on April 1, 1964.

(Canada Lands Survey Records, FB 23258)

When and by what official means, if any, the community of Haines Junction came to be given its name is not clear. Beginning in June 1946 there were a number of parcels of land staked in the vicinity of the junction of the Alaska Highway and Haines Road, and land applications submitted for some of them referred to the location as Haines Junction.

(Natural Resources Canada #1994-507)

By 1949, when a preliminary survey was made for a planned townsite, Haines Junction was a growing community with a store, tourist lodge, gas stations, highway maintenance camp, Royal Canadian Mounted Police detachment, a Forestry cabin, a scattering of dwellings, and the nearby Dominion Experimental Farm. In a 1949 voters list for the area, there are 42 names, which would not have included children and a number of First Nations people who had moved into the community but did not yet have the right to vote. There is no listing for Haines Junction in the 1951 census, but the 1956 census shows 74 names.

As highway improvements and revisions were carried out over the next seven decades up to the present, the mileage continued to shorten. The current mileage from Whitehorse to Haines Junction along the Alaska Highway is about 95 miles, three less than the post-war mileage to Mile 1016 and 13 less than the mileage to Camp 108 in 1943.

(Gord Allison photo)

After the metric system was brought into force in Canada, and following continued revisions to the Alaska Highway, the location of Haines Junction on the highway at present is Kilometer 1578. It is doubtful that many residents know this number, and even more doubtful that any care about it.

On the other hand, Mile 1016, or simply 1016, will long be associated with the town of Haines Junction. For a number of years a group of resident musicians played together under the name of the 1016 Band. The Mile 1016 Pub has been serving excellent food and good times for several years now. A local resident who has 1016 as his cell phone number can tell if someone he gives it to is a long-time Yukoner by their reaction to the number.

Camp 108, in contrast, was a short-lived name that has been mostly forgotten in Haines Junction’s history. It experienced a bit of a revival, though, beginning in the spring of 2017 when Roberta Allison brought A.Y. Jackson’s Camp Mile 108, West of Whitehorse painting to the attention of the Village of Haines Junction. Mayor Michael Riseborough and his Council took the interest and initiative to contact the National Gallery of Canada and obtain a print of the painting, as well as another of Jackson’s called The Highway Near Kluane Lake. On September 9, 2017, the prints were unveiled at the St. Elias Convention Center as part of an event celebrating the 75th anniversary of the Alaska Highway.

(Gord Allison photo)

There are likely not many communities in Canada that have their beginning recorded in a painting by a Group of Seven artist. Haines Junction’s membership in that unique club is undoubtedly due to the inspiration A.Y. Jackson found in the spectacular mountain setting at Camp 108.

A.Y. Jackson for instance

83 years old

halfway up a mountain

standing in a patch of snow

to paint a picture that says

“Look here

You’ve never seen this country

it’s not the way you thought it was

Look again”

– Al Purdy, “The Country of the Young”

Links to related stories: Kluane Wagon Road part 1, part 2, part 3 and Mackintosh Trading Post

Updated January 5, 2022

Nice to see the Jackson works

Gordon, in my aunt’s 1948 journal , she makes no reference to Haines Junction, which you noted in an email. Do you assume the name of “Hanes Junction” was not yet established?

Hi Tom. The name was certainly in use by then – I’ve seen it in land documents from 1946. I would guess that Mile 1016 was still being used as much or more by local people though. I know your family stayed at Mackintosh Lodge, 6 miles away, but Haines Junction was a developing town and it does seem odd that your aunt didn’t make any mention of it, by any name.

This is such an interesting write up and photos. I have often pondered the history of the highway and how it has changed over the years. I learned a lot reading this, including the interesting story of A.Y. Jackson visiting and painting in the area.

Thank you very much for the comment. I enjoyed doing this story.

Gord this is so excellent! Thanks for doing the work and sharing it with all of us!

Glad you enjoyed the story, Paula, and thanks very much for letting me know.

I’m always very pleased find one of your articles when I’m looking for links to expand on subjects on my website. Great work as always, Gord – I can always count on your research to be impeccable.

Thank you very much, Murray, that means a lot coming from you. And likewise – often when I’m looking for information I go to ExploreNorth and invariably find it there, and/or a link to something that is helpful.