In the 1960s when I went on occasional boat trips with the Bradley brothers of the Pelly River Ranch to Fort Selkirk, they would point out things of interest along the way. One was an old road that ran along the north edge of the Pelly River at the foot of a basalt cliff a couple of kilometers down from the ranch. Just after that was a short stretch of mildly swift and choppy water called ‘Schaeffer’s Riffles’ that they said was named for people who ran a roadhouse near there on the Overland Trail from Whitehorse to Dawson City. They explained that where the roadhouse used to be was now under water because of the river current cutting away the riverbank there.

These things the Bradleys talked about were difficult to understand at my young age, but they left enough of an impression to remain in my memory. Decades later I tried to learn more about the history of that place and endeavored to piece together its story. This article describes the historical and geographical setting for the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse, followed by information about the people who operated it and made it their home.

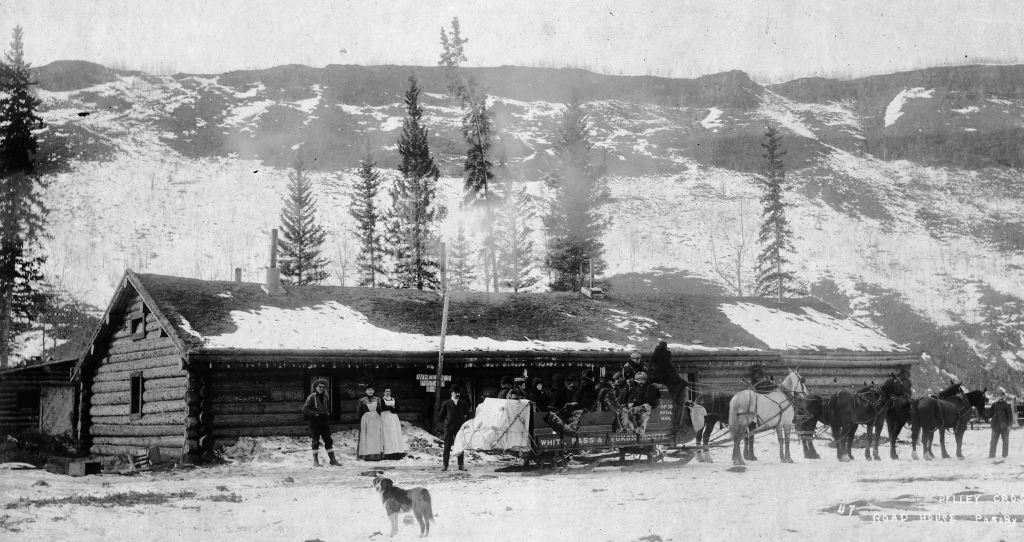

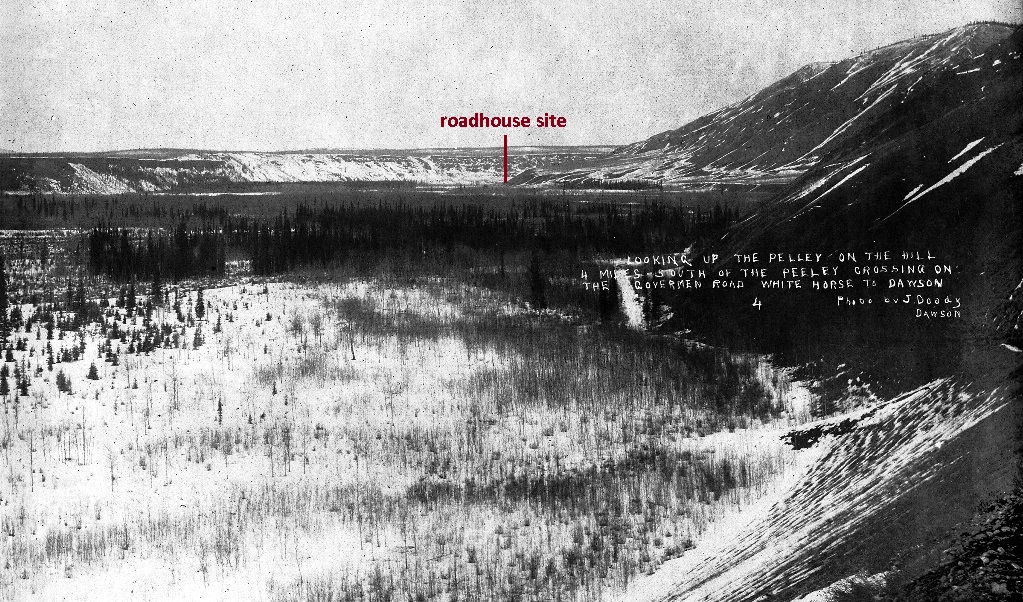

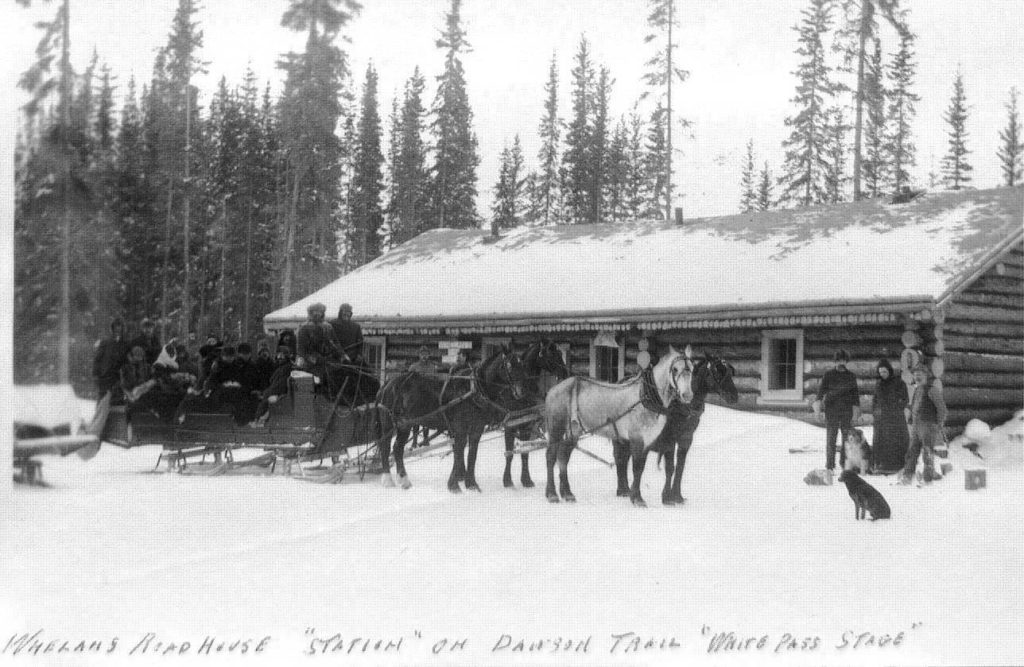

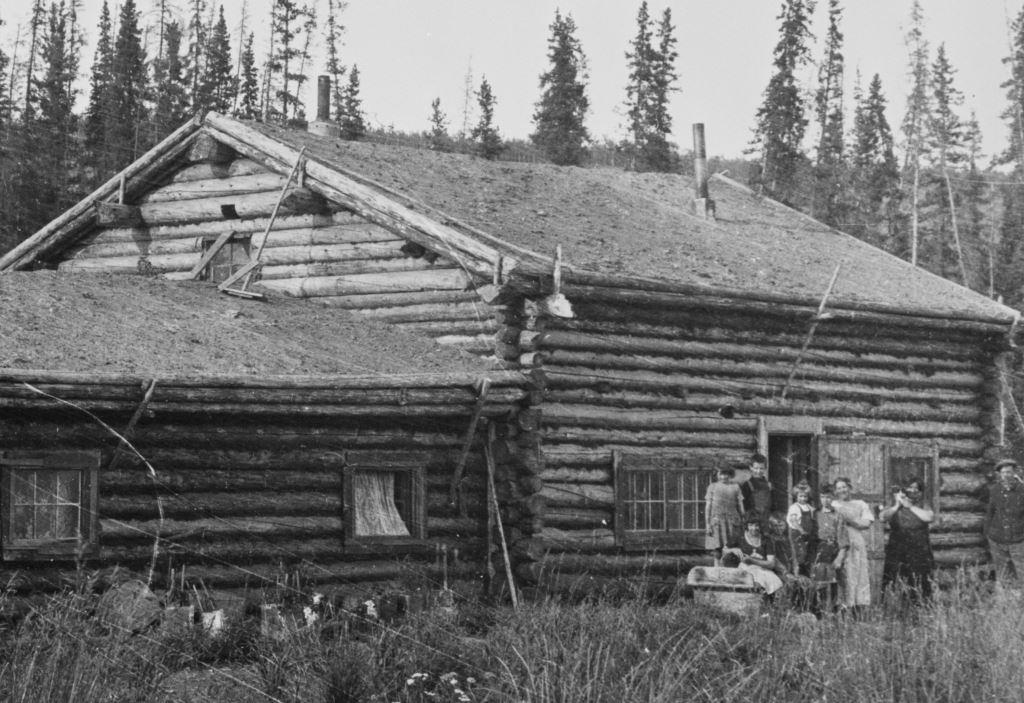

(Yukon Archives, Robert Coutts fonds, Acc. 86/15, #37 – photo has been cropped)

The Setting

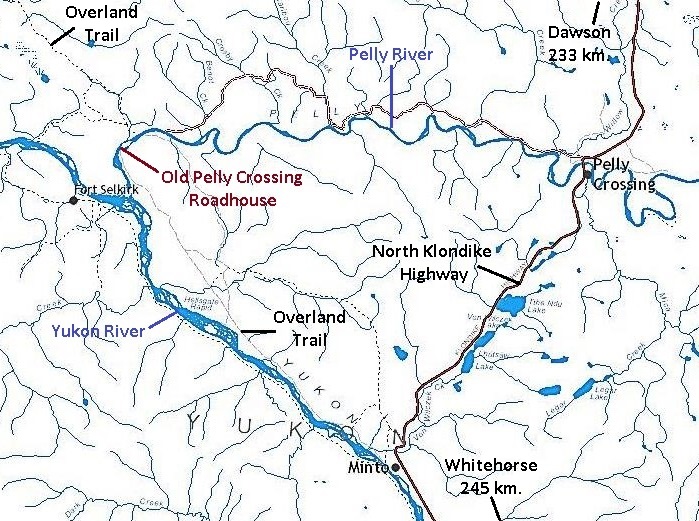

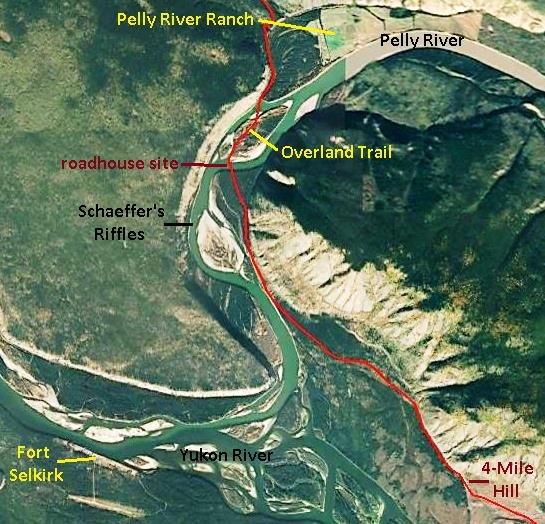

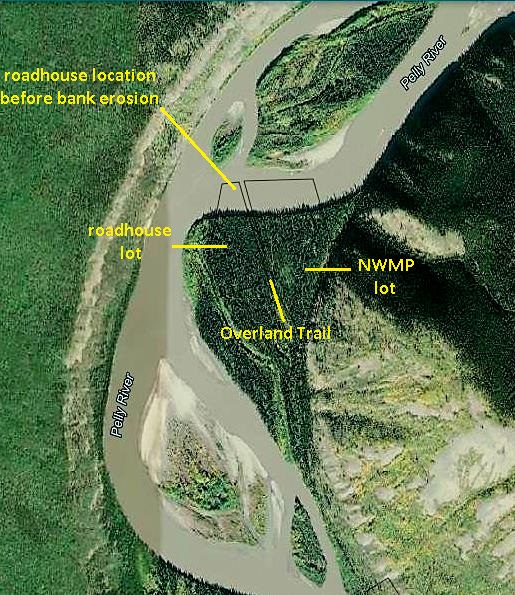

The Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse was located about 53 river kilometers down the Pelly River (west) from the present-day community of Pelly Crossing, and about seven river kilometers from Fort Selkirk. The site is where the Dawson-Whitehorse Overland Trail crossed the river during the years 1902 to about 1924 when that section of the Trail was in use. On the left limit (south bank) of the river was the large roadhouse, operated by a number of different people over those years, beginning with Thomas and Norah Whelan who established it and ending with Alexander and Margaret Shaver who ran it the longest.

(GeoYukon)

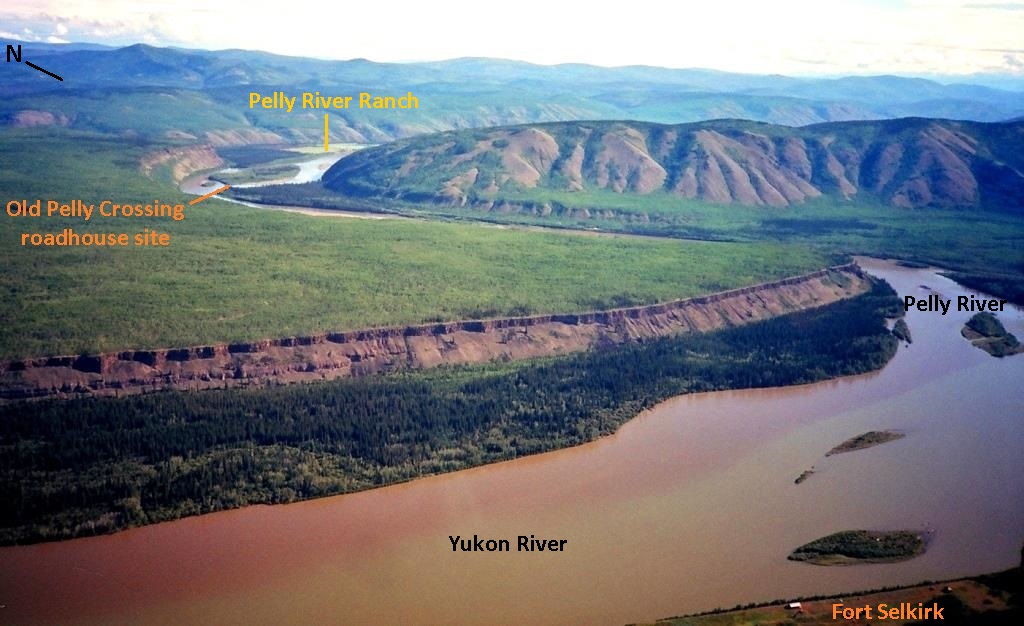

(Gord Allison photo)

The Overland Trail (1902)

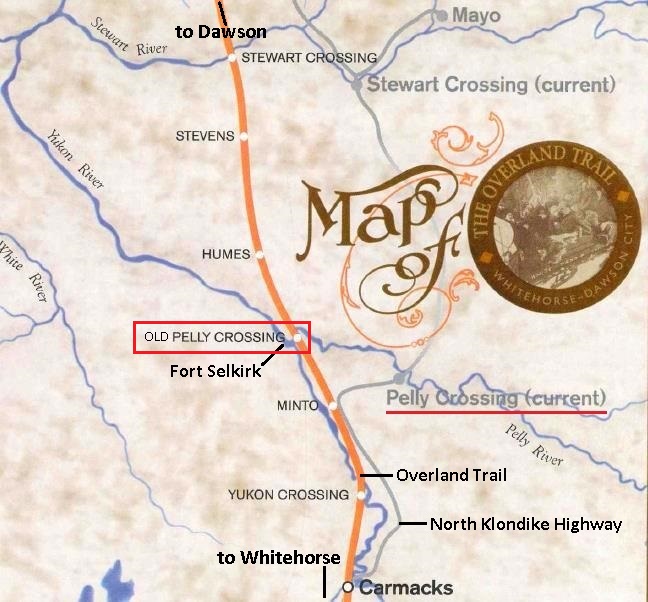

During the Klondike gold rush, winter travel between Whitehorse and Dawson was along the 450 miles (725 kilometers) of Yukon River ice. This river trail was travelled in both directions by people using various modes of human-, dog- and horse-powered transport. It was used from when the river froze solidly enough in late fall for travel until it became unsafe at spring break-up.

In May 1902, Yukon Commissioner James Ross secured federal funding for an overland trail between Dawson and Whitehorse to provide a safer and more reliable winter connection between the communities. That same month, Territorial Engineer William Thibaudeau set out from Dawson with a small crew to lay out the route for the road. The White Pass & Yukon Route was given the contract to build the road, and later in the summer work crews were sent out from Dawson and Whitehorse to carry out the construction.

The road construction was 530 kilometers of manual labor, with the assistance of horse-drawn equipment, to cut the road through the timber and brush, make sidehill cuts across hillsides, and bridge over streams and gullies. The work was completed in October and the road officially opened later that month.

The first traffic on the road left Dawson on October 28, 1902 with provisions for new roadhouses. The first mail stage left Whitehorse on November 2, but didn’t arrive in Dawson until November 12 due to ice issues at the Stewart River and some bare roads. Light wagons were used until the road had enough of a snow base that they could be replaced by sleighs.

More information about the Overland Trail can be found in previous articles at The Dawson-Whitehorse Overland Trail – Overview and The Overland Trail: Stewart River to Pelly River .

The Overland Trail Roadhouses

Right behind the Overland Trail construction came the building of roadhouses, horse stables, and associated infrastructure, and eventually North-West Mounted Police posts. Most of the roadhouses and stables were built in the late summer and fall of 1902 so that they were able to provide their services during that first winter the road was in operation.

(Yukon Government, Dept. of Tourism & Culture, “The Overland Trail: Whitehorse-Dawson City”, p. 14)

Hugh Bostock, a geologist with the Geological Survey of Canada who spent many years working and travelling in the central Yukon in the 1930s and ‘40s, described the function and importance of roadhouses: “here board and lodging as well as fresh teams of horses and drivers were provided for the travellers and the mail stages. The [roadhouses] contained all the necessities of life and the comforts of those days for winter travel and were a welcome and vital refuge for man and beast from the intense cold”.

There were over two dozen roadhouses that operated at various times during the life of the original route of the Overland Trail. Fourteen of them were White Pass & Yukon Route roadhouses and mail stops, and they were operated consistently and to a high standard. Other roadhouses were independently owned and operated, and most didn’t last for many seasons.

The White Pass roadhouses, of which Old Pelly Crossing was one, were on average 38 kilometers apart. They operated under a variety of arrangements, some being owned by White Pass with hired employees or leased out, and some privately owned with their services contracted to the company.

There was an additional arrangement that had White Pass’s steamboat captains engaged in operating roadhouses during the winter off-season. This was to encourage the captains to stay in the Yukon and reduce the risk of losing their expertise and knowledge of the river if they went ‘outside’ for the winter and did not return. What financial or other agreements may have been made to facilitate this arrangement is not known.

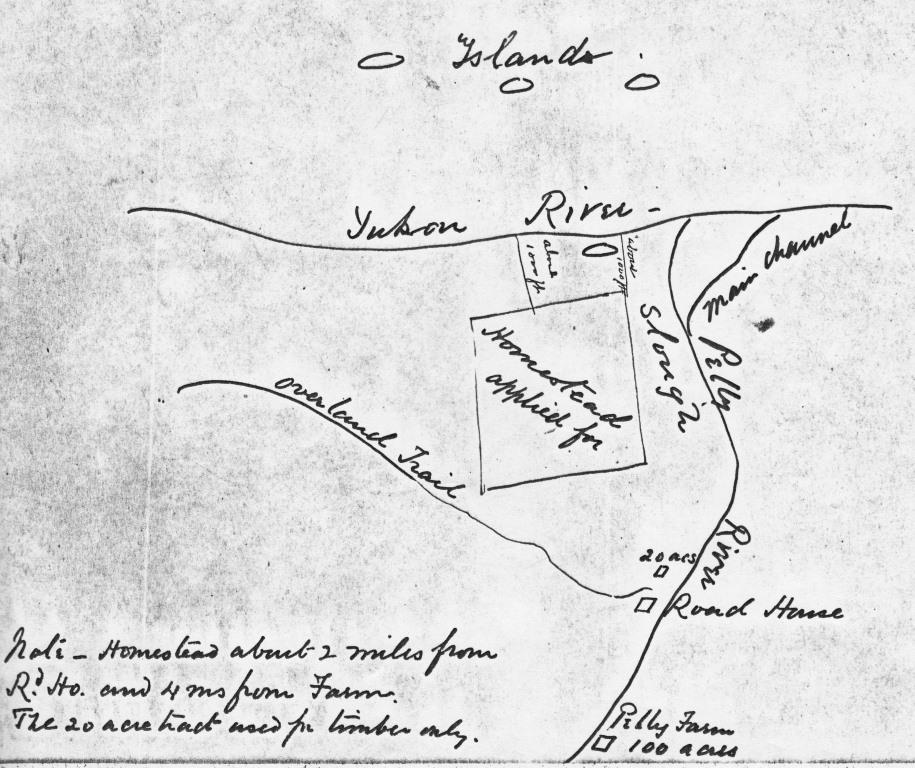

In at least two cases, the captains rather than White Pass came to own the land their roadhouses occupied, suggesting that they also owned the buildings, perhaps with the company subsidizing or assisting them in some way. One of these captains was Thomas Whelan, who applied in July 1902 for 20 acres of land for a roadhouse five kilometers up the Pelly River from its mouth at the Yukon River near Fort Selkirk.

Running a roadhouse in the winter was not easy work, especially during very cold weather with the low daylight hours. Firewood had to be cut and packed inside and water hauled from a hole cut in the river ice or, if lucky, a well. Inside the roadhouse there was food and bed preparation, keeping fires and lanterns going, doing dishes, and cleaning to be done. Most of this work was required every day regardless of the numbers of customers stopping in.

The roadhouses also generally had a few outbuildings for various purposes, the most important of which was a stable for horses to rest and recover. There was a change of horses at the roadhouses so that each new leg of the journey was started with fresh horsepower. There was no schedule for the roadhouse stops as the road and weather conditions dictated how far the stages could go in a day.

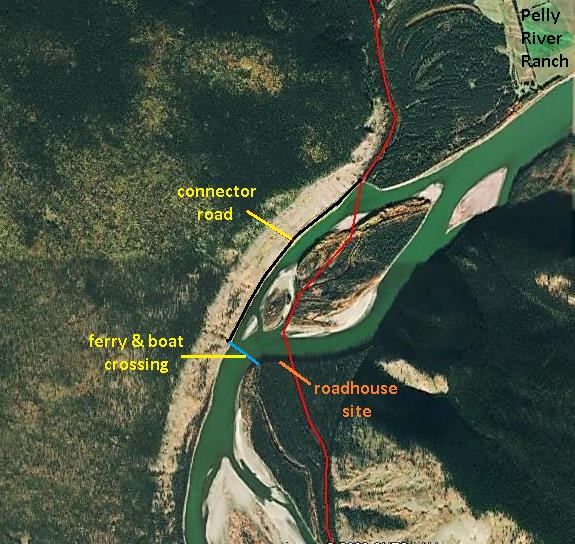

The roadhouses at the four major river crossings of the Overland Trail (Takhini, Yukon, Pelly and Stewart) had an additional stable located on the opposite side of the river from the roadhouse. At freeze-up and break-up of the river when horse teams and stages could not cross, the mail, freight and passengers would be transported by boat or canoe to the other side where horses and a stage kept at the stable enabled the trip to carry on.

Later, ferries powered by the river current were installed at the crossings to carry the horses and stages across when the river was mostly free of ice and the road was solid enough for use. These ferries ran along a cable that was suspended between wooden towers on each side of the river at a height that would allow boats to pass under.

A good synopsis of the Overland Trail and the operation of the roadhouses along it can be found in a Yukon Government publication at The Overland Trail | Government of Yukon.

The Old Pelly Crossing Roadhouse Site and Area (1902 – ca. 1924)

The Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse was an important one because of its location at a river, where additional infrastructure and sometimes personnel were required to deal with difficulties and delays often caused by river and ice conditions. For a time the roadhouse also served as the post office for Fort Selkirk, which was a few kilometers off of the Overland Trail, and occasionally housed North-West Mounted Police members who patrolled the Trail.

In the area of the Pelly River crossing, the Overland Trail approached from the south along the east side of the Yukon River valley and up about four kilometers of the Pelly River. The final 1,200 meters of the road ran through a timber-covered river flat of not great height above the river level and emerged at the river where the roadhouse was located.

(Natural Resources Canada, #75748)

(Yukon Archives, Robert Coutts fonds, Acc. 86/15, #99 – photo has been cropped)

(Gord Allison photo)

From the roadhouse location at the river, the winter road crossed over to an island and then to a river flat on the north side that also contains the Pelly River Ranch. This route went around the impenetrable basalt cliff across from the roadhouse that was formed by a lava flow from Volcano Mountain, 11 kilometers to the north. The road continued northward up a small creek valley away from the Pelly River valley and on toward the Stewart River.

(Google Earth)

During the shoulder seasons, the Pelly River was crossed with a boat or the ferry at a different location than the regular winter route over the island. This crossing was where the river narrowed below the island and necessitated the cutting of a connector road into the base of the basalt cliff. This road followed along the edge of the river and joined the normal route near where the latter came off the river and onto the bank. It is the remains of this road that the Bradleys of Pelly River Ranch would often point out on boat trips.

(Google Earth)

(Gord Allison photo)

The End of Old Pelly Crossing Roadhouse

In the early 1920s a new road was built to Mayo from the Overland Trail at Minto, 40 kilometers south of Old Pelly Crossing, in response to the increased silver mining activity in that area. This road headed northeast from Minto to present-day Pelly Crossing and beyond to near present-day Stewart Crossing, where roads then branched northeast to Mayo and, later, northwest to Dawson.

These roads soon became the busier routes, bringing about the abandonment of the Overland Trail north of Minto and therefore the need for the roadhouse at Old Pelly Crossing. Its last operators, Alex and Margaret Shaver, relocated to the new crossing of the Pelly River, likely in 1924, and ran a roadhouse there.

The Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse had been built on an outside bend of the river where the bank was being continually eroded away by the current against it. The remnants of the roadhouse and associated buildings were gone within a decade or a little more of it being abandoned, washing into the Pelly River in the 1930s.

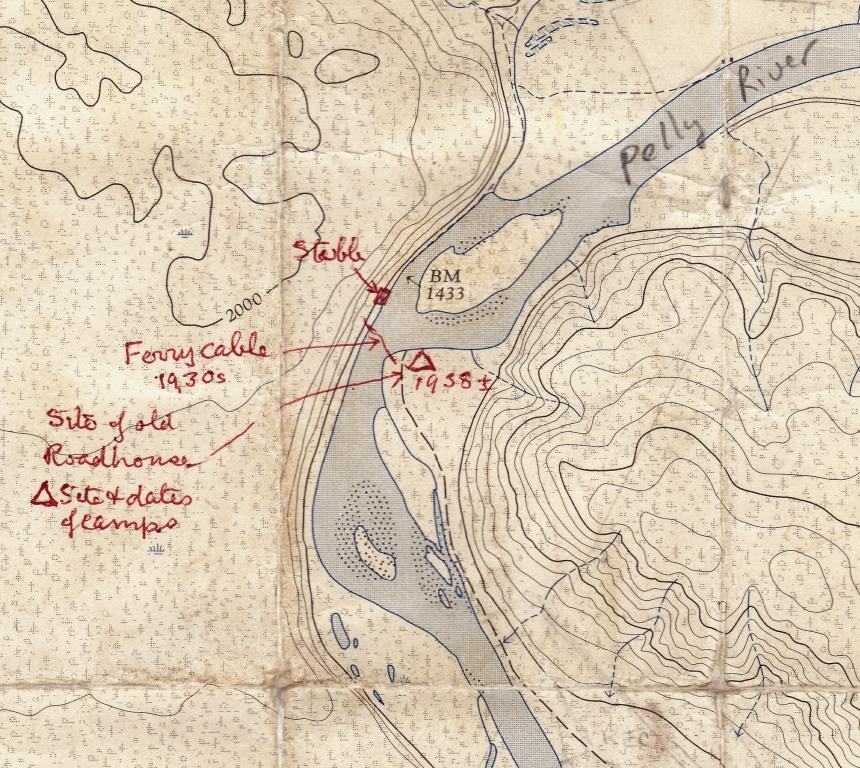

In 1932 the geologist Hugh Bostock camped on the site and reported that “the Pelly had already cut away some of the bank and taken some of the buildings”. In a 1985 letter to Lew Johnson, former resident of Stepping Stone about two kilometers south of the roadhouse site, Bostock said that he believed the roadhouse had burned down, but the ruins of where it had been were still apparent in 1932.

(Natural Resources Canada, #79333)

(Gord Allison photo, 2014)

Bostock also recorded in 1932 that the ferry cable across the river was still up, supported by the high wooden towers on each side of the river that kept the cable suspended above the river. The stable on the north side that was for housing horses during the freeze-up and break-up season was also still there. In 1949 on a return visit, he noted that the clearing that had marked the site of the roadhouse and the ferry cable tower, the stable, and much of the road along the north side of the river had all been washed away. In his letter to Lew Johnson he included a portion of a topographic map with notations he made of the approximate locations of these structures.

(Gord Allison collection, from Lew Johnson)

Bostock said that there was a major flood in 1935 that changed much of the course of the lower Pelly River. This may have been the year when a lot of loss of riverbank in the area of the roadhouse occurred. That year Alex Coward, a resident of Fort Selkirk, took the cable down, perhaps because it was a hazard to navigation or soon would be.

By comparing the oldest air photo available (1949) with the present condition, I estimated that the riverbank has been cut back about 150 meters in that time. This is in line with the Yukon Government’s land mapping tool (diagram below) showing that the north ends of the lots surveyed in 1903 for the roadhouse and the North-West Mounted Police reserve are now well into the river by a similar distance.

(Yukon Government Lands Viewer)

The northern boundaries of these lots were also set back 30 meters from the ordinary high water mark (OHWM) of the river at the time, so the riverbank location when the survey was carried out may have been on the order of 180 meters north of where it now is. That would put the 1903 riverbank in the vicinity of the present downstream ends of the islands in the diagram.

Hugh Bostock observed in 1949 that the main channel cutting its course southward into the riverbank where the roadhouse had been was also allowing the islands to ‘grow’ on their downstream ends. What all this means is that the roadhouse site is now far out into the river, and any metal remnants that may have settled onto the river bottom will likely be overtaken by further island development.

The Roadhouse Operators

The Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse had a number of operators over its years, three of them couples and the others single men. During the tenure of two of the women, the roadhouse seemed to be the party place for the Fort Selkirk/lower Pelly area. Hugh Bostock, who spent many years traversing the central Yukon in the 1930s and ‘40s in the course of his geological work, remarked that “the ladies of the roadhouses were quite remarkable characters”.

Thomas and Norah Whelan (1902-1904)

The Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse was established by Thomas Whelan, captain of the White Pass & Yukon Route steamboat Victorian. He was born in England in 1869 and began his mariner career there on the Thames River before immigrating to the United States. In 1892 in Washington state he married Norah O’Leary and they had a son Jack the following year.

The Whelans moved to British Columbia where Thomas became employed with the Canadian Development Company and began a decade-long association with the Victorian. When the Klondike gold rush began he was aboard the vessel for the “epic journey for flat-bottomed sternwheeled river steamboats” to St. Michael, Alaska, and then up the Yukon River to Dawson City. At some point in the Yukon, Whelan became captain of the Victorian.

Captaining a steamboat was seasonal work when the rivers were open, so for winter occupation he established Captain Whelan’s roadhouse (also known as Canadian Development Company Post #10 and Uncle Tom’s Cabin) on the Yukon River winter trail connecting Whitehorse and Dawson. His roadhouse was on an island in the river 17 kilometers downriver (north) from Fort Selkirk and was operational by at least 1900, when it appears to be a fairly new building in a photograph.

(Yukon Archives, H.C. Barley fonds, Acc. 82/298, #4924)

In 1901 Whelan became a White Pass & Yukon Route employee when that company bought out the Canadian Development Company and its fleet of steamboats, as well as taking over the year-round mail contract. In 1902 White Pass was contracted to construct the Overland Trail between Dawson and Whitehorse, and along with it established new roadhouses to support its mail, freight and passenger service. Where the Canadian Development Company had used dog teams for mail delivery on the Yukon River winter trail, White Pass’s service on the Overland Trail would be with the use of horse-drawn sleighs and sometimes wagons (the term ‘stage’ was used for both).

The construction of the Overland Trail meant the end of the river trail, other than for local traffic, and therefore the end of most of the roadhouses along it. This included Captain Whelan’s Yukon River island roadhouse, and he prepared to move with the times.

Whelan’s application in July 1902 for land for a roadhouse (likely selected with advice from White Pass) was on a moderately high spruce-covered bank on the outside of a bend on the Pelly River. It seems odd that a river man would pick a site that would be subject to erosion by the river, but perhaps the potential for that wasn’t as severe or evident at the time.

The land application was approved in August, and given Whelan’s summer employment on the river, it is assumed the roadhouse was built for him, perhaps with the support of White Pass. It nevertheless must have been a busy summer for the captain moving what was needed from his island roadhouse and making plans and arrangements for running the new place once the river froze over.

On top of this, Whelan’s wife Norah was expecting their second child, but this took a tragic turn on September 20, when their baby daughter Mamie contracted an illness after birth and died at two days old in Whitehorse. She was buried in the Pioneer Cemetery there.

Thomas and Norah must have had to put their misfortune behind them fairly quickly and get on with their winter preparations. This was normally facilitated by White Pass, which delivered horse feed and other supplies to the roadhouse locations by steamboat in the fall.

The Whelans were presumably operating their roadhouse when the first White Pass & Yukon Route Royal Mail stage on the new Overland Trail passed by a few days and 317 kilometers after it left Whitehorse on November 2, 1902. Two months later, on January 13, 1903, the roadhouse was a polling place for the Yukon general election.

(Yukon Archives, Emil Forrest fonds, Acc. 80/60, #10 – photo has been cropped)

The Overland Trail was a winter road only, as the Yukon River became the highway between Whitehorse and Dawson after it was free of ice in May. Most of the roadhouses shut down at this time and the operators usually went elsewhere for the summer. Thomas Whelan went back to captaining the Victorian, but it is not known where Norah and their son Jack went for the summer.

In early August 1903, the Dominion land surveyor Charles MacPherson arrived at the roadhouse in the course of his survey of the Overland Trail. He surveyed out the 20-acre roadhouse lot for Whelan, which would allow him to apply for the patent (title) to the land. McPherson also surveyed out an adjacent 40-acre parcel for the North-West Mounted Police, who planned to establish a post there.

The police reported that year that Whelan had a telephone line put in from the roadhouse to the telegraph office at Fort Selkirk in order to have contact with the outside world. Later, in about 1909, Frank Chapman of Pelly Farm extended this line from the roadhouse across and up the river to his farm in order to have communications there as well.

In December 1903 Whelan was notified that the remainder of the purchase price of his land was overdue, and so Norah sent the payment on the next stage, signing her covering letter as ‘Mrs. Capt. Thos. Whelan’. The next month they were requested to pay $1.75 in interest for the late payment and she again signed the letter the same way, adding that the Captain was ‘outside’ (of the Yukon). She was likely not on her own at the roadhouse, as there was normally a man stationed at the White Pass roadhouses to manage the stable and horses. She would also have had regular contact with North-West Mounted Police members who provided a daily mail service between Fort Selkirk and the roadhouse.

The break-up of the Pelly River ice in the spring of 1904 brought troubles to the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse. On April 30 stage driver Ernie Burwash arrived from Dawson at the stable across the river from the roadhouse, where he left his team and came across by boat so that the mail could be taken south on another stage waiting at the roadhouse. That evening the ice running in the Pelly River jammed up at the junction with the Yukon River, backing the water up. The roadhouse was flooded to several feet deep and the people had to scramble out, including the Whelan family who went and camped on a nearby hill. The stage drivers canoed across the river to the stable and tried to release the horses, but seven ended up drowning.

Whether this incident was a turning point for the Whelans or their departure was already planned, the flooding event is the last record of them at the roadhouse they had established. Thomas Whelan did not get his Certificate of Title to the land until July 1905, and it was a full year after that before he transferred it to the next operator of the roadhouse.

Whelan remained working on the steamboats for the next four seasons and may have spent the winters in Victoria with his wife and son, where they had a house. He left the Yukon for good at the close of the steamboat season in the fall of 1907, moving to BC where he worked the summer of 1908 on the Skeena River.

Norah Whelan was dealt her second blow in February 1909 when her husband’s body was found floating in Burrard Inlet in Vancouver. There were no witnesses to what happened to Thomas Whelan and his death was ruled to be accidental drowning. He was 40 years old when he died and said to be a genial and popular steamboat captain.

Harry and Bertha Hosking (1904-1908)

The next record of the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse after the Whelans is from the Royal Northwest-Mounted Police in July 1905, when members on a trip up the Pelly River stopped to check on ‘Hoskins Roadhouse’ that was closed up for the summer. This suggests that Harry and Bertha Hosking, who followed the Whelans, had operated it for the 1904-05 winter season.

Bertha Faas from Michigan was a young mother separated from her husband when she and her 8-year old son Joseph were living in Whitehorse in late 1901. In September 1902 she and Bud Harkin took out a marriage licence, but tragedy struck the following May of 1903 when Bud drowned on a canoe ride through the Whitehorse Rapids. Bertha later met Harry Hosking, an Englishman who had come to the Yukon in March 1900 and was employed as a miner in the Klondike goldfields. In September 1904 Harry and Bertha applied for a marriage licence in Dawson, but whether they actually married is uncertain.

Later in the fall of 1904 Harry and Bertha appear to have taken on the operation of the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse. Her son Joseph, who was then almost 11 years old and had changed his surname from Faas to Harkin, was recorded at the roadhouse at least once, but whether he lived there with Harry and Bertha is not known.

In July 1906 the ownership of the roadhouse lot was transferred from Thomas Whelan to Bertha Hosking. The following month, the Royal North-West Mounted Police again stopped in on their trip up the Pelly River to check on ‘J. Hoskins’ roadhouse and found all to be well.

In mid-November 1906, soon after the winter road operations had started up again, a mail stage broke through the Pelly River ice shortly after leaving the roadhouse. The rig stayed afloat and swung around with the current, the two lead horses getting tangled in the harnesses and drowning. The sleigh and other horses were able to be saved, and in the commotion of it all Harry Hosking had to be rescued from being swept under the ice.

(Yukon Archives, Charles Coghlan fonds, Acc. 83/19, #47 – photo has been cropped)

For the winter of 1907-08, the Royal North-West Mounted Police noted in its annual report that the constable stationed at Fort Selkirk moved to the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse for the winter to be located on the Overland Trail where most of the traffic was. This may have occurred in some other winters as well.

Newspaper articles from late 1907 and early 1908 show that Bertha Hosking was quite an entertainer, with any event seeming to be a reason for a party. She hosted a Christmas 1907 dinner at the roadhouse, with almost 40 people attending from Fort Selkirk, Pelly Farm, the Swinehart Farm, and Carpenter’s roadhouse up the Yukon River. Included were her 14-year old son Joseph, eight girls from the Horsfall and Breaden families of Fort Selkirk, and a couple of the White Pass stage drivers who found themselves at the roadhouse on Christmas Day. Bertha had ordered in turkeys from Vancouver and served these in addition to moose and caribou. The partiers danced until long after midnight before returning over the ice (or in the Carpenters’ case, south via the Overland Trail) to their respective homes.

Less than a month later on January 20, 1908, the Hoskings held a Leap Year dance at the roadhouse, with many of the same attendees and a number of First Nations people. A dinner and a midnight lunch were served, with dancing that went on through the night until daylight, which would not have been until the late morning. The Fort Selkirk farmer William Swinehart was the caller for the square dancing, with his son Guy and daughter Leta Stillman providing mandolin and guitar music. When the guests departed for their homes, the temperature was -63° F (-53° C).

In February the Hoskings hosted two birthday parties, one for Bertha’s 33rd birthday and the other for farmer and miner Guy Swinehart’s 26th. Many of the usual attendees were there and a few White Pass stage drivers were as well, raising the question if the drivers timed their trips to arrive at the Hoskings’ roadhouse on the party nights. The newspaper article about the birthday parties concluded with: “the Crossing has eclipsed all previous winters for festivities and good cheer … another party is planned to commemorate the going out of the ice”. Harry and Bertha Hosking obviously did their part to shorten up the long winter for their friends and neighbors.

The good time parties over the winter of 1907-08 were to be the last ones thrown by the Hoskings at the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse. In August 1908 Bertha was in Whitehorse on her way out to Vancouver and said that she would not be back in the fall. In October she transferred her title in the roadhouse lot to John McFarlane and George Brown.

Bertha did return and she and her son Joseph Harkin lived in Dawson with Harry, who had resumed his involvement in mining. In October 1917, at about the same time Joseph was being discharged from World War I service in Europe, Harry and Bertha left the Yukon to settle in Seattle. By the time of the 1920 US census, Bertha appears to have separated from Harry, but in 1922 they were back together and were married in Vancouver. This means that either they had never legally married before or had gotten divorced at some point.

Harry Hosking died in Edmonton in 1937 at the age of 62, and in 1941 in Vancouver 66-year old Bertha married George Howes, a 65-year old bachelor who had been an Overland Trail stage driver. He had attended at least three of the described parties that Bertha had thrown at the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse more than 30 years previously. Bertha died a widow in Seattle in 1950.

George Brown and John McFarlane (1908-1910)

After Harry and Bertha Hoskings’ tenure at the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse, information on its operation is sketchy for a few years. George Brown and John McFarlane gained title to the Old Pelly Crossing lot from Bertha Hosking in October 1908 and presumably ran the roadhouse that winter. Four months later, in February 1909, the title was solely in Brown’s name, so perhaps McFarlane didn’t stay there long, if he had at all.

(Dawson Museum, #1984.115.6)

In January 1910 the ownership of the lot was transferred to Edward Menard of the Pelly Farm, and that same month a newspaper article referred to George Brown as “formerly roadhouse keeper at Pelly River”. From the bits of information available, it can be inferred that Brown and/or McFarlane ran the roadhouse for the 1908-09 winter and Brown for perhaps part of 1909-10.

George Brown married Hazel Mack from an early Carmacks area mining family in 1913. Hazel operated the roadhouse in Carmacks, and when she died in 1925 George took over running it. He also went on to establish a successful farming enterprise near Carmacks growing vegetables and hay and raising livestock. He died in Whitehorse in 1943.

Edward Menard (1910-1912?)

Edward Menard was in his early 20s in June 1899 when he arrived in Dawson from Quebec . He ended up at Fort Selkirk and by 1901, along with George Grenier, started the Pelly Farm (now known as Pelly River Ranch) two kilometers up the river from the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse.

In January 1910 the roadhouse land title was transferred from George Brown to Menard, so perhaps he wanted a change or some winter work away from the farm. This was also the time that the farm was beginning to transition to new owners.

William Watson, a brother of Matthew Watson of the general store in Carcross, was a telegraph operator at Fort Selkirk from the fall of 1910 to the fall of 1911. He said that he spent many enjoyable evenings at the roadhouse with Ed Menard, who would proclaim ‘open house’ for any reasonable occasion.

Menard stayed in the area for the summer, when the 1911 census for ‘Pelly Crossing’ was taken. This was for the lower Pelly River area and included people living at the Pelly Farm, so it cannot be determined if Menard was also at the farm or at the roadhouse. It is likely that once the roadhouse closed in the spring he went back to the farm for the summer work there.

Menard may have run the roadhouse for the following 1911-12 winter or it may have been the subsequent operators, Alex and Margaret Shaver. The title to the roadhouse property was not transferred to the Shavers until 1916, but it appears that they started operating it around 1912.

Edward Menard went on to do other things in the area, including working as a stage driver for White Pass. During the winter of 1917-18 he was the stable man at the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse, then being run by the Shavers. Menard left the Yukon in 1921 and returned to St. Johns, Quebec, his prime years being spent in the Yukon and making a significant mark in establishing a farming enterprise that still operates to this day.

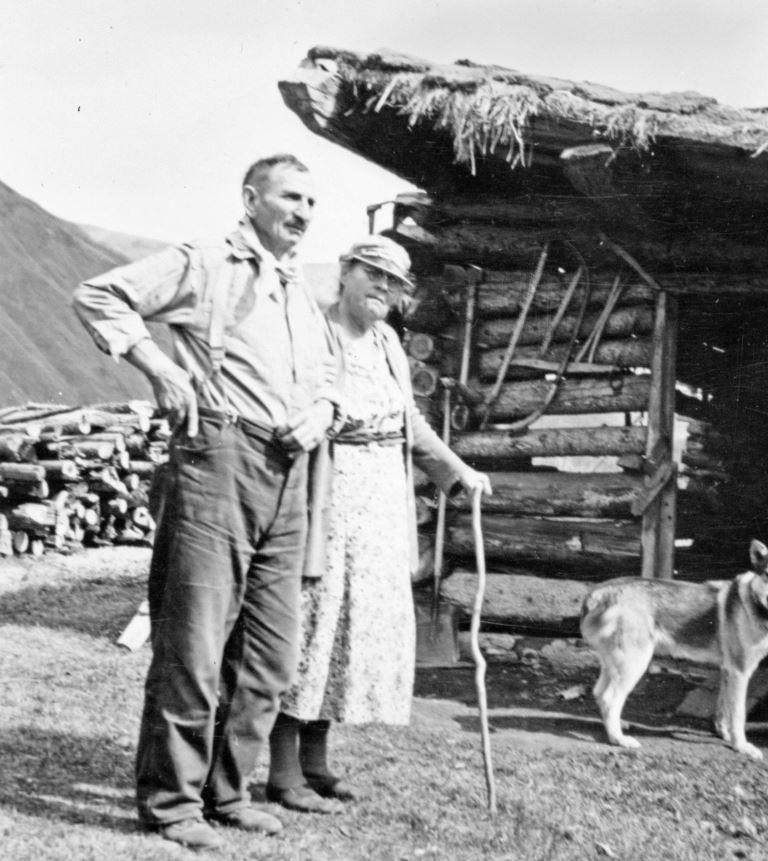

Alexander and Margaret Shaver (1912?-1924?)

‘Schaeffers Riffles’, the short section of faster water near the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse site, is a local name I have never seen written, but my writing of it is based on how it sounds when locals say it as well as the common spelling of that surname. It undoubtedly derives from a well-known couple who operated the roadhouse for a decade, and whose name appears in a variety of spellings. The most common seems to be Shaver, perhaps because it is the simplest.

Whenever Alex and Margaret Shaver took over the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse, it was the beginning of a tenure that lasted for half the time the roadhouse was in existence. ‘Mrs. Shaver”, as she was most commonly known, also made it a colorful time.

Alex and Margaret were born in 1866 and 1868, respectively, and were from Richibucto, New Brunswick. They left there as a young couple and took more than a decade to work their way west across the United States and north to the Yukon. Along the way they had three daughters, one born in 1887 in New Hampshire and two in Washington state in 1890 and 1892.

Alex came first to the Yukon in 1898, leaving his wife and daughters behind. He is listed in the Biographies of Alaska-Yukon Pioneers 1850-1950, where it says that he worked on building the Hepburn Tramway and Pioneer Hotel near Whitehorse. By the time of the 1901 census the remainder of his family had been in the Yukon for a year and a half and all were living about 150 kilometers up the Yukon River (south) from Dawson at Carlisle Creek, where Alex was a woodcutter for the steamboats.

Around this time the Shavers were also known to be operating a roadhouse at Thistle Creek, five kilometers downriver (north) from Carlisle Creek. That setting may be where Margaret began to establish her lively reputation. In his book After Big Game in the Upper Yukon, Nevill Armstrong of Russell Creek on the MacMillan River wrote about meeting the Shavers at this time: “one night … when paddling down the Yukon [River] … in bitter cold with a snowstorm blowing, we were thankful to strike the [Shaver] house where we found a hot stove and a drink of hot rum, and one of the pretty daughters beguiled us with tunes on her violin while we enjoyed a hearty meal”.

The Shavers ran the roadhouse at Thistle Creek for about the next decade, by which time they appear to have been looking for a change. In October 1909 Alex and Margaret along with their youngest daughter, also named Margaret, were in Whitehorse and the newspaper there reported that they were on their way to New Brunswick to reside.

Whether the Shavers actually went to New Brunswick and resided there for a while is not known. They do not show up in a search of the 1911 Canada census, but information has them in the Yukon in 1912. Perhaps their married daughters, Lina McNeill and Maud Edwards, and their families remaining in the Yukon were a factor in the Shavers not leaving or returning. That they did this led to future stories to come from the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse and later the roadhouse at present-day Pelly Crossing.

A couple of pieces of information indicate that the Shavers’ move to the Pelly River occurred by 1912. That year the Yukon government issued Alex ‘Shafer’ a winter licence for the Pelly Crossing roadhouse. Also, in the summer of 1912 Shaver entered into an agreement with George Grenier of the Pelly Farm for rights to some coal property Grenier had staked near the Yukon River about 12 kilometers south of the roadhouse. This then would appear to be the beginning of the Shavers’ time at the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse that would last for about 12 years.

(Glenbow Archives, #NA-1786-24)

If the Shavers did start operating the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse in the winter of 1912-13, they would have witnessed and probably hosted the people making the first motorized trip from Dawson to Whitehorse that December. A Guggenheim syndicate car that included Commissioner George Black as a passenger made this trip in 35½ hours of travelling time. In August 1918 a summer automobile trip on the winter road from Whitehorse to the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse was undertaken by Isaac Taylor of the Taylor & Drury stores and his family, but it is not mentioned if the Shavers were there at the time.

One year during the Shavers’ tenure at the roadhouse, the potential perils of the rivers during the freeze-up and break-up periods was made deadly clear. In early November 1915, a French-Canadian man named Tom Jeffries (with various other spellings) arrived at the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse with two log rafts, one with a tent pitched on it. Jeffries was a man of the bush (trapper, hunter, prospector) and had come down amidst the running ice from a hunting trip up the Pelly River. He visited at the roadhouse until late in the evening, then went out to sleep in his tent on the raft that was tied to a tree on the riverbank.

A little later a stableman working at the roadhouse went out and found that the ice had jammed up and covered the area where the rafts had been, carrying them away and leaving behind only the broken ropes that had secured them to trees. Edward Menard, a previous owner of the Pelly Farm as well as the roadhouse, was in the area and set out by canoe to try to find Jefferies, who was a friend of his. Menard located the raft near Kirkman Creek, about 78 miles down the Yukon River, with Jefferies’ body still in the tent. The body was clothed and lying on the bed, giving no indication of any sort of struggle or chaos, and it was therefore thought that Jefferies may have died of heart disease before the ice jam occurred.

In 1987 Lew Johnson, then owner of Stepping Stone on the Pelly River about two kilometers from the roadhouse site, interviewed Leta (Van Bibber) Israel in Sydney, BC. Leta had worked for the Shavers for five years, beginning in 1918 when she was 11 years old, until the roadhouse was abandoned and the Shavers moved to a new location at what is now called Pelly Crossing.

Leta described the roadhouse as a one-story building with a big kitchen and dining room, one wing that had rooms, and another section with two more rooms. She said that most of the people who came to the roadhouse were passengers on the White Pass stages, which would have been in the winter. In talking about her first summer there (1918), she said that the ferry ran, which presumably was for the few people who travelled the Overland Trail by foot.

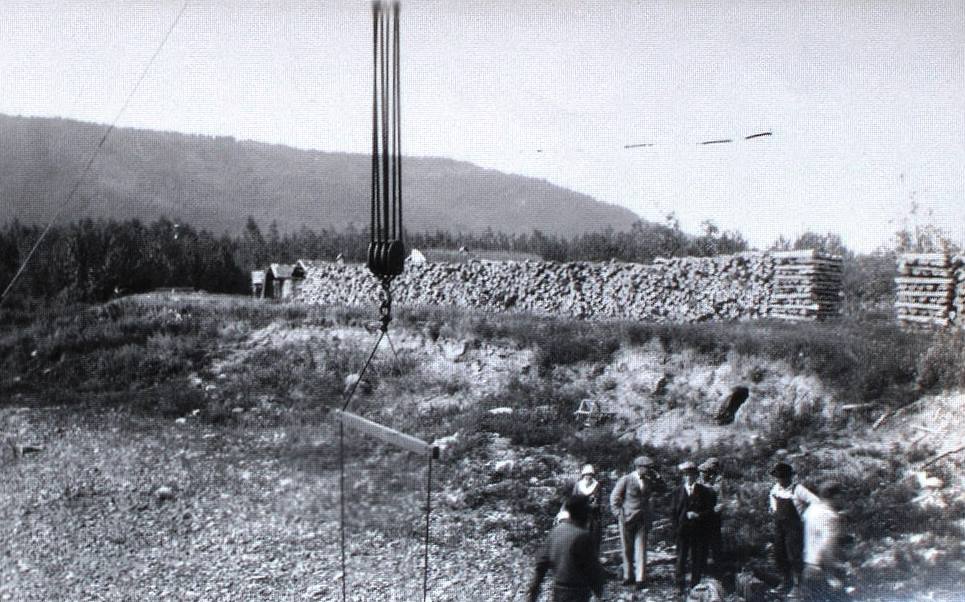

Leta also said that in the summer of 1918, Alex was gone from the roadhouse. His absence was likely due to his summer activities, as described by Nevill Armstrong in 1914: “[Shaver] is well known on the upper Yukon [River] as roadhouse keeper in the winter and cutter of, and dealer in, rafts or cordwood in the summer”.

The rafts refer to tree-length wood totalling many cords that were tied together and floated down the river to Dawson to meet the demand for firewood there. Much of this firewood came from the Pelly River, and Mrs. Shaver may have watched her husband float by their Old Pelly Crossing home on his rafts bound for Dawson.

(Yukon Archives, Kenard Knott fonds, Acc. 97/54, #46 – photo has been cropped)

The cordwood business that Shaver was also involved in was fuelwood for steamboats that was cut and hauled to the riverbanks and piled where the boats could pull up and load on large quantities of it. There were many such wood camps on the Yukon River and Shaver may have operated his in the vicinity of the Pelly River where he was close to home.

(Yukon Archives, Stuart & Edna Tompkins fonds, Acc. 84/12, #248 – photo has been cropped)

Leta Israel’s noting of Alex’s absence from the roadhouse in the summer of 1918 indicates that she and Mrs. Shaver stayed there during that time. Mrs. Shaver may have remained at the roadhouse most or all summers, unlike many other operators who went elsewhere when the roadhouses were closed in the off-seasons. In the 1921 census, taken in the summertime, the Shavers were enumerated on the Yukon River in the Fort Selkirk area, not the Pelly River as others such as the Pelly Farm people were. Perhaps she was staying or visiting at Alex’s wood camp when they were enumerated.

Leta told Lew Johnson a story related to her by RCMP Corporal Howard Cronkhite about stopping at Shavers’ roadhouse. Mrs. Shaver had a gramophone and loved to dance with whoever showed up there, including the Corporal. When the stage drivers came in, they would call her out of the kitchen to dance. She liked to chew tobacco and as she and her partner danced around the room, she spat into the spittoon as they passed by it. Cpl. Cronkhite’s period of service in the Yukon indicates that his experience with Mrs. Shaver would have been in her later roadhouse at present-day Pelly Crossing, but similar scenes undoubtedly played out at the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse.

John Scott, a Yukon mining engineer and hydroelectric developer in the middle decades of the 1900s, related a couple of stories he heard about Mrs. Shaver, “a large, tough, good-hearted woman”. She would get the stage crews and guests mobile in the mornings at the roadhouse by hollering things like “hurry up and come alive! I’ve got to have that sheet you’re sleeping on for a tablecloth!”.

In 1914 Alex Shaver applied for a 160-acre homestead about three kilometers south of the roadhouse, near the mouth of the Pelly River. It is unknown how much work he put into it, but in 1921 he gave it up because he felt he couldn’t comply with the homestead requirements. In the meantime, in 1916, the Shavers had the title to the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse lot transferred to them from Edward Menard. In 1921, after he had relinquished his homestead land, Shaver wrote to the government expressing interest in leasing some hay meadows to the east of the Yukon River between Minto and Fort Selkirk. All these actions suggest that he liked the area and wanted to stay there, but a new road to the east of them would soon draw him and Margaret away.

(Yukon Archives, GOV 1654, file 29589)

In 1921 the White Pass & Yukon Route gave up the mail contract and ended its Overland Trail operations, running its last stage that spring. The mail service was taken on by a smaller local contractor that soon shifted to mechanized equipment for hauling the mail and other freight, with passengers being a lesser priority. It appears that the Shavers remained at the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse for the next couple of years, perhaps running it independently.

A late April 1923 newspaper article about a trip from Mayo involving both horse teams and ‘cat’ trains tells of the drivers staying at Shaver’s roadhouse. They had come on the road from Mayo to Minto to get onto the Overland trail for Dawson. One of the men reported that “coming down, we had fine roadhouse accommodations after hitting Pelly, and especially enjoyed the fresh milk and the phonograph concert which Mrs. Shaver gave us at Pelly roadhouse. She certainly is a royal entertainer.” The fresh milk was undoubtedly a benefit of the proximity of the roadhouse to Pelly Farm.

In 1924 a new road to Dawson from near present-day Stewart Crossing was completed and the mail service planned to use this route for the following winter season. This would have spelled the certain end of the roadhouse at Old Pelly Crossing, and if there was an exchange of money in the previous transfers of the roadhouse and its land title, the Shavers would have had no such opportunity.

Alex and Margaret Shaver after Old Pelly Crossing

It is not known exactly when the Shavers vacated the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse and relocated the 55 kilometers to the east up the Pelly River to where the new road to Mayo and Dawson crossed it. By September 1924 they had moved into a building on land owned by Ira Van Bibber on the north bank of the river and were having it transferred into their names.

In late September 1925 Nevill Armstrong, travelling down the Pelly River from Russell Creek, stopped at the Shavers’ roadhouse at the new Pelly Crossing. There he found the Shavers and two of their daughters, 24 years after he had first met them at Thistle Creek on the Yukon River. Just as Armstrong and his companions had been entertained at that time, after dinner the gramophone was turned on and Mrs. Shaver invited them to dance with her.

(Yukon Archives, Bill Hare fonds, #6749 – photo has been cropped)

In October 1928 Alex Shaver was one of a number of Yukoners who lent the mysterious Russian cross-country traveller Lillian Alling assistance when he gave her a ride across the river at Pelly Crossing. Another notable event occurred the following January when an airplane piloted by the well-known Everett Wasson landed on the Pelly River in front of the Shavers’ roadhouse due to poor weather. It was the first landing of an aircraft at Pelly Crossing and Mrs. Shaver “was very pleased with the unique visit”.

Two months prior to that visitor from the sky, Margaret Shaver’s life had taken an unfortunate turn. On November 21, 1928, her husband was at the riverbank working on his boat motor when he collapsed into the boat from the effects of a stroke and lost consciousness. He was a large man and Margaret and another man who was there could not lift him out, but fortunately Ira Van Bibber came along and they managed to get Alex to the roadhouse.

Margaret was not able to get word out until the next day, and her husband passed away the following day, on November 23. Assistance in the form of an RCMP constable from Keno along with the Shaver’s son-in-law from Mayo travelling by dog team didn’t arrive until two days after the death. Alex’s body was put on the northbound stage for Mayo, where he was buried in the cemetery near the airport a few days later. He was 62 years old and had spent half of his life in the Yukon.

Mrs. Shaver continued to operate the roadhouse for a time with the help of her daughter Margaret Sullivan of Mayo. Another of Mrs. Shaver’s daughters, Maud Edwards, and her husband later ran the roadhouse for a number of years.

In 1932, at the age of 64, Margaret Shaver married Henry “Cy” Detraz (pronounced as ‘Detraw’), a farmer at Coffee Creek, 105 kilometers down the Yukon River (north) from Fort Selkirk. The geologist Hugh Bostock watched a large wood raft floating down the Pelly River one day and observed that “a large woman in a grand hat and luxurious fur coat sat in a rocking chair near the bow”. He later learned that this was Mrs. Shaver catching a ride to Coffee Creek to start her new life there. He said that “Mrs. [Shaver] was a well-known character of the country and it was some years before people were reconciled to using her new name … and to stop calling Detraz “Mrs. [Shaver’s] husband.””

John Scott, mentioned previously, had a story about Margaret at Coffee Creek when her husband and others were trying to load a bull onto a steamboat for delivery to Pelly Farm. The captain, hoping to amuse his passengers, yelled down to her “Mrs. Detraz, has that bull of yours got a pedigree?”, to which she held up her arm and replied “when that old bull gets excited he has a pedigree that big!”.

By the mid-1940s Margaret was in poor health due to diabetes and other ailments, and Cy had to do most of the domestic chores as well as the farm work. On February 15, 1946, his 78th birthday, he went out to fork hay and when he didn’t come in for lunch, Margaret made her way out to where he was working and found him lying on the ground, deceased as a result of a heart attack. Cy Detraz was buried on a bench overlooking the homestead at Coffee Creek he had established 35 years before.

(Yukon Archives, Van Bibber Family fonds, 87/80, #43 – photo has been cropped)

After a couple of days wait, a plane came in and took Mrs. Detraz to Dawson where her daughter Lina McNeill lived. After a few months staying in Dawson she went to Carcross where her daughter Maud Edwards was then living.

The 1940s was not a kind decade to Mrs. Shaver/Detraz. It brought the deaths of her youngest daughter Margaret Sullivan in Vancouver in 1942 at the age of 50, her 36-year old grandson Alexander McNeill in Dawson in 1945, and then her second husband Cy Detraz in 1946. She would soon follow them all when she passed away on April 23, 1947 in Carcross at the age of 79. She was buried in the Pioneer Cemetery in Whitehorse, where her headstone spells her name Margarete, and her Findagrave.com information includes the name ‘Shaffer’, from an unknown source.

‘Mrs. Shaver’ dedicated almost 30 years to accommodating and entertaining people in Yukon roadhouses, and as Mrs. Detraz another 14 years as a Yukon River homesteader’s wife. This legacy is left for her descendants, a few of whom I believe are still in the Yukon.

The Closing

Schaeffer’s Riffles still bubble away in the Pelly River, and shortly before entering them going downstream you might boat over a few remains of the Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse on the river bottom beneath you. On the nearby land, there are only a few physical indicators of where the roadhouse once stood. One of these is a patch of younger trees marking the roadhouse lot that was cut out for timber. This is difficult to observe from river level, but is fairly evident from above.

Another indicator is the footprint of the Overland Trail on the south side of the river, adjacent to the roadhouse lot. When you pass by there on the river, for a brief instant you may spot a narrow opening through the trees heading away from the river. This was the Overland Trail that came to the roadhouse from the south, and as the years go on this opening is becoming increasingly harder to see.

(Gord Allison photo)

The Old Pelly Crossing roadhouse was a hub of activity along the Overland Trail during the winters for over two decades in the early 1900s and the home for several people who operated it. The site where it stood is now Pelly River bottom and any remnants that are left of it lie there. Many river travellers who pass through the area may be unaware of this history, but the stories remain for those interested in seeking them out.

My thanks to Lew Johnson and Dale Bradley for providing information and feedback for this article.

Updated April 10, 2025

Links to related articles: The Dawson-Whitehorse Overland Trail – Overview and The Overland Trail: Stewart River to Pelly River

©Yukon History Trails – Gordon Allison 2022

Very Interesting Gord. I enjoyed that read. Thanks a bunch for all your research.

Thank you Dorothy. I thought of you many times while writing this story. It and some others wouldn’t have happened without you and Ken coming into my life.

Thanks for all the research and writing Gord! Fascinating glimpses of life in the area! Be sure to stop in when you are in the neighbourhood.

Thanks very much, Jim, it’s my pleasure. I’ve appreciated your hospitality when I’ve stopped by and hope to do it again before long.

Very interesting story Gord and extremely well documented and presented. Missing out on your storied history is never part of my plans.

I always appreciate hearing from you, Boyd. Thanks for taking the time to comment. This was an enjoyable story to do.

Gord, another excellent effort grubbing into the deep soil of Yukon History. You unearthed some fascinating history of a modest road house that seemed to be the social gathering place just outside of town for the residents of Fort Selkirk in the early 1900s. There may have been some bootlegging according to some old stories I heard. I did find a very old style, heavy bottle that was once sealed with a cork on the top of the escarpment near an old trail that once led off the basalt down to the river across from the roadhouse site.

Thank you, Lew, and particularly for the information and insights you provided to make this story better. I have heard that there was a short-cut trail over the escarpment between Fort Selkirk and the roadhouse. It would have been used when the rivers were open, so required a raft at either end. This might mean there was somebody at the roadhouse in some summers more than we thought. If so there may have been some bootlegging going on.

Imagine throwing parties so good that they are published in the news and read about over a century later! I love the image of Margaret Shaver in her rocking chair floating down the river on a log raft.

People came from several miles away on foot or dogsled over the Yukon and Pelly River ice to attend those parties. One of the parties reported was in -60F temperatures, so they must have been good. And for Margaret Shaver, too bad that Hugh Bostock, who witnessed and wrote about her raft ride, didn’t take a picture. That would have been one of a kind. Thanks, Alida.

Another great read Gord. I don’t know how I missed this one. So many ‘larger than life’ characters have made their way and and then their lives in the Yukon Territory. Thanks

Yes, a lot of people who came to the Yukon and stayed to make an imprint here. Thanks for the comment, Rob.