Olsen’s Disappearance

While O’Brien was on his southward journey away from his grisly crime, the NWMP were becoming increasingly busy looking for Fred Clayson, Linn Relfe and Lawrence Olsen. It started with Cpl. Ryan at the Hoochekoo post, where Olsen did not show up for Christmas dinner as expected.

Ryan wondered what had happened to Olsen because he viewed him as a reliable man. The nearest telegraph station was at Five Fingers, 16 miles to the south, so Ryan did not have the benefit of that means of communication. He considered the possible explanations, such as an accident in the bush, falling through the ice, more breaks in the telegraph line to take care of, or even that Olsen was following a tip about a new gold discovery.

Two days after Christmas a member from the Five Fingers NWMP post came to Hoochekoo saying that they had not heard from Olsen. Ryan and a dog driver quickly set out on the river trail northward, searching along the telegraph line as they went for any sign of Olsen. About eight miles south of Old Minto, they left the river and took the Pork Trail because it followed along closer to the telegraph line.

An impediment to this was a recent heavy snowfall that made travel difficult and obscured tracks and other signs. Despite this, at a point nearer to the north end of the Pork Trail, Ryan managed to make out the faint impression of a trail beneath the new snow cover leading away from the Pork Trail. He followed it back into the bush and came upon the tent that had been the temporary quarters of O’Brien and Graves.

As it was near the end of the day, Ryan and his dog driver went to Fussell’s roadhouse to spend the night. There they learned that Olsen had left the roadhouse with Clayson and Relfe on Christmas Day, headed for Hoochekoo. Olsen’s disappearance now looked like it was not accidental nor intentional, at least not on his part.

The next morning, Ryan and the dog driver went back to the tent to investigate. Inside was a bunk for sleeping, a stove, and a number of items including a rifle hanging from the roof of the tent. There were also goods marked as McKay’s, obviously stolen from the cache less than a mile away. Ryan decided it was time to involve Pennycuick, who he viewed as “a very clever policeman”, and informed him of the tent discovery.

(Library & Archives Canada, RG18, Vol. 254, File 318)

On January 3, 1900, about the time O’Brien was at or nearing Tagish, Pennycuick wired NWMP headquarters in Dawson City requesting that all posts along the river trail be on the lookout for two suspected cache thieves using the names Miller and Ross. Pennycuick then departed Fort Selkirk for Hoochekoo to meet with Ryan, stopping at the tent on his way where he saw that the stove had the same figure-eight holes in the stovepipe that he had previously observed at the Hell’s Gate camp.

Pennycuick returned to Fort Selkirk on January 5 and found a message saying that enquiries were being made about a Frederick Clayson, who was overdue at Skagway. Pennycuick wired to Dawson that three men had left Fussell’s roadhouse together on Christmas Day and two of them, Olsen and Clayson, were now known to be missing. He also noted that the men calling themselves Miller and Ross had not yet been found, and this time he mentioned that they had two dogs, one of them a big yellow dog.

O’Brien’s arrest at Tagish

It likely was not part of George O’Brien’s plan to go near the NWMP post at Tagish, but he ended up there after his horses went through some ice nearby and into the water. He took them to the post barracks, perhaps thinking the stable there was his only option to get the horses dried off and warmed up. While there he was found to have a police-issue winter fur robe in his possession, which he said he had gotten as a replacement when the police in Dawson misplaced his. He was detained while Sgt. George Graham sent a telegram to Dawson to verify this, and in doing this Graham provided details about O’Brien including the big yellow dog.

A return telegram later that day confirmed that O’Brien had been in the Dawson jail and was given a government fur robe there. Sgt. Graham had no reason to hold him any longer and he was released, intending to leave for Skagway the next day.

Somebody in the Dawson NWMP noticed a link between the wire Graham had sent to Dawson and the earlier one that Dawson had sent with Pennycuick’s information. Both mentioned the big yellow dog of a type distinctive enough that people took notice of it and remembered it. This connection resulted in another telegram from Dawson a few hours later instructing Graham to arrest O’Brien on suspicion of cache theft.

That evening, Graham sent Constable Thomas Dickson into the Tagish village to arrest O’Brien. This may be the arrest, or one of them, that Dickson is known in family lore to have issued the command “hands up or your lights out”. Dickson would go on to marry Louise George at Tagish, raise a large family in the Kluane area, and spend the rest of his life in the Yukon.

For George O’Brien, Tagish was as far south as he would get. He was held by the NWMP there for another month and a half before being taken back north along the Yukon River trail to Fort Selkirk to face the cache theft charges that had been made against him.

Pennycuick and Ryan Investigate

By this time, the newspapers in Dawson City were pressing the NWMP for information about the missing men. Though the NWMP had little to say other than that they were working on it, as early as January 9 the Dawson Daily News was asserting that the men were murdered along the trail. On January 12, the NWMP assigned more resources to the case by putting Inspector William Scarth in charge of the investigation. He established his base at Fort Selkirk and instructed Cst. Pennycuick and Cpl. Ryan to do the ground work.

Pennycuick spent the next couple of weeks gathering information about the movements of Clayson, Relfe, Olsen, O’Brien and Graves from people who had encountered them along the river trail and at roadhouses. By January 24, enough connections had been made to suspect the man being held by the Tagish NWMP, George O’Brien, of having some involvement in the disappearance of Clayson, Relfe, and Olsen.

Near the end of January Pennycuick and Ryan set up quarters in the same Arctic Express Company cabin that the men calling themselves Miller and Ross had occupied in mid-December, the last place they were reported to have been. Concentrating their efforts in the vicinity of the cabin, Pennycuick and Ryan investigated slight depressions in the snow that indicated old tracks and trails underneath. On February 19, after three weeks of following and digging out these trails, no clues were uncovered and they gave up the search in that area.

Detective McGuire Appears

Phillip Ralph McGuire was born in Pennsylvania in 1869, the seventh of 11 children. He left there in 1889 and by 1895 was in Minnesota, married with a daughter and working as a detective. When and why he went to Skagway is not known, but on February 15, 1900 he introduced himself at the Tagish NWMP post as a detective working on behalf of Frederick Clayson’s brother William.

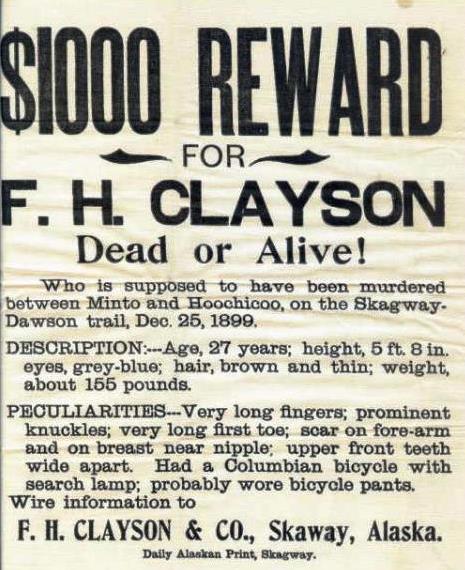

Possibly in conjunction with McGuire’s investigation into Frederick Clayson’s disappearance, the Clayson family had reward posters made up and distributed. They were made of cloth material and had a small photograph of Frederick Clayson attached to them with a paper clip. The poster indicated that the family had by now accepted that Frederick had probably been murdered, a conclusion they likely came to based on a visit to the NWMP at Tagish and as well as on the newspaper stories.

Some sources, particularly newspaper articles, said that McGuire was with the famous Pinkerton detective agency, but he denied this, saying that he worked on his own. He was allowed to question George O’Brien and then said that he was heading along the trail to the Minto area to assist with the murder investigation.

McGuire with his two-dog sled team arrived at the Hoochekoo NWMP post about February 23 and there met Cpl. Ryan, who agreed to accompany the detective the next day to the Minto area. They spent several days poking around the area of the Arctic Express Company cabin, but again this yielded no results.

On March 1 things changed when they went to look at O’Brien and Graves’ tent in the bush. In the ashes of the stove, McGuire found some remnants that indicated somebody had been burning clothes, a strange thing to do. By this time McGuire was proving himself valuable enough to the short-staffed NWMP that they agreed to pay him to assist with the investigation.

O’Brien is Brought Back

About this same time, in late February or early March, George O’Brien was brought, handcuffed to his sleigh, by two policemen from Tagish to Fort Selkirk. His horses and dogs were brought along as well. He was first held at Fort Selkirk because the charge of cache theft originated from there, but in late March he was moved on to the jail in Dawson City.

A number of people along the way identified O’Brien as the man who had been hanging around the Fort Selkirk-Old Minto area in December with a partner. This included Cst. Pennycuick, who confirmed that O’Brien was the same man who gave his name as Miller in the camp at Hell’s Gate. Everybody also identified the big yellow dog that was with him.

The Murder Site is Found

On and off for the next few weeks, the investigators continued to focus on the trails in the area of the Arctic Express Company cabin. The heat of the sun in the longer March days was softening and settling the deep snow, so that older trails underneath it were becoming even more discernible as depressions in the snow.

On March 19 McGuire, working alone with his dogs, detected and followed the faint outline of an old and well-packed sled trail that led from the area of the cabin southwards and then across the river to the west side. It went directly to where the northern end of the Pork Trail joined onto the river trail. This was a strong indication that O’Brien and Graves had moved to that area, and it was time to concentrate the investigation there.

The next day McGuire went onto the Pork Trail and noticed the impression of a trail that branched off and appeared to head toward the river. He followed it along the edge of a bench for almost three-quarters of a mile to where it ended at the top of a cutbank beside the river. He then doubled back several hundred yards to a spot where he had noticed a blazed tree marking another trail that branched off.

He followed this trail down a moderately steep bank onto a flat, bushy area that was not a lot higher in elevation than the river. After a short distance the trail came out to the river about 500 yards north of where the other one had ended on top of the cutbank. McGuire didn’t know it yet, but he was now standing on the murder trail.

(Library & Archives Canada, RG18, Vol. 254, File 318)

As McGuire approached the riverbank, his husky dog became very agitated, sniffing around a particular area of snow. McGuire tied the dogs up and dug down in that spot, lifting and setting aside the overlying snow until he reached a packed layer further down. Here he found a large patch of frozen blood-soaked snow that was later determined to mark the death spot of Linn Relfe. McGuire continued to remove snow along the trail and as he got nearer the riverbank he uncovered another blood patch, this one marking the spot where Frederick Clayson had died.

On March 22, Cst. Pennycuick went with McGuire to see the blood discoveries. They then went to the top of the cutbank, which Pennycuick reasoned would be a good place for bodies to be dragged down and put under the ice. He was more convinced of this when he climbed down the bank and found some threads of clothing stuck on it.

As they returned back up the trail, Pennycuick observed that the trees cut to make the trail were done with a dull axe that had an identifiable nick in it. When they got to O’Brien and Graves’ lookout spot, they noticed the trees that had been cut to make the sightline to the river and that they had been cut with the same nicked axe. When they went to the tent site, they determined that the logs for the tent frame had also been cut with that axe. When it was later found, the axe that cut all those trees was identified as being among O’Brien’s effects when he was in jail in Dawson City.

Pennycuick had another revelation in store for that day. He had brought O’Brien’s big yellow dog with him from Fort Selkirk, where O’Brien was being held. At the lookout, he released the dog and said “go home”, to which the dog ran down the Pork Trail, turned up the trail to the tent in the bush, and laid down under a tree with a wire wrapped around it that a dog could be tied to. There was no doubt that the dog had stayed there, if only for a matter of days, but long enough for him to remember. This also meant that George O’Brien had stayed there as well.

Furthermore, Pennycuick and McGuire now knew that the trails that connected the tent to the cutbank and to the murder site, and a sightline made from the lookout, had all been cut out with the same nicked axe that had built the tent O’Brien and Graves had stayed in.

The Hands-and-Knees Search

If Clayson, Relfe and Olsen had indeed been murdered, no bodies had been found to confirm it. Therefore the only way to prove the case would be through a detailed search and gathering of physical evidence that would lead to that conclusion beyond a reasonable doubt. On March 23, Pennycuick and McGuire began a systematic and laborious six-week search of the murder and tent sites.

To make their work easier, Pennycuick brought three men from Fort Selkirk to move the search camp from the Arctic Express Company cabin to the murder area. This eliminated the three miles of travel twice a day that he and McGuire were doing to carry out their investigation. The camp was set up in the bush just off the river and within throwing distance of the murder site.

They removed snow down to the old packed level along the 100+ yards of murder trail, sifting through the packed layer and marking the locations of the evidence they found with labelled sticks. They recorded the finds in their notes and made measurements along the trail so that all the evidence could be plotted on a chart.

In addition to blood patches and spots, the following were among the many articles and other evidence they discovered at the murder site:

- 5 shells of the caliber of rifle that Ryan found in the tent;

- 2 shells of the caliber of revolver seized from O’Brien at Tagish;

- marks in trees made by bullets that had missed their mark;

- crown of a tooth found at second patch of blood, later matched up to Relfe during post-mortem; and

- a myriad of small items, many of which were traceable to the victims.

Pennycuick and McGuire also cleared snow around the area of the tent and found more items that were associated with the victims, including two keys identified by Clayson’s brother and shown to fit the safe in the Claysons’ store in Skagway.

(Library & Archives Canada, RG18, Vol. 254, File 318)

Pennycuick and McGuire measured the distances, using a surveyor’s tape, of all the trails involved in the murders. Pennycuick then prepared maps and sketches of the trails and of the murder site and tent site, as well as an overall map stretching from Hoochekoo in the south to Old Minto in the north. Cpl. Ryan later returned to the area and took photographs of the significant locations and views.

On May 4, the ground search ended after almost three months of investigations at the Arctic Express Company cabin area, the tent site, and the murder site. It was estimated that about 200 cubic yards of snow was moved, the equivalent of 20 dump truck loads, resulting in the collection of around 400 pieces of evidence.

The Bodies show up

After the ice went out of the Yukon River in mid-May of 1900, the NWMP and others were anticipating that bodies would soon appear. They were proven correct on May 30, when the first one was reported on a river bar a mile and a half south of Fort Selkirk.

Cst. Pennycuick recovered the body and took it to Fort Selkirk for a quick examination and putting into a wooden box, then transported it to Dawson City for an autopsy and inquest. There the body was identified as that of Frederick Clayson and that he had been killed by gunshot wounds.

The body was shipped from Dawson in a wooden coffin, then transferred into a sealed metallic casket at Skagway. Clayson’s mother and sister accompanied the body from Skagway to Portland, where Frederick Clayson was buried in the Lone Fir Pioneer Cemetery on June 28, 1900.

On June 8, a body was sighted near Hell’s Gate, 11 miles south of Fort Selkirk, and recovered three days later. It was taken to Fort Selkirk for an initial examination and identified as the body of Linn Relfe. The body was packed in ice and shipped to Dawson to undergo an autopsy and inquest where, as with Clayson, death was found to have been caused by gunshot wounds.

Linn Relfe’s friends in Dawson City had his body embalmed, sealed in a casket, and sent to Seattle. There he was buried in the Lake View Cemetery.

A third body found more than 30 miles down the river from Fort Selkirk was reported to the NWMP on June 26. It was transported to Dawson, where its physical features enabled it to be identified with confidence as the body of Lawrence Olsen.

Olsen was buried in the Hillside Cemetery in Dawson City on June 30, 1900. It is not known if the authorities learned any more about him or if they were able to contact any family.

Next: Part 4 (The Trial, the Sentence and Visiting the Site)