Minto-Fort Selkirk-Pelly Crossing Area Meadows

(Yukon Archives, Van Bibber family fonds, Acc. 79/2, #30 – photo has been cropped)

Introduction

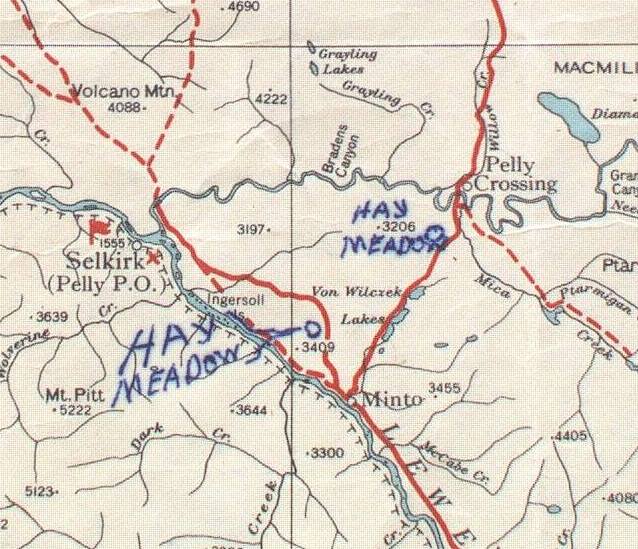

The story of the Bradley family of the Pelly River Ranch harvesting wild hay from the Nine-Mile meadow was told in Part 1 of this two-part article. Part 2 looks at earlier hay cutting in this same part of the Yukon, where a cluster of meadows is an example of the Yukon’s little-known hay meadow cutting history. This area is in and around the Minto-Fort Selkirk-Pelly Crossing triangle of the central Yukon, and this history involves people who played a role in Yukon homesteading, farming, outfitting, and related ventures.

There are at least ten meadows in this triangle area that were known to be harvested for hay. All except one of them are now hidden in the bush and seldom seen by anybody, and show little evidence of the work that once occurred there. Nine of these are the focus of this Part 2 article, the other one being the Nine-Mile meadow (first called the ‘central Morrison meadow’) that was the subject of Part 1. There is some overlap of information between these two parts for geographical and historical context. (see link to Part 1 at end)

(Google Earth)

Yukon Meadow Haying

In September 1898 while Dawson City and the Klondike region were swelling with gold rush activities, the Dawson newspaper Klondike Nugget reported that “hay has been brought in this summer for hundreds of miles and has proved a profitable investment to the bringers”. The “supply was not nearly equal to the demand” to feed the amount of livestock that was coming into the Klondike for food and work purposes. Once it was proven that horses could survive the Yukon winters and, in the words of William Ogilvie, “… that they [can] live only on the coarse grasses of the country”, the transition from dogs to horses as the main work animal of the Yukon was underway.

The following year in October 1899, the newspaper described a striking scene, that “Dawson’s hay wagons – [in the form of] rafts – are just in from the hayfields and for half a mile are securely anchored to the beach”. These hayfields were natural meadows, where “wild grass in favorable ground grows five feet high”, according to the 1898 article. This may be an exaggeration in most cases, but it is evident that Yukon meadows were a necessary resource to sustain the influx of horses, which numbered over a thousand in the Klondike during the winter of 1899-1900.

Like gold, a meadow is where you find it, and the 1899 newspaper article reported that “the bulk of the hay … is … cut on the sandy banks of the Yukon [River], above [Fort] Selkirk”. This is 170 miles and more up the river (south) from Dawson, but if the newspaper statement is accurate, it seems probable that some of this hay came from meadows covered in this article.

Within a couple of years the harvesting of natural meadows diminished, becoming replaced by hay importation and hay grown on newly established farms in the Klondike area. However, meadow cutting continued on a smaller local scale for decades afterwards, primarily by livestock owners both for their own use and some to sell.

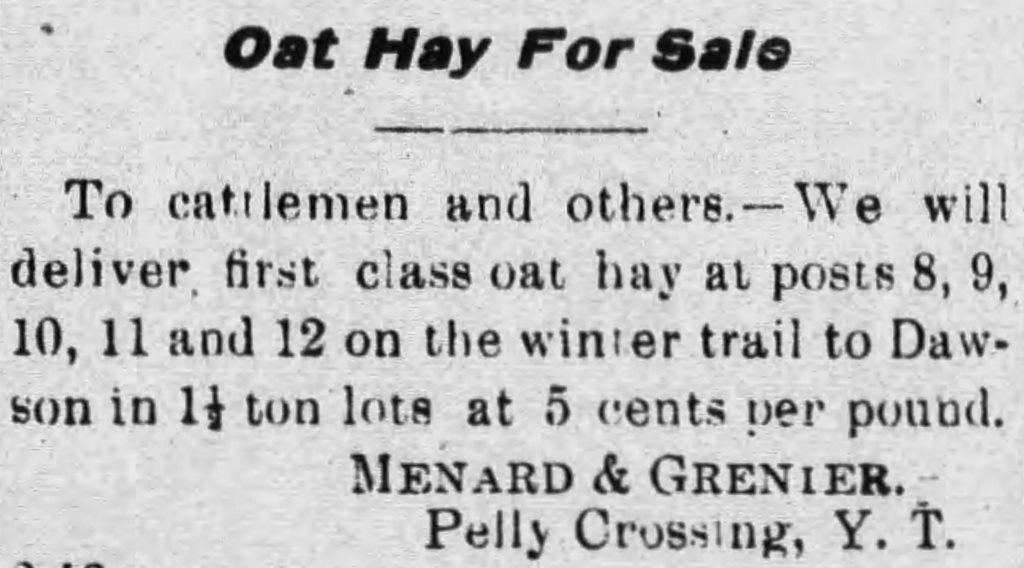

A market for some local hay was provided by horse-drawn stage lines that operated on the Yukon River winter trail (1898-1902) and then the Dawson-Whitehorse Overland Trail (1902-early 1920s), both of which went through the Minto-Fort Selkirk-Pelly Crossing area. The hay was stocked at the roadhouses along the route, where the horses were fed and rested in stables after completing a section of the trail. This market disappeared in the 1920s when the use of horses for transport began to be replaced by tracked machines and trucks on the Overland Trail and the new road from Minto to Mayo and Dawson. (see link to related Overland Trail article at end)

(Whitehorse Daily Evening Star, 20 March 1905)

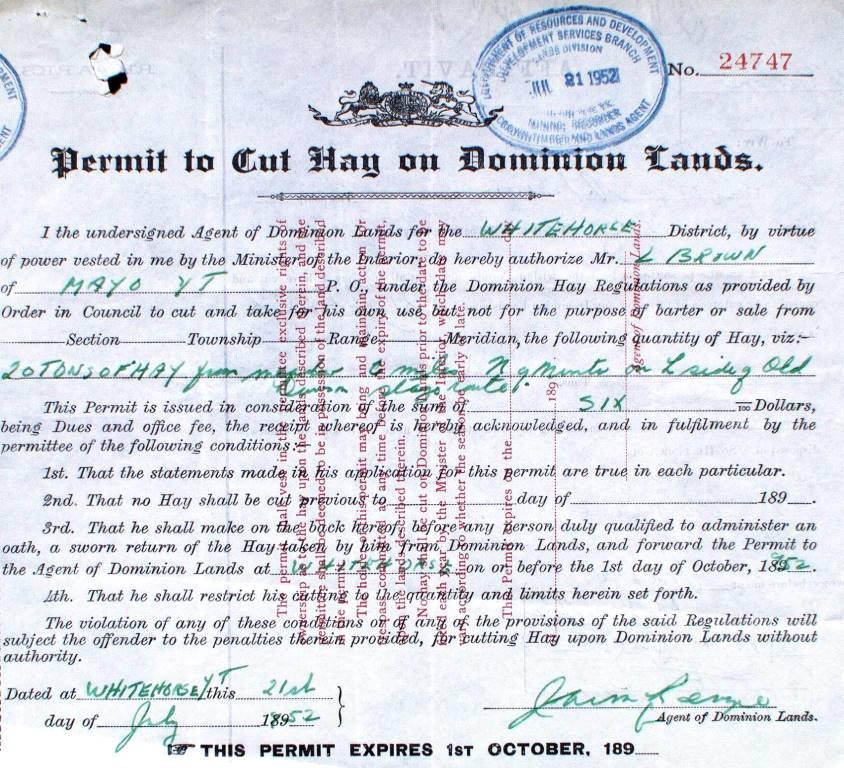

It wasn’t long after meadow haying started in the late 1890s that the federal government began to issue permits and leases, along with levying fees, for the right to do it. The archival records of this activity go until 1957, but some known cutting of meadows is not contained in them, indicating there was more of it carried out than what the records show. The Bradleys cut hay at the Nine-Mile meadow into the early 1970s, and there may also have been others who harvested Yukon meadow hay until then or even longer as well.

Some other sources of information relating to hay meadow cutting include a few written accounts, newspaper articles, and photographs, as well as the knowledge and memories of people who were involved in these endeavors or witnessed them. These sources along with the archival records form a patchwork of information that paint a picture of this enterprise on the Yukon landscape.

The Swinehart Meadow (ca. 1899-1914)

In March 1898 William Swinehart along with his son Guy and two other men, all from Wisconsin, came over the Chilkoot Pass with farming equipment and four horses. They were bound for Fort Selkirk, where Swinehart’s friend Frank Bach of Juneau had staked land for agricultural purposes. They arrived there in mid-June and set to work establishing the Swinehart Farm two miles in the bush to the west of the settlement.

(Yukon Government Historic Sites photo)

A Dawson newspaper The Yukon Sun reported in early 1903 that William Swinehart had “a large tract of meadow land that produces as good a class of hay as can be purchased on the outside [of the Yukon]”. This meadow was just to the west of the farm site and it is reasonable to think that cutting hay from it may have been one of the Swineharts’ first agricultural endeavors after arriving at the site. It would have provided winter feed for their horses and perhaps some surplus for income while they were clearing land and building the farm nearby. The following year, after hay cutting regulations were put in place, Swinehart took out his first permit on May 2, 1899 for 20 tons of hay.

(GeoYukon)

(Heather & David Ingrams Collection)

The 1903 newspaper article said that Swinehart was growing oat hay, which was oats that were seeded in the hay meadow. Later that year the Dawson-Whitehorse Overland Trail was built just a few miles east of the farm, opening up a ready market for sale of the hay to the White Pass & Yukon Route for the horses on its stage line.

In July 1903 Swinehart received delivery of a hay mower and hay rake by steamboat at Fort Selkirk. These horse-drawn implements would have greatly aided the harvesting over the previous scythe and pitchfork tools they had been using.

(Coltrin family collection)

(Coltrin family collection)

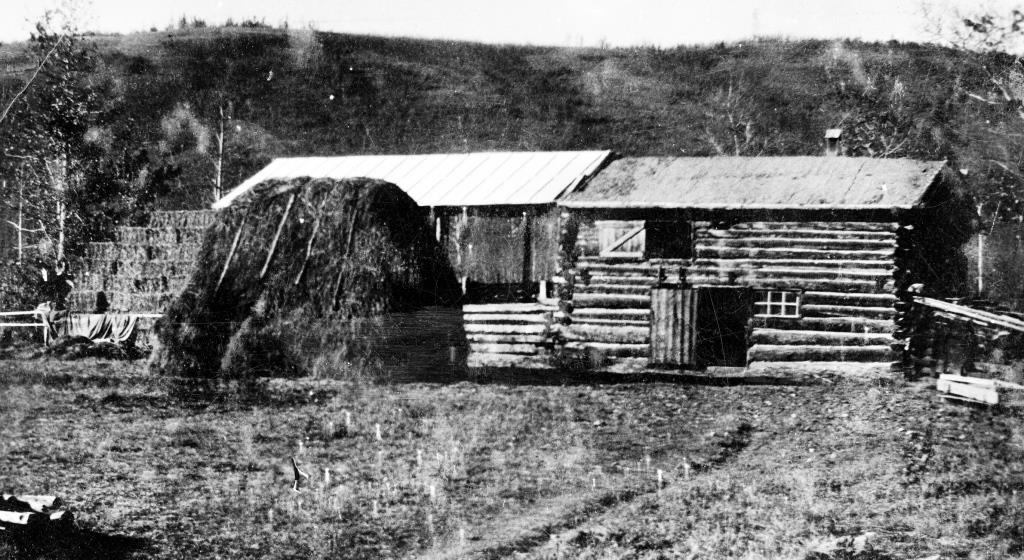

The Swinehart Farm came to a fairly sudden end in July 1914 when William Swinehart died while working in his field. There is no record of anything happening with the farm after that and it was left to be reclaimed by the bush. The hay meadow is still there, though smaller now as vegetation on the edges slowly tries to overtake it. (see link to related Swinehart Farm article at end)

Atkinson’s Meadow (1903 – ?)

William Atkinson from Ontario took out a homestead in Alberta and was developing it until leaving to join the Klondike gold rush in 1897, coming to the Yukon by the Edmonton Trail. His gold mining plans evidently didn’t work out, but he stayed and began establishing a homestead on the east bank of the Yukon River about 14 river miles upriver (south) from Fort Selkirk.

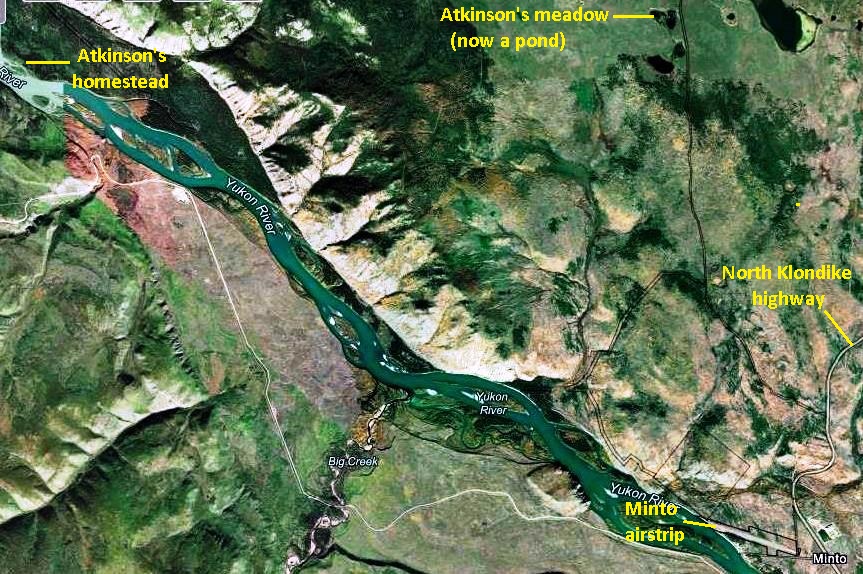

In 1903 Atkinson applied to purchase the “central Morrison meadow”, as well as a 40-acre one he called the “Atkinson meadow”, presumably meaning that he had already been cutting hay from it. The latter meadow is about seven miles in a direct line east of his homestead and six miles north of Minto.

(Yukon LandsViewer)

(National Air Photo Library, A13628, #7)

William Atkinson resided at his homestead area for several more years, but it is not known how much harvesting of hay he may have done at this meadow. Transporting the hay from this location would have presented some challenges, particularly before the second route of the Overland Trail ran past it.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, and perhaps later, Atkinson’s meadow was cut for hay by the well-known Mayo-based big game outfitter Louis Brown. This meadow was part of what became known as the “Louis Brown meadows”, and will be looked at in a later section of this article.

Welch’s Meadows (1903 – 1916)

Harris Welch was a school teacher in California when he left to join the Klondike gold rush in 1898. By the time he arrived the mining creeks were all staked up, and so the following year he established himself at a location on the east side of the Yukon River three miles down the river (north) of Minto. Here he built the Hay Cache roadhouse that he operated for a few years and also began a fairly ambitious farming enterprise, for which he acquired a number of parcels of land.

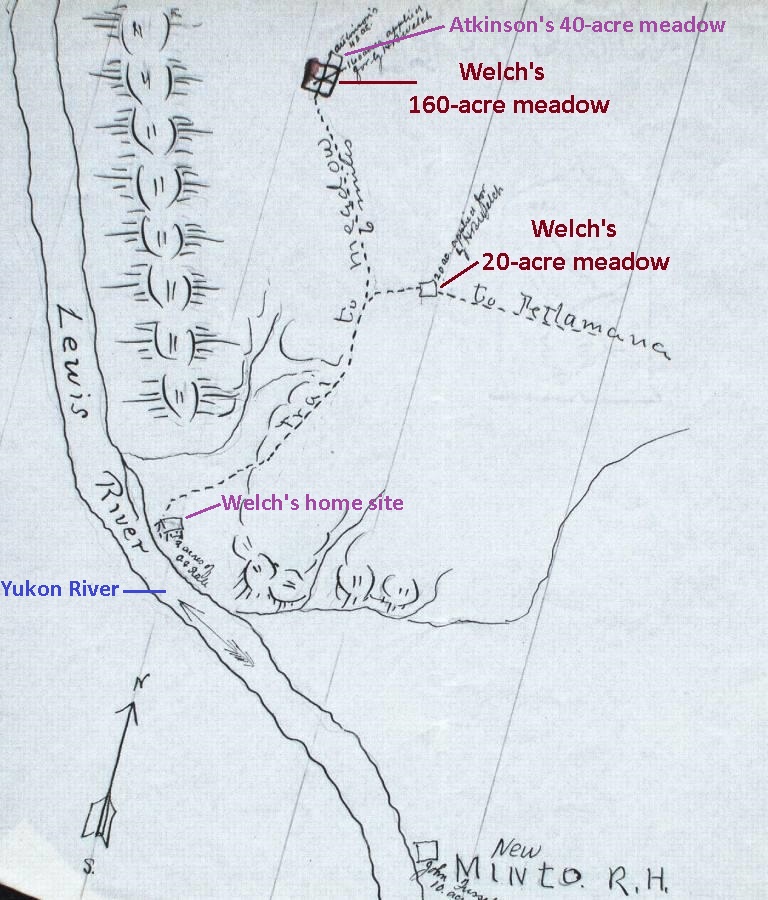

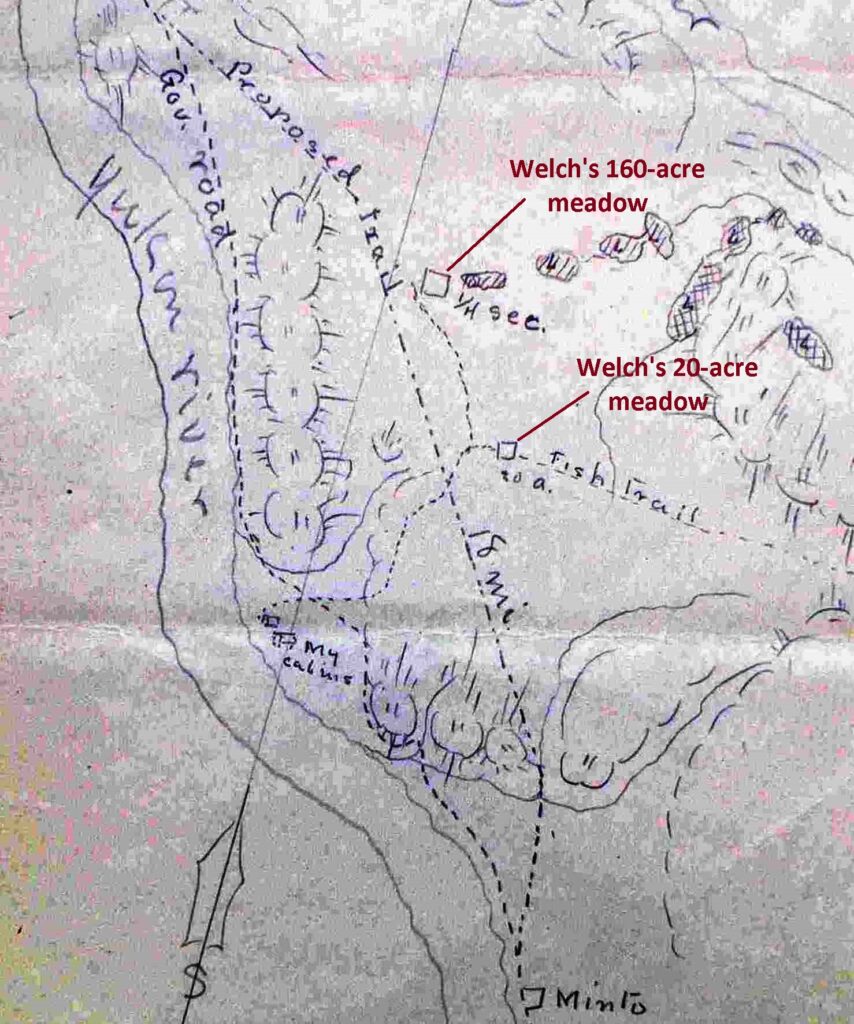

Two of these parcels were meadow areas that he applied for in the spring of 1903, one for 20 acres three miles north of Minto and the other for 160 acres about 5½ miles north of Minto and adjoining Atkinson’s 40-acre meadow. The 160-acre parcel was for a homestead and in actuality only about half of it was meadowed, with the rest covered in small forest growth.

(Yukon Archives GOV 1634, File 7078 and GOV 1634, file 7799)

In the fall of 1902 the Dawson-Whitehorse Overland Trail had been built along the Yukon River and past Harris Welch’s home site, but it was a section of road that was difficult to maintain. The following June, around the same time he was applying for his meadows, he wrote the government to suggest a new 20-mile route inland away from the river at Minto to avoid this bad section. Sometime later, this second routing of the Overland Trail was built more or less as he proposed and passed by his and Atkinson’s meadows, which would have made access much easier for both of them to cut and haul out their hay.

(Yukon Archives GOV 1630, file 4738)

Welch completed his payments on the 20-acre and 160-acre parcels in two and three years, respectively, indicating that he was using them. While he became known mainly for growing potatoes, he would have cut hay for his own horses and may also have sold some. Welch’s 160-acre meadow area, together with the adjoining Atkinson 40-acre meadow, later became known as the ‘Louis Brown meadow’, to be discussed.

Aerial imagery shows that at some point Welch (or possibly somebody later) squared off his 20-acre parcel like a field, indicating that it may have been tilled and grew crops other than, or in addition to, wild hay. Recent imagery shows that more than 100 years after Harris Welch left the Yukon, much of his meadow has grown back in, and in 2023 it was only about 4½ acres in size.

(National Air Photo Library, A13628, #7)

(GeoYukon)

(Gord Allison photo)

In 1916 Harris Welch left behind all the work he had put into his homesteading enterprise when he departed the Yukon for Washington state. The 20-acre meadow and other areas of the landscape north of Minto still show the imprint of his endeavors. (see link to related Welch article at end)

Hayrack Lake Meadow (1911 – 1922)

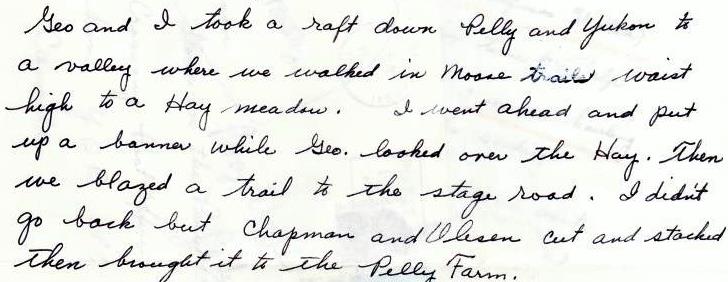

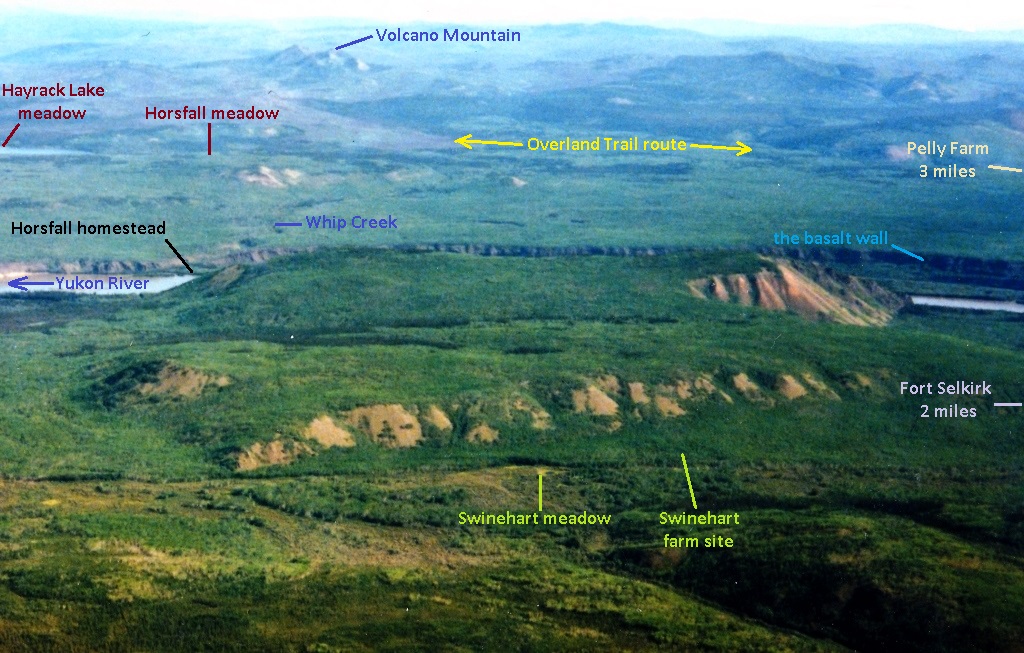

George Grenier came from Quebec to the Yukon in 1898, presumably with dreams of gold like everyone else, but instead became one of the founders of the Pelly Farm (now known as Pelly River Ranch). A few years later, probably in 1910, he and his teenaged stepson Percy Wright made a trip into the bush about 8½ miles northwest of the farm to locate and stake a claim to a meadow for haying purposes. They took a much longer route to get there, however, going first by raft down the Pelly River into the Yukon River and past Fort Selkirk about five miles, a water trip of about 11 miles. At the mouth of a small stream called Whip Creek on the north side of the river, where a homestead would soon be established by Joseph and Julia Horsfall, Grenier and Wright left their raft and began walking inland.

(Google Earth)

From the river Grenier and Wright walked three miles northeast up the creek valley on the ‘Selkirk Cut-off’, a sleigh road that connected Fort Selkirk with the Dawson-Whitehorse Overland Trail that bypassed the community by a few miles. They then turned northwest and walked another five miles in “moose trails waist high” to a meadow surrounding a small lake that is locally known as Hayrack Lake. In the meadow that surrounded the lake, they put up a “banner”, presumably some sort of marker akin to staking a mineral claim. Upon completion of their mission, they blazed a trail eastward for 1½ miles through the bush to the Overland Trail and then walked along it the 8½ miles back to Pelly Farm.

(Lew Johnson collection)

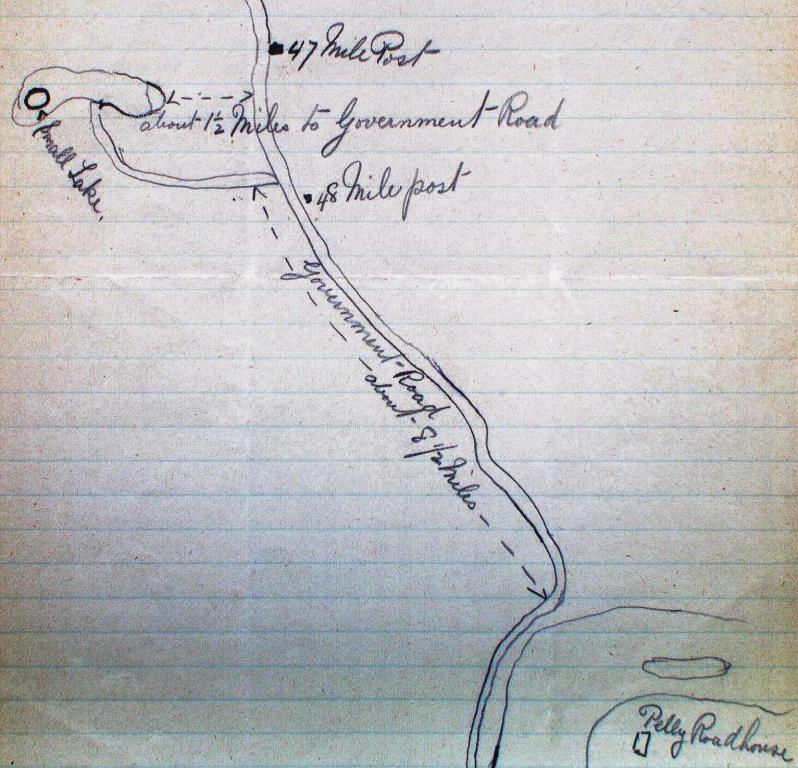

In June 1911 Grenier submitted his application for a 25-acre lease at this meadow, described as between Overland Trail mileposts 47 and 48 (as measured from the Stewart River) and 1½ miles to the west of the Trail. He said he had sold the farm the previous year to Frank Chapman and Peter Oleson, so it is not clear what his needs or intentions for this meadow were.

(Yukon Archives, GOV 1649, file 27178)

(National Air Photo Library, A17344, #61)

George Grenier cut hay from the meadow in 1911 and 1912, but by then he was living at other locations such as Yukon Crossing and Fort Selkirk. In March 1914 he wrote to the government that he no longer wanted the hay lease, and in July Chapman and Oleson, the new owners of the farm, applied to take it over.

The notes made by Grenier’s stepson Percy Wright say that Chapman and Oleson cut and stacked hay at the meadow and then brought it to the farm, which was likely in winter in a wagon on a sleigh pulled by horses. Chapman and Oleson paid the yearly rental fee until March 1923, when they informed the government that they wanted to cancel the lease. It would appear that for 10 years or more they harvested the hay from Hayrack Lake.

It is uncertain where the name Hayrack Lake came from, but that is what it was always known as by the Bradleys, who have owned the Pelly Farm since 1954. In the 1990s Hugh Bradley and his nephew and co-owner Dale Bradley went to the lake, where Hugh pointed out distinct rectangular patches of thick vegetation growth indicating where hay had once been stacked. Hugh also said that in a previous visit he had seen some old haying equipment left in the bush there.

Horsfall Lakes Meadow (1915 – 1922)

Joseph Horsfall was from England and in the 1890s ended up in Fort Yukon, Alaska, where he married a woman from the area, Julia Kirkby Sim. In about 1902 they and their two daughters moved to the Yukon and engaged in a trapping life on the Pelly and MacMillan Rivers before settling at Fort Selkirk a few years later.

Sometime after 1910, by then with a larger family, the Horsfalls began establishing a homestead on the Yukon River five miles downriver (west) from Fort Selkirk and on the opposite side. It was at the mouth of Whip Creek, whose valley provided one of the few breaks in the large volcanic basalt wall that abuts the river for many miles in that area. There they built a house and farm buildings and cleared and cultivated land for crops.

(Yukon LandsViewer)

(Gord Allison photo)

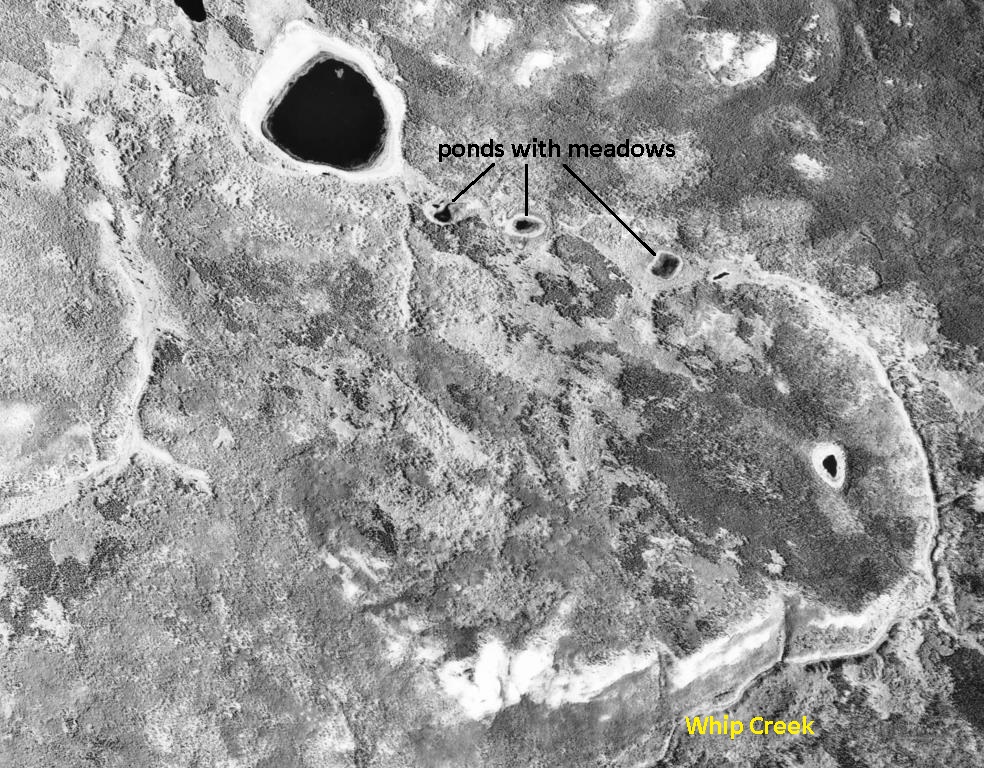

In April 1915 Joseph Horsfall applied for 25 acres of “hay land” north of the homestead by the same access used a few years before by George Grenier and Percy Wright to the nearby Hayrack Lake. This route was three miles along the valley of Whip Creek, also the route of the ‘Selkirk Cut-off’ that linked the community with the Overland Trail, and then a mile to the west. Horsfall provided a sketch with his application of the 25 acres encompassing two ponds that had hay growing around their margins. His arrangement was not specified as a permit or lease like others, but an annual rental of 50 cents per acre “to occupy the land”.

(Library & Archives Canada, RG85 vol. 1521, file 2244)

(National Air Photo Library, A17344, #59)

(Gord Allison photo)

In December 1922, after potentially eight years of haying these meadows, Joseph Horsfall wrote a letter requesting cancellation of his arrangement to use this land. His reason was that by then he had more land under cultivation on his homestead and would be able to grow enough livestock feed there for his needs.

Horsfall’s hay land application did not call the lakes and meadows area by any name nor have I seen a name in other documentation. However, journal notes made by J.C. Wilkinson, who along with his wife and grown children owned and operated the Pelly Farm from 1940 to 1954, referred to the area as the (misspelled) “Horsefall Lakes”. The Horsfalls were long gone from their homestead by 1940, but the Wilkinsons, who used the lakes for hunting ducks and trapping muskrats, would have known the Horsfalls and their history in the area.

Horsfall Lakes was also the name used by Hugh Bradley, one of the owners of the Pelly Farm/Pelly River Ranch after the Wilkinsons. It appears that this was the local name of the area for a few decades, but it evidently fell by the wayside over the years. I am resurrecting it for the purpose of this article.

The Horsfall homestead and meadow locations are contained in a 1988 photo from the air that also includes the Swinehart and Hayrack Lake meadows. This photo shows the geographical context of these three meadows in relation to natural and human features.

(Gord Allison photo)

Van Bibbers’ Meadow (ca. 1930s – ?)

In late July 1988 I spent a day walking in the bush near Pelly Crossing with Dan Van Bibber, an energetic 75-year old who was the fourth child and second son in the large family produced by Ira and Eliza Van Bibber. Ira was a West Virginian who came to the Yukon in 1898, married Eliza Jackson from the Fort Selkirk area, and together they established a family home at Mica Creek, near Pelly Crossing. In one of our conversations, Dan told me about cutting hay as a young man from a meadow about five miles south of Pelly Crossing, and that in the springtime they would burn around its edges to keep the willows from encroaching. This meadow is shown in the photo at the beginning of this article.

(National Air Photo Library, A13628, #3)

A reference to the Van Bibbers’ use of this meadow appears in Pack Horse Tracks, geologist Hugh Bostock’s memoir of his work in the Yukon. In mid-August 1933 he was walking south from Pelly Crossing along the Minto-Mayo road (the precursor to the North Klondike Highway in that area) when he encountered 20-year old Dan Van Bibber and some of his younger brothers harvesting hay in the meadow. They were cutting it with a scythe, and according to Bostock it was for their “dog stables”, meaning bedding for the dogs at their homestead near Pelly Crossing. The Van Bibber family photo of their hay cutting activity in the meadow includes a horse pulling the hay wagon, suggesting that some of the hay may have been for horse feed as well.

When Dan Van Bibber was telling me about the meadow, we also talked about how it had become a small lake many years previously. After a forest fire burned through the area in 1969, the water-holding capacity of the surrounding vegetation was greatly reduced and allowed local drainage to fill the meadow area.

(National Air Photo Library, A37495, #61)

(Gord Allison photo)

I have no information about how long the Van Bibbers harvested hay from this meadow, but they appear to have stopped by at least the late 1940s. This is because the outfitter Louis Brown applied in 1950 to cut hay there, and I have heard this meadow also referred to as the ‘Louis Brown meadow’.

Louis Brown Meadows (formerly Atkinson’s, Welch’s, and Van Bibbers’ meadows) – 1950s-1960s

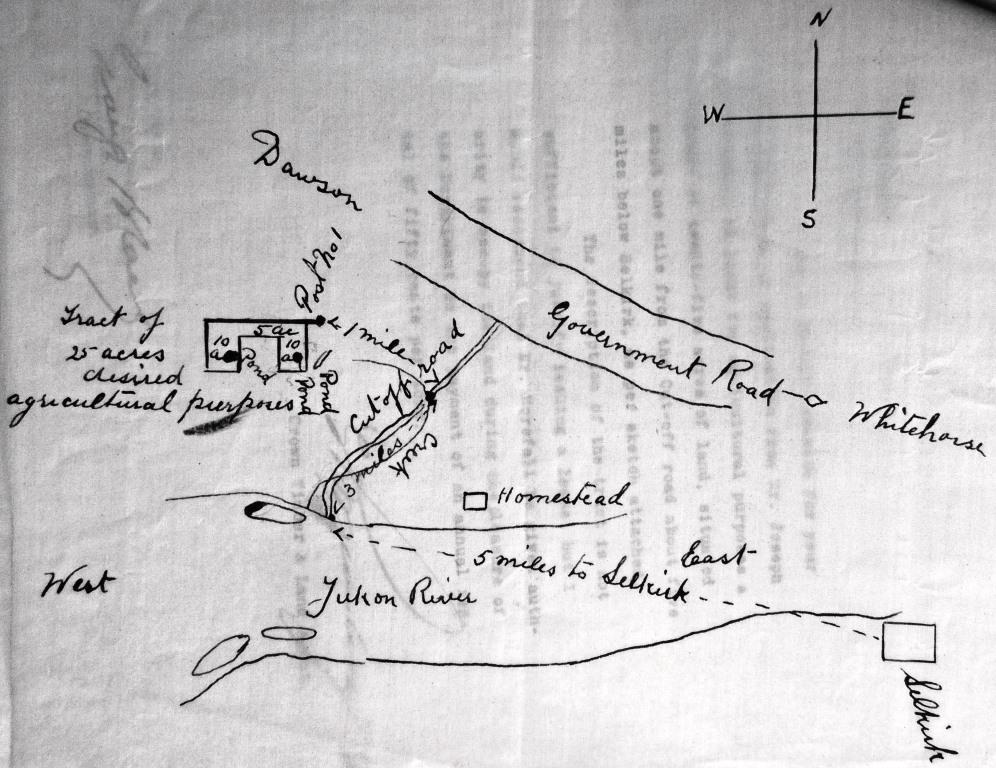

Louis Brown came to the Yukon from Alberta in the 1930s and became a trapper, prospector, big game hunting outfitter, and rancher based in the Mayo area. In 1950 he applied for cutting permits for 20 tons of hay from each of two meadow locations in the Minto-Pelly Crossing area.

One application was for the series of meadows used by William Atkinson and Harris Welch in the early 1900s north of Minto along the second routing of the Overland Trail or the “Old Dawson Stage Route”, as Brown called it on his application. It became more commonly known as the Pelly Farm Road after that, and now is referred to as the Old Pelly Farm Road or Old Pelly River Road. This is not to be confused with the modern Pelly Ranch Road that begins at Pelly Crossing.

(Yukon Archives, GOV 1663, file 977)

Brown’s other application on a similar form was for the meadow previously described as the Van Bibber meadow beside the highway about five miles south of Pelly Crossing. He also submitted a portion of a map that showed both of the meadow locations he applied for.

(Yukon Archives, GOV 1663, file 977)

Brown’s cutting activities on the Atkinson and Welch meadows, and perhaps also the Van Bibber meadow, carried on into the 1960s and possibly later. In occasional travels along what is now the Old Pelly Farm Road with the Bradleys of the Pelly River Ranch, we would sometimes see Brown with his small tractor and mower cutting his hay and the wall tent he had set up there for his living quarters. These meadows that Brown cut eventually became ponds from water drainage into them following forest fires in the area.

The Morrison Meadows (1899-?)

This hay meadows article had its origin when I came across a file in Library & Archives Canada in Ottawa about an application made in 1899 by Alex Morrison, a Dawson miner, to lease three meadows in the Hells Gate area of the Yukon River near Fort Selkirk. These meadows may have provided much of the hay described as being brought to Dawson on the rafts that were parked on the waterfront there. The details of the use of these meadows by Morrison and later by area homesteader William Atkinson are likely now lost to history.

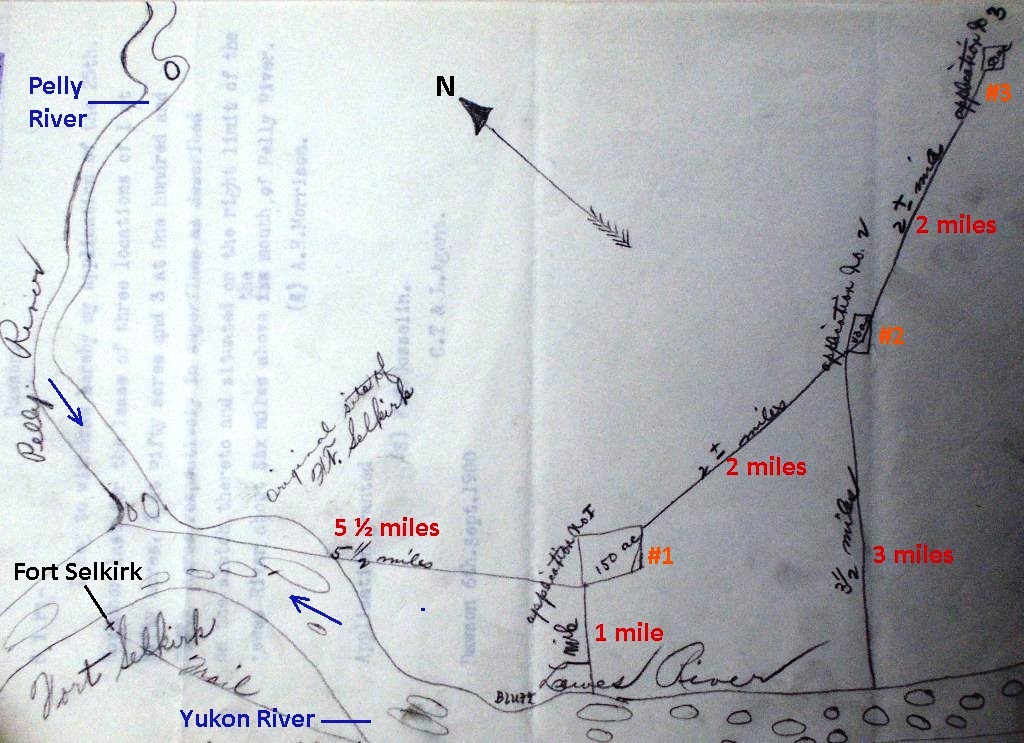

Morrison’s application, which was introduced in Part 1 of this article, included a sketch map with very accurate plotting of the meadows and the distances involved. The ability to measure distances in this area of relatively thick bush with the tools, methods, and base mapping that would have been available at the time is noteworthy.

(Library & Archives Canada, RG85 Vol. 1519, File 1582)

(Google Earth)

When Morrison’s sketch was compared with modern air imagery, it was evident that his central meadow (#2) was the Nine-Mile meadow harvested more than 60 years later by the Bradleys of the Pelly River Ranch. This connection generated the story in Part 1 about this meadow being one of the earliest in the Yukon to be cut for hay and also one of the last. That led to this Part 2 about the hay cutting history of other meadows in the area.

(Gord Allison photo)

Ending

The cutting of wild hay from Yukon meadows began in the late 1890s and went on for over seven decades, but it has not been well reported or recorded. After an initial flurry of commercial activity following the Klondike gold rush, haying became mainly a local endeavor by individuals or families trying to make a living from the land. Their cutting of meadows was on a small scale and in most cases not very visible, so obtaining authorization to do it and paying fees for it may not have been pursued by some who engaged in it. Therefore the record of many of these activities has likely now been lost to time, but the records that do exist along with the knowledge, memories, and photos of some of them can offer a sense of the Yukon’s meadow haying history.

(Gord Allison photo)

Link to Part 1 – The Nine-Mile Meadow

Link to related article – The Overland Trail

Link to related article – Swinehart Farm

Link to related article – Finding Welch’s Fields

A fascinating read, Gord, thank you. So many thoughts popped into my head such as the government agricultural paper and fee requirements for a pioneer economy, especially hay where horses were the primary engines of transport. The “Tetlaman Trail” indicated on H. Welch sketch was the last leg of the provisioning trail used by HBC Fort Selkirk (1848-52) back to the Mackenzie River. Flora and ground changes from HBC Robert Campbell and 1988 Dan Van Bibber and your current observations of the meadows raise very interesting climate questions.

Thank you for your observations as always, Lew. The old trail between Minto and Tatlmain Lake is shown in Ruth Gotthardt’s Tatl’á Män booklet, but I hadn’t thought of it also being used by the Hudson’s Bay Company. It makes sense once I had a reminder look at your “Journal of Occurrences” paper of the Fort Selkirk area and see the trail on your map there. A very interesting part of the Yukon from many perspectives.

Another enjoyable read Gord, great details. Re Harris Welch, never underestimate the value of potatoes from either side of the equation. Then there is permitting; where would we be without permits for everything? Thanks again.

Rob, in most archives land files I’ve looked at where permits, leases, homesteads, etc. were involved, I would guess at least half the pages are administrative, primarily to do with the government trying to collect fees and payments. You have to thumb through all these pages in trying to find the ‘real’ and interesting history in the files. Thanks, I always appreciate your comments.

Hi Gord, I really enjoyed your blog post. I’m a graduate student pursuing a PhD in paleolimnology and I’ve reconstructed the past ~200 year history of the lake that was once Van Bibber meadow (not knowing it was a meadow before coming across this post!).

I am trying to fill in some knowledge gaps here though and am hoping you might be able to help – although this might be a long shot. I do hope my questions aren’t too picky or forward!

Firstly, do you have any idea when hay harvesting began at Van Bibber meadow? Do you know if they used any fertilizer (I’m thinking possibly horse manure?) on the land? I’m also keenly interested in any documents or information you could provide on the exact timing and mechanism of the meadow fill with water to become a lake. You mentioned it could be due to forest fires (and that this has occurred to several meadows in Yukon). I find this particularly interesting!

Thanks for taking the time to read this and hopefully hear from you soon.