Finley Beaton lived for over 50 years in the Yukon, beginning with the Klondike gold rush in 1898, and spent more than 40 of those years along the Yukon River as a supplier of wood for steamboat boilers. He was also a homesteader for a few years, developing a small farm along the river. For most of these years, he did all this work without a right hand and lower part of his arm as a result of a gun accident.

I remember hearing about Beaton years ago when travelling along the Old Pelly Farm Road north of Minto with Dick Bradley of the Pelly River Ranch. He pointed out a smaller side road that led to a place on the Yukon River known as Beaton’s. When I began researching Beaton, I found out that he applied for land there in 1922, but also that the place had actually been started by Harris Welch in 1899. Further, it piqued my curiosity when I learned that Beaton was referred to as ‘the one-armed woodcutter’.

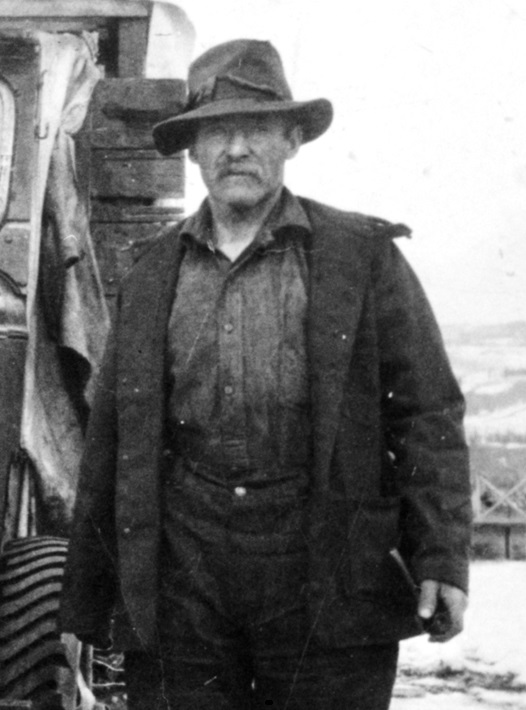

(Yukon Archives, Louis Irvine fonds, Acc. 82/295, #1902 – photo has been cropped)

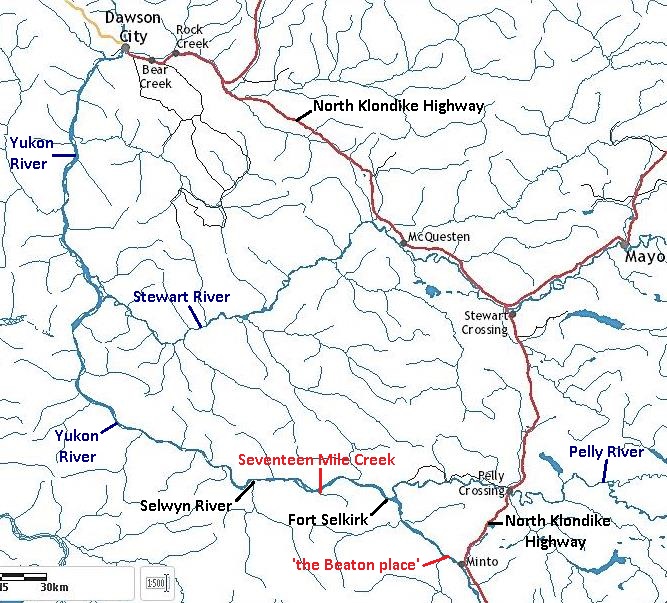

The first half of Beaton’s woodcutting career was in the area of Seventeen Mile Creek (not an official place name), about halfway between Fort Selkirk and the Selwyn River. The latter half of his woodcutting life was in the Minto area, including the site mentioned by Dick Bradley, which is still referred to as ‘the Beaton place’ and has an old standing cabin. My research involved visiting this place a number of times as well as finding Beaton’s cabin site from his earlier days further down the Yukon River near Seventeen Mile Creek.

(GeoYukon viewer)

Finley Beaton was born on March 31, 1872 in Inverness County on the west shore of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, the youngest of a dozen children in a farming family. His name appears as Findlay in a few places, including on his death registration and headstone, and also in some places as Finlay. However, he signed his name as Finley where I’ve seen it, so that is what I am using.

Beaton went to the northeastern United States as a young man and was a logger there when he heard about the Klondike gold rush in 1898. He headed to Vancouver, outfitted himself, and joined the thousands of other stampeders going over the Chilkoot Pass, building a boat at Lindeman Lake, and sailing down the Yukon River to Dawson City. He apparently spent some time on Eldorado Creek, but like many others he probably couldn’t get a gold claim of his own and so turned elsewhere.

Woodcutting in the Fort Selkirk – Selwyn Area, ca. 1900-1922

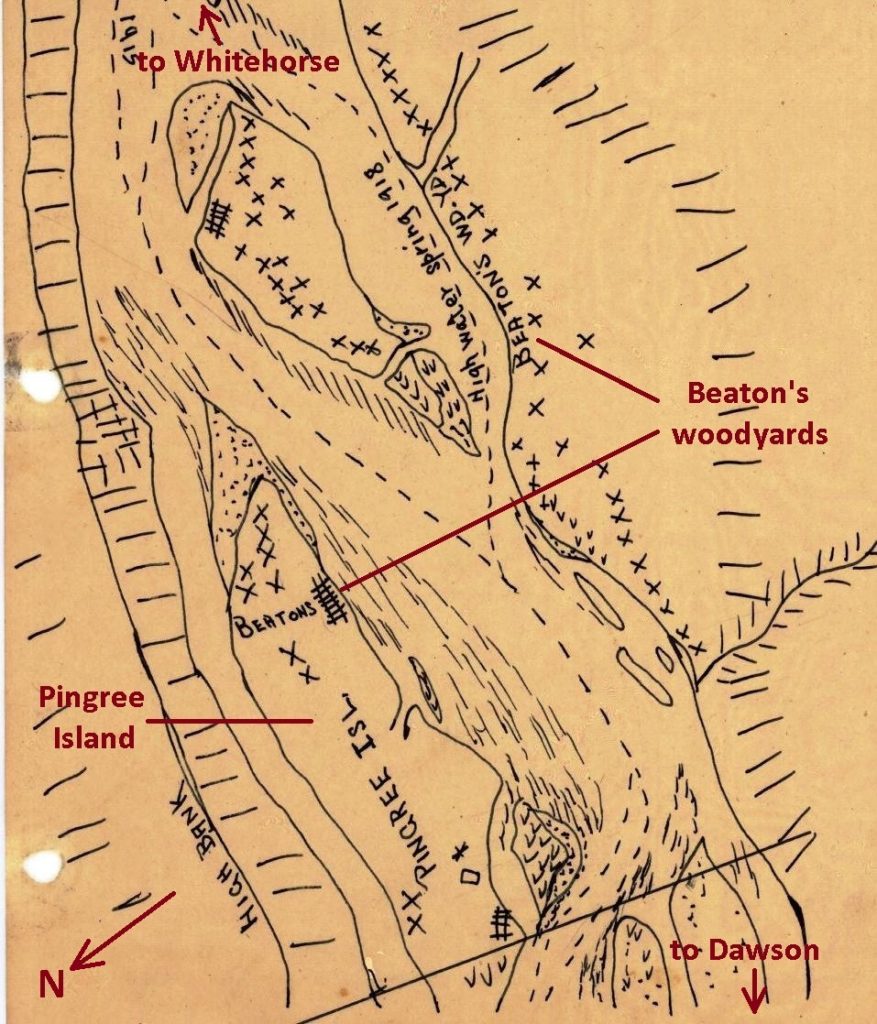

By 1901 Finley Beaton had returned to his vocation as a woodcutter (termed ‘woodchopper’ in those days) supplying steamboats on the Yukon River with wood for fuel. An old steamboat channel chart shows that he had woodyards about 150 miles up the Yukon River (south) from Dawson. These were in the area of Pingree Island, a mile and a half-long island 20 miles down the Yukon River from Fort Selkirk and 12 miles up from Selwyn River. He had a woodyard on the island and another on the bank of the river a short distance above the island, and perhaps others. Beaton would remain in this area for the next 20 years or so.

(GeoYukon viewer)

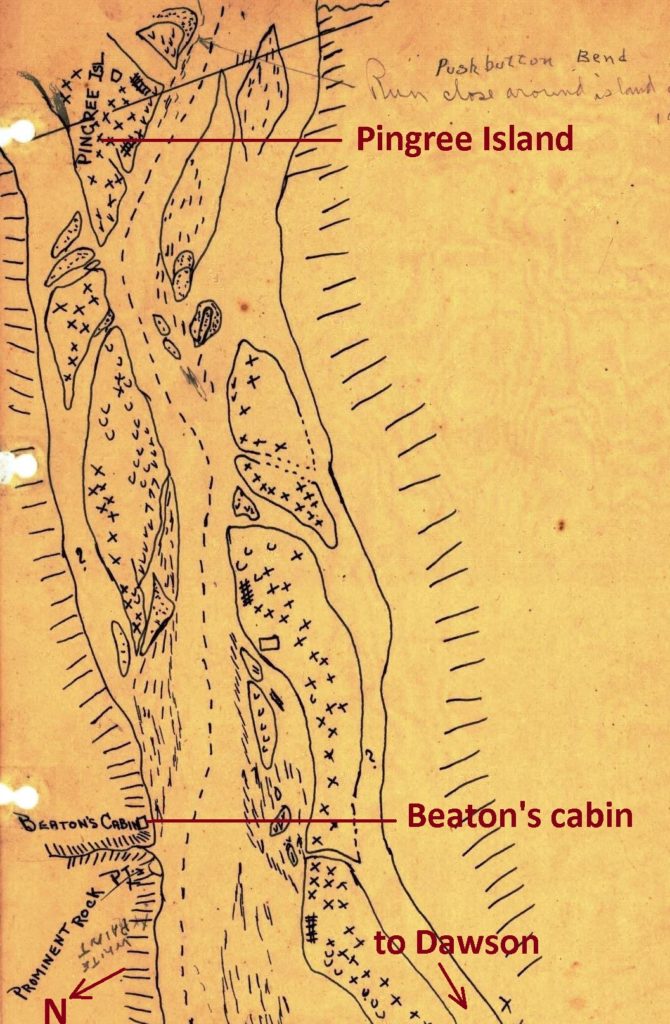

(Library of Congress, Book of running charts of the Yukon and Stewart rivers, 1913-1950)

The river channel chart shows a cabin on Pingree Island, which may be where Beaton first lived to be close to his work. At some point he built a cabin about a mile down (north) from the island on a small knoll overlooking the river, and this is also shown on the channel chart. It is near a prominent rock on the north side of the river that was a landmark for the steamboats.

(Library of Congress, Book of running charts of the Yukon and Stewart rivers, 1913-1950)

In 2017 Ron Chambers and I stopped at the cabin location marked on the chart and climbed up onto the small, steep knoll. The cabin is no longer there, nor any remnants of it, and only a hole that would have been the cellar under it is still visible, along with a few tin cans. The knoll is a very pleasant spot that Beaton may have chosen for its open view of the river and the river traffic, and more sunshine exposure than living at his woodyard in the dark spruce forest.

(Gord Allison photo)

There are other advantages to this location, first and foremost being to get away from ice jams, high water, and bank erosion in the spring that often affect areas along the river. The elevation of the knoll above the river may have provided him a small reprieve of a few degrees of temperature in cold spells during the winter, when the coldest place is at river level. The exposure of the knoll would also have been more subject to welcome breezes during hot periods of the summer and as some relief from insects. Another factor would have been a clear and cold small stream that runs in the little valley on the north side of the cabin site.

(Gord Allison photo)

(Gord Allison photo)

The banks of the hillside at this location are relatively steep and do not allow an easy climb to the cabin, so a road was cut into the hillside on an angle down from the cabin to the river. Beaton likely built this road to haul his building logs up to the cabin site and to provide access afterwards for him and his horses and wagon that he used in his wood business.

(Gord Allison photo)

Sometime by 1914 Finley Beaton had the accident that cost him his right hand. According to Ione Christensen, who later knew him at Minto, he was in a boat hunting ducks and pulled out a loaded shotgun by the barrel and it went off. The ordeal that must have followed for him to get medical attention can only be imagined.

Beaton was afterward called ‘the one-armed woodcutter’, but from photos and a bit of available video the term ‘one-handed’ would appear to be more apt. He had a steel hook attached to the arm and he became known for using it to move wood around with great efficiency. A man who worked on the steamboats for many years, Chuck Beaumont, said that “[Beaton’s hook] was an ideal thing for piling wood…. He had a great woodpile there, and he’d grab the stick with his good hand and put the hook in the other end, and bingo, he was in business”. Beaumont also said that Beaton sold more wood than anybody else.

It is understandable how a hook could be useful for handling lengths of cut wood, but not necessarily so for the axe and saw work involved in getting the wood to that point. Perhaps Beaton had some other sort of attachment he could replace the hook with, or he had employees that took care of that aspect of the work.

The only documentation of Beaton taking a trip out of the Yukon until he left for good was in April 1914, when he returned after being gone for four months. He went to Vancouver, where a newspaper article states that he bought property there, including on Burrard Street where the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver now sits.

Later in 1914 Beaton applied for a homestead (160 acres) near the mouth of Seventeen-Mile Creek, on the southwest side of the river, at an area that had previously been cleared of the timber. The homestead was granted to him in June 1915 and he began living there a month later. The exact location of the homestead has not been determined.

In the summer of 1919 a telephone line, using the telegraph system, was connected to Beaton’s cabin at his wood camp, requiring 1,000 feet of wire. That distance indicates the line must have been put in to his homestead cabin, which was on the same side of the river as the telegraph line, and from where he may have been running his woodcutting operation.

In October 1920 the government enquired about what work Beaton had done toward meeting his homestead requirements. He responded that he had resided continuously on the land since July 1915 and had cleared 10 acres, with five acres under cultivation. He also said that he had built a 16’x24’ house, a 32’x32’ barn, and two storehouses of 16’x16’ each.

In 1922 Beaton sold the homestead to Ralph Blanchard, a fellow woodcutter, and at some point that year relocated to Minto, 40 miles up the river (south). A few years later Blanchard abandoned the homestead and also moved upriver, about 30 miles to the Hell’s Gate area.

Woodcutting in the Minto Area, ca. 1922-1950

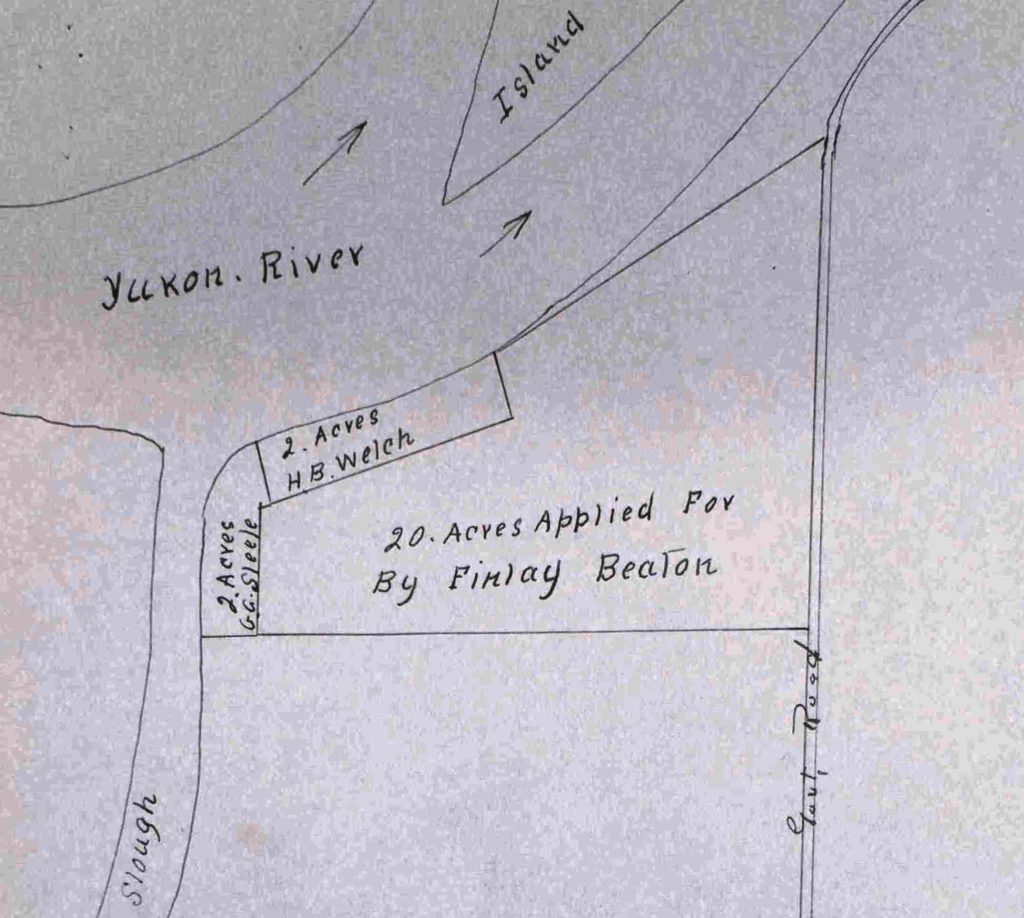

In August 1922 Finley Beaton was living in Minto and applied for a lease of 20 acres of land three miles down the river (north) at the old homestead site of Harris Welch, which had been cancelled the previous year. Perhaps Beaton had moved to Minto because he liked Welch’s spot and was aware that the land had become freed up. He called himself a rancher on his application, perhaps an indication of what he intended to do there.

(Yukon Land Application viewer)

(Yukon Archives, GOV 1665, File 33609)

(Gord Allison photo)

Beaton tried farming at the site in 1923, but he apparently was not willing to give it another try because that October he requested that the government cancel his lease. It did so, but also sent him a letter saying that his yearly rental of $15 had only been paid up to August, so he still owed $1.15 in rent plus interest of 10 cents before his file could be closed.

This prompted Beaton to show his cantankerous side: “I suppose [the government] thinks we raise two crops here. I think [the government is] worse than the gophers and rabbits that destroyed my crop after seeding three sacks oats and one potatoes and paying fifteen dollars for the lease. I got nothing out of it, good investment [eh?]. Now comes this big amount $1.25 on top of all that. I don’t [begrudge?] the final amount – pardon me for taking your time up in reading this note but I had to say something”. This ended his tenure at the old Welch homestead site, but it would not be his last stint there.

In the meantime Beaton carried on his woodcutting activities in the Minto area, primarily upriver (south) from there. Most of it was on islands, which often had the best timber as well as more options for steamboats to land and load up the fuelwood. In 1925, and perhaps other years, he had nephews come from Vancouver to work in the area. He never married and had children of his own, so he apparently put three nephews through school, one becoming a lawyer, one a Vancouver municipal official, and the other a priest.

The best picture I have found of Finley Beaton is in a group photograph from the Yukon Archives taken by Louis Irvine at Minto in 1936. Irvine was employed by Klondike Airways, the company that had the mail contract at the time (although they owned no airplanes). Three Klondike Airways employees are in the photo: Frank Slim of Lake Laberge, the well-known steamboat pilot; Carl Chambers of Champagne (and father of Ron Chambers); and Don Murray of Whitehorse. They were hauling mail and freight with a ‘half-track’ type of truck, with skis on the front tires, and appear to be heading south toward Whitehorse when they stopped at the Minto roadhouse. Joe Horsfall, who had the contract to deliver mail to and from Fort Selkirk and also ran the roadhouse at some point, is in the photo as well. Finley Beaton was living at Minto and likely came over to the roadhouse to visit and was included in the photo.

(Yukon Archives, Louis Irvine fonds, Acc. 82/295, #1902 – photo has been cropped)

Through the 1930s and into the 1940s records show Beaton being issued timber permits for hundreds of cords per year. In 1938 he took out a permit for 500 cords and in 1940, when he was 68 years old, he took out one for 400 cords. It is worth understanding that this was all cut by axe and saw, as portable, one-person chainsaws were not in common use until the 1950s.

Beaton was just one of many woodcutters operating along the river to meet the demand for steamboat wood. In the heyday of the steamboats, 1902 for example, over 16,000 cords were burned that year, of which he might have supplied 500. A cord is a stack of logs typically four feet in length by four feet high and in a row eight feet long, and the cords were usually piled along the top of the riverbank at places where the steamboats could land and load. Beaton’s 500 cords, for example, if piled in one long row would have occupied about three-quarters of a mile of riverbank. Depending on the size of steamboats stopping for his wood, his year of work to cut 500 cords would have been used up in an average of only four round trips of a steamboat between Whitehorse and Dawson.

Beaton’s permits show that his woodyards in the Minto area were upriver (south) from there by up to 14 miles. He would have had to establish a camp near the site for himself and the people he employed and keep it provisioned. Wood was apparently cut all year round, but winter was best for moving the wood to the loading points by sleigh when the ground was frozen, as long as the snow wasn’t abnormally deep. There were undoubtedly some very cold days spent keeping the fire going in a tent frame camp or small cabin and waiting for the weather to break.

(Yukon Archives, Martha Silas fonds, Acc. 87/39, #56 – photo has been cropped)

British Yukon Navigation (White Pass & Yukon Route) was Beaton’s largest customer during these years for steamboat wood, but they were not his only one. In 1941, and perhaps other years, he supplied firewood to Dawson by means of a wood raft due to the shortage of wood in that area for decades following the Klondike gold rush.

Finley Beaton in Retirement and After the Yukon

It appears that Finley Beaton may have eased out of his woodcutting career sometime in the early 1940s. The last record of him cutting wood was in 1942, when he was noted as the only non-First Nation man living at Minto and had sold 300 cords of wood to White Pass.

During the war years in the early 1940s, a number of newspaper articles told of Beaton’s activities at his home in Minto. He apparently had an excellent radio, and when he heard a steamboat approaching he would sit on the riverbank and shout out an update on the war (“they’re giving Hitler hell!”) to the people on board, who had no access to news while on the boat. These articles generally portrayed him as a somewhat eccentric old man living a lonely life at Minto, although one article said he was “… a commanding figure … with great white mustaches” and another called him “the riverbank philosopher”.

In October 1942, a number of newspapers across the country carried a story about a letter Beaton had written to the federal Minister of Finance. He wrote to inform the Minister that he had instructed his banker to purchase $5,000 in Victory Bonds to assist in the war effort, which was in addition to $5,000 he had already loaned on each of the two previous Bond campaigns.

The fall of 1942 saw the passing of Beaton’s neighbor, Ernest Thoms, at the cabin three miles down the river from Minto. Beaton bought or was given the cabin after Thoms’ passing and moved in there, and became the person most associated with this site because he was the last to live there.

(Gord Allison photo)

It appears that Beaton spent the next several years at ‘the Beaton place’ until he left the Yukon. Ione Christensen said she and her parents would occasionally visit him there, and he would always give some of his home-made dandelion wine to her father, RCMP Cpl. G.I. Cameron.

Finley Beaton left the Yukon in about 1950 and first went to Kitimat to live with family. From there he moved on a few years later to Abbotsford, where he lived with Michael Beaton, one of his nephews that had come to see him in the Yukon.

Beaton was said to have owned several houses in Vancouver that he had bought unseen. What happened with these and other investments he may have had from his decades of hard work handling cordwood is not known. His obituary only stated that he was survived by four nephews in BC, even though he came from a large family in Nova Scotia. Beaton died of bladder cancer in the Matsqui hospital on May 16, 1960 at the age of 88. He was buried in the Hazelwood Cemetery there and his headstone inscription reads “In loving memory of our dear uncle”.

Finley Beaton was a very successful woodcutter for decades in the Yukon despite (or perhaps because of) losing a hand. He was another ‘character of the country’ and was generous with the fruits of his labors. The mark he left here is fading from the landscape and from people’s memories as time goes on, but recording his story can help to preserve it.

Link to related article: Finding Welch’s Fields

Outstanding Gord!!

Thanks for reading it and for the comment, Boyd, I always appreciate hearing from you.

Tough old buggers in those days. We all complain about the hard work of cutting a couple cords with chainsaw and truck.

Yes, they were tough and determined people to do what they did. I’m pretty sure if you were alive then, you would have been one of them.

Wondering Gord what WP was paying for a cord of wood stacked on the river bank- say during the 30’s?

I don’t have a lot of information, Boyd, but I’ve seen that in 1902 they were getting around $5-6 per cord. Years later Finley Beaton got as high as $12 a cord, but in 1941 it was back down to $8, so not a big increase in 40 years. White Pass probably got a volume discount on the wood they bought, and I don’t know what guys like Beaton would have gotten for wood they rafted to Dawson and sold publicly, but probably more – from what I’ve read that wood was snapped right up because of the lack of it around Dawson.

Just curious as Finley Beaton would be amongst the hardest working men in the country and he appears to have been very successful with the assets he obtained. However, in the days when men were working for $2/day he was very likely putting up 2 cords per day (with a horse or team) so the trade was very lucrative with his hard work.

A 500-cord year at $8/cord would be a gross income of $4,000. I don’t know if he had other income as well. This would be minus his living expenses and any hired help he might have had. He appeared to earn enough to invest in houses and property in Vancouver, whatever the prices were in his day. That information about him comes from a few newspaper articles, which you have to talk with a small grain of salt, and some first-hand knowledge.

That same shotgun/duck hunting accident happened when I was a kid in Eastern Ontario. Single shot ( Loaded) 12 gauge with a hammer- the hammer catches on the gun whale of the boat while lifting the gun by the end of the barrel severing the persons hand from the forearm. My brother and I got schooled from my Dad about the dangers of performing this act.

Thank you so much, this was so interesting, and what a lot of research!