Bill Watson’s Letter

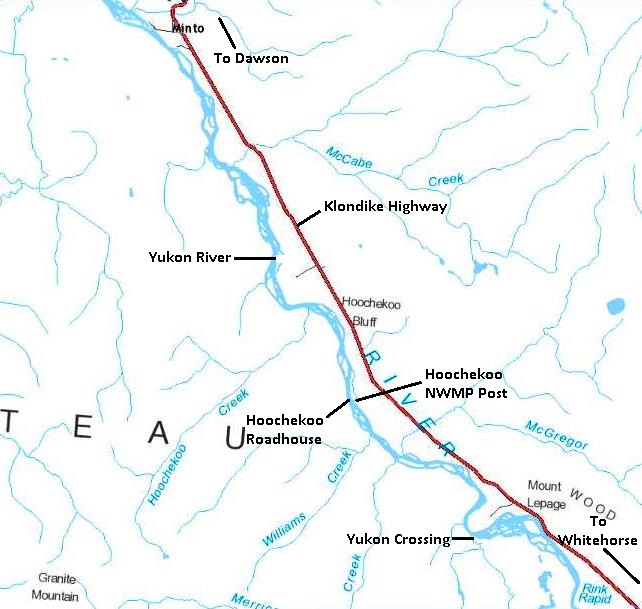

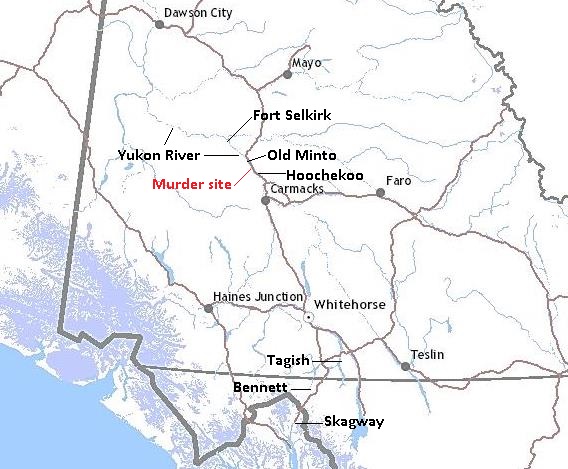

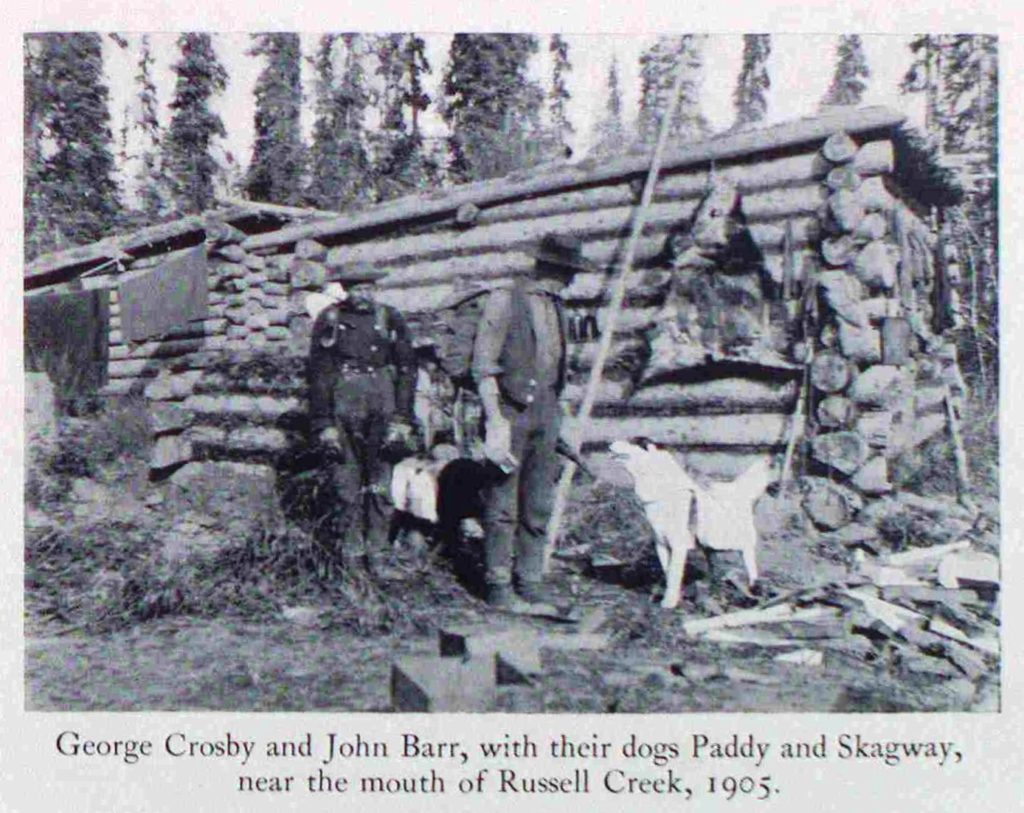

In early 2016 I came across a letter in the Yukon Archives that was written in 1974 by a Bill Watson of Bellingham, Washington to Dick and Hugh Bradley at the Pelly River Ranch, located 10 river kilometers from Fort Selkirk. Bill, then aged 82, had read a magazine article about the ranch, and it was apparent that a sense of nostalgia prompted him to write to the Bradleys.

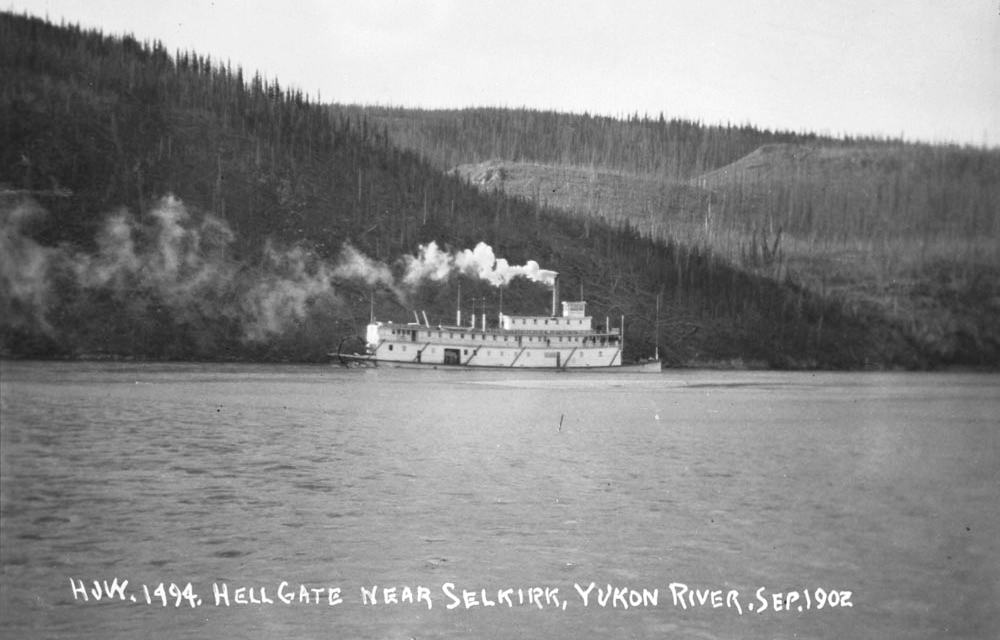

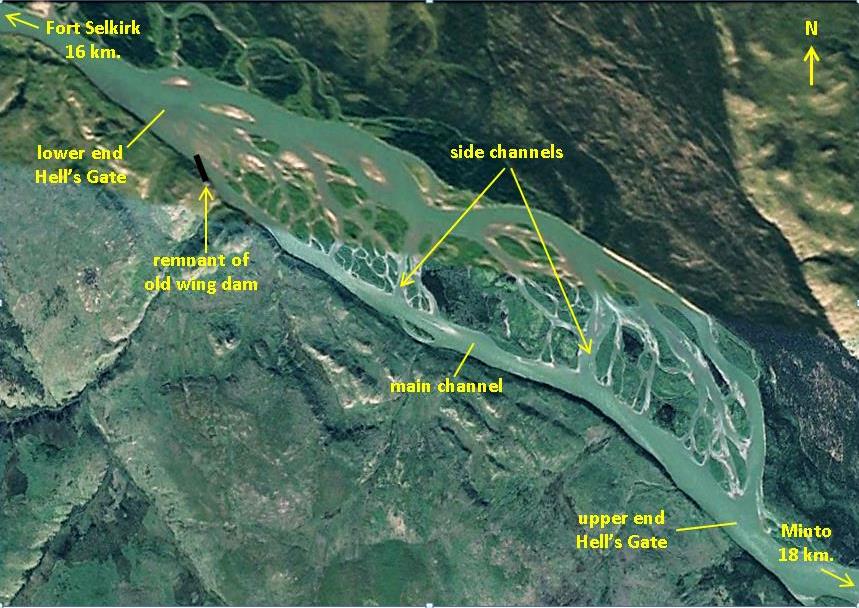

The letter explained that in the fall of 1910, when he was 18 years old, Bill was sent to Fort Selkirk to be the telegraph operator there for a year. It also said that Bill’s family had come north with the Klondike gold rush and eventually settled in Whitehorse, where he grew up.

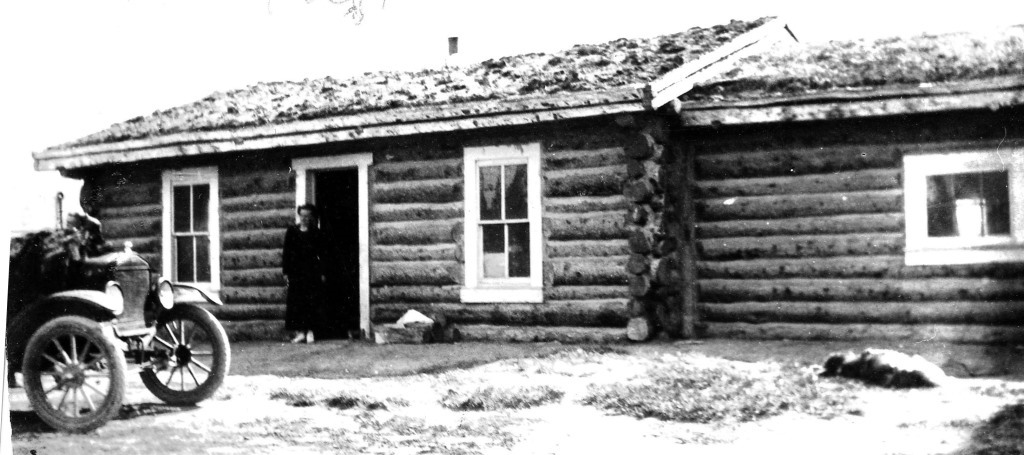

(Watson family collection)

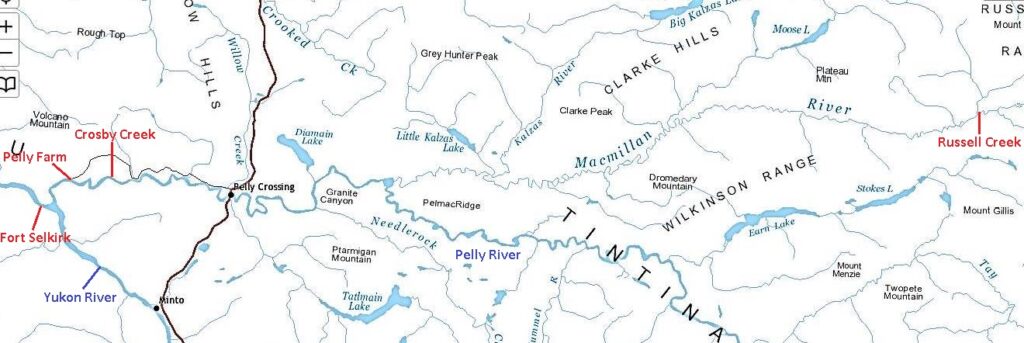

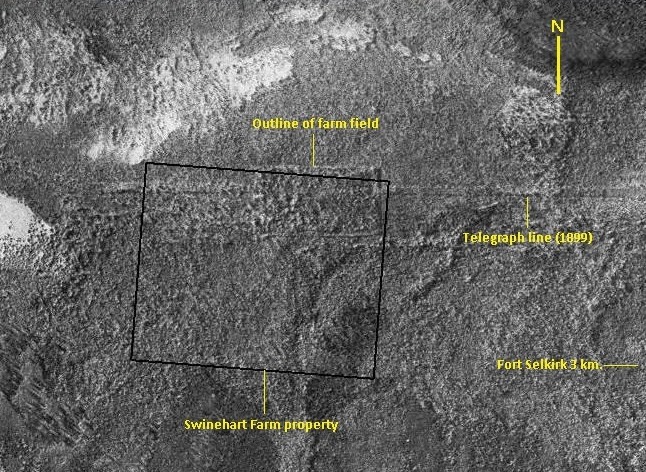

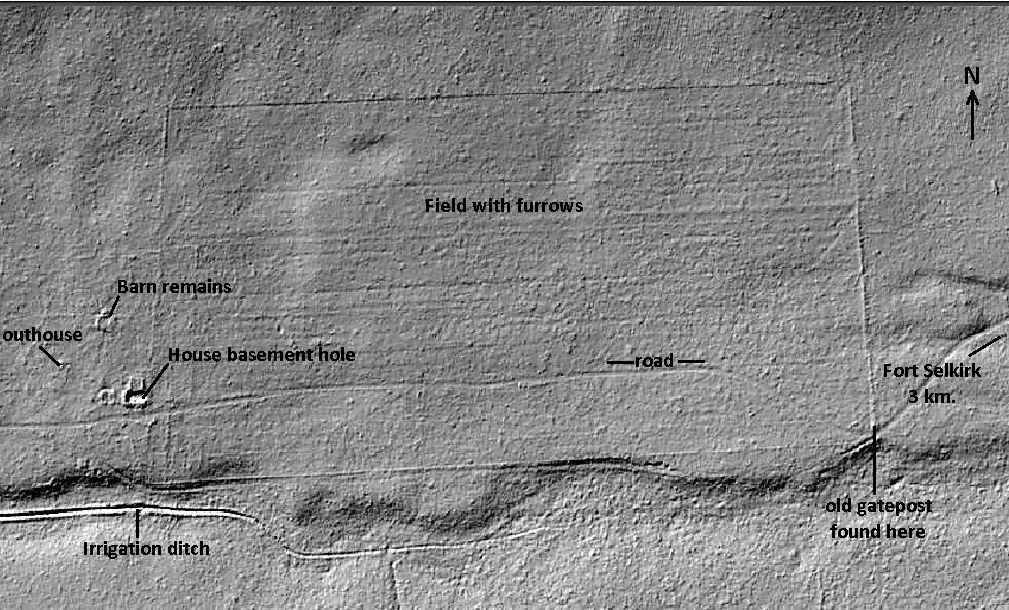

Bill’s letter touched on a few interesting subjects such as the old Pelly Crossing roadhouse and the Swinehart Farm, located in the bush about three kilometers to the west of Fort Selkirk. I was researching that farm and other topics in the area and thought there might be a chance that Bill had descendants with more information and perhaps pictures from his time in the Fort Selkirk area.

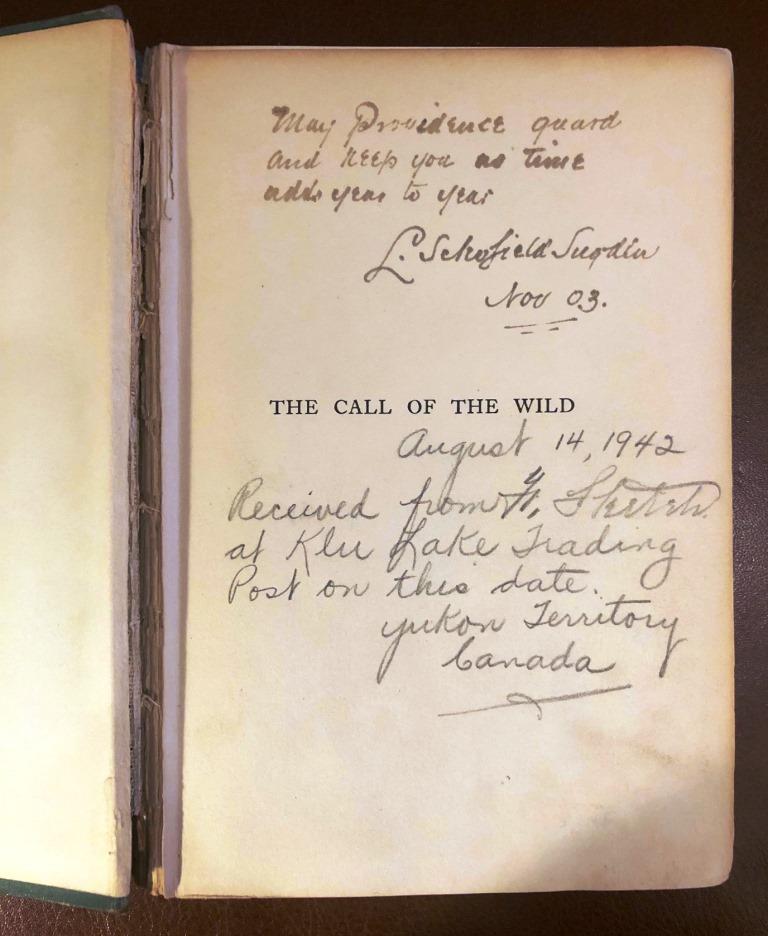

After some effort and luck, I managed to contact Bill’s grandson, Robert (Bob) Moles, of Bellingham. This initiated an exchange of information, with Bob generously sharing his family’s history in the Yukon along with photos of their life here. It also resulted in this material being deposited in the Yukon Archives in 2017 to go along with information that Bill and his wife Frances had sent there in 1979.

In September 2019, I met Bob Moles and his sister Kathy Gustafson, along with their spouses and another couple, when they came to the Yukon to explore some of the Watson family history. This took them first to the Yukon Archives to look at the information and photos that they and their grandparents had placed there.

The group also visited Carcross and the Matthew Watson General Store that had been owned and operated by Bob and Kathy’s great-uncle Matthew Watson. They then went to Champagne to see where their grandmother Frances (Kipp) Watson had provided nursing care during the influenza epidemic in 1919.

Finding Bill Watson’s 1974 letter to the Bradleys and my subsequent contact with Bob Moles ended up revealing a number of interesting and interwoven stories about the Watson family coming to the Yukon and their lives here. What follows below are a few of these stories.

The Matthew Watson family – from Scotland to the Yukon, 1887-1899

Matthew Watson (born 1863) and Martha Grace Caithness (born 1865) were married in 1884 and lived on the east coast of Scotland. Their first two sons were born there, Matthew Jr. in 1885 and John Bruce in 1887.

In November of 1887 the family left Scotland and settled in Boston, where two more sons were born, the first named William, who died at 14 months old in 1890. The next son was born in 1892 and also given the name William, and 82 years later he would write the letter to the Bradley brothers at Pelly River Ranch.

In 1893 the Watson family moved west to Tacoma, Washington, where Matthew Sr., a sheet metal worker by trade, went into business. Matthew and Martha’s daughter Grace was born in Tacoma In 1896 .

In 1897, when news of the Klondike gold discovery arrived in Washington, Matthew Sr. headed north, taking with him Matthew Jr., not yet twelve years old. After sailing up the coast, they went through to Dawson, presumably by the Chilkoot Trail and then by boat down the Yukon River system. By that fall, with fears of a famine in Dawson, like many other people Matthew and his son got out before winter set in.

They settled in Dyea, Alaska, at the start of the Chilkoot Trail, where Matthew Sr. established a tinsmith shop to meet the demand for wood stoves and other metal fabrications. He also sent for the rest of his family in Tacoma, and in late January of 1898 Martha and her three other children, Bruce aged nine, Bill aged five, and Grace, 15 months old, left Washington. Martha also had to bring along a supply of hardware that Matthew Sr. required for his business. After a very rough trip on an overcrowded steamship, they arrived in Dyea on February 2, 1898 to join Matthew Sr. and Jr.

The Watsons stayed in Dyea for the remainder of 1898 and made plans to go over the Chilkoot Pass the following spring. They would take the tinsmith equipment and supplies and look for opportunities in Atlin, the scene of the latest gold stampede after discoveries made near there the previous summer.

Martha Watson’s Diary, 1899

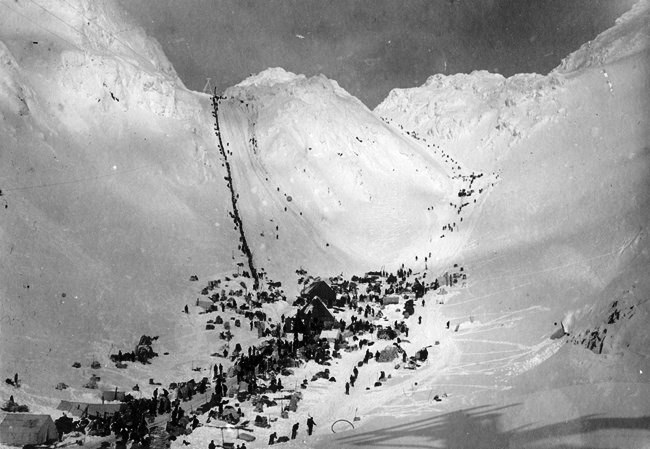

The Watson family set off from Dyea on March 10, 1899, an ensemble consisting of six people, a horse and two dogs. Despite having three children under 12, one of them only two years old, Martha managed to keep a diary of the trip to Atlin. Her description of their journey paints a picture of the challenges as well as lighter moments they had along the trail.

To get their supplies and equipment up the steep section of the Chilkoot Trail leading to the summit, the Watsons sent most of it over the aerial tramline that was then in place. They only had to carry their clothes with them, but the trip up to the summit presented its challenges. They started out with the horse pulling a sleigh up the hill with little Grace in it, and the following is Martha’s description of that: [The horse] went by spurts about twenty yards at a time and every time he stopped it took three of us to … keep the sled from coming down again. We had not reached half way when the horse fell and began to roll down. I thought for a minute he was to go to the bottom. [Matthew] Sr. had the hardest work to hold him. If the rope had broken we would have been minus our horse. Whenever he fell, Matthew [Jr.] cut the sled loose, while Bruce and I held it. … We were all in a flurry.”

(National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, KLGO Library SS-32-10566)

Martha managed to keep Grace and young Bill out of the way of this chaos, and luckily two men soon came along and helped them get the horse up the rest of the way to the top. On the steep descent down off the summit to where the Watsons’ goods were piled at the end of the tramline, Martha took a tumble while hanging on to the sled carrying Grace. In her words, “… I lost my footing. I still held onto the rope attached to the sled but I was quite a little while before I got my feet again.” Her diary the next day reads: “I did not sleep well. My limbs ached so and when I got up in the morning my face was swollen so bad I could hardly open my eyes.”

From the tramline it took a few days to relay all their goods in four to five hundred pound loads to Lake Lindeman, six miles from the end of the Chilkoot Trail at Bennett Lake. The days spent there allowed them to participate in an enjoyable evening of music and dancing with all seven ladies of Lindeman and about twenty men.

The family’s planned departure from Lake Lindeman was delayed a couple of more days by a snowstorm. They had the foresight to keep a shovel in the tent with them so they could dig themselves out the next morning.

On March 31 they arrived at Bennett, staying there one night before beginning the journey to Atlin. Their route is not clear from Martha’s diary, but it appears to have been along the ice of the lakes (Bennett, Nares, Tagish and Atlin). However, there is one reference to them being on an Otter Lake.

At Bennett they began a routine that, as interpreted from the diary, had Matthew Sr. and Jr. relaying their goods, which were divided into four loads and presumably pulled by the horse. They would take a load as far as they could go in a day, usually around 20 miles, and cache it. Martha and the other three children, perhaps with one or more dogs (they had three by this time), would haul the camp and their personal necessities to the cached goods or as close as they could manage.

They would pitch their 12’x14’ tent, either on the ice or nearby shore, and then for the next day or two Matthew Sr. and Jr. would go back and retrieve the rest of the goods they had left behind. While waiting for the two Matthews to do their relay trips, Martha would get to work preparing food for the next few days of the journey: “Made 12 loaves and a big mess of beans, rice, apricots and prunes, enough for two days (dog food always included)”.

Martha seemed quite proud of the stove that her husband had made for her: “My stove bakes just the very nicest. [Matthew] Sr. made it just to suit me. It is quite large, having four holes on top and lots of room to spare”. When cooking on the lake ice, the heat of the stove would naturally melt the ice underneath and form a puddle. The stove was evidently on legs of some sort and one time when little Grace was standing by it to get warm, her feet slipped and she slid almost completely under the stove into the icy water and had to be pulled out.

On one occasion after the two Matthews had started out hauling the loads ahead, Martha packed up the camp and her children and started walking, but she just couldn’t make it the planned distance: “I came down with the headache. It took [Matthew Sr.] to throw up the tent and me to throw down the bed and get in. I was so sick. I asked Bruce to find me a basin and when he brought me a pie plate, sick as I was, I had to laugh”.

There were a number of mishaps and unforeseen incidents along the way, including one where 13-year old Matthew Jr. had to walk over 40 miles back to Lindeman Lake for a forgotten item. On his return, darkness overtook him 10 miles from the family’s camp and the dogs brought him the rest of the way. Martha’s diary tells about this and other episodes with a tone of both humility and pride.

On April 15, a little over two weeks on the trail from Bennett and more than a month after leaving Dyea, they arrived at Atlin. The Atlin Claim newspaper learned of the family’s adventure and published an article called “Martha’s Story – A Woman Stampeder”, with the following excerpts:

“If Martha Grace Watson wondered why she was floundering in ice and snow on the Chilkoot Trail with four children aged 2 to 13, no one ever knew. If she had misgivings about the strange journey she was on, she hid them beneath an amazing sense of humor.”

“Martha trudged on, though, sometimes as far as [22 miles] a day, in spite of aching limbs and eyes swollen from the strain of bright sun reflecting from the snow. She kept little Grace in sight and gave young Bill an occasional boost along the trail. It would not have occurred to Martha to turn back, and in the middle of April 1899, she and her family walked off the ice and onto the streets of Atlin City.”

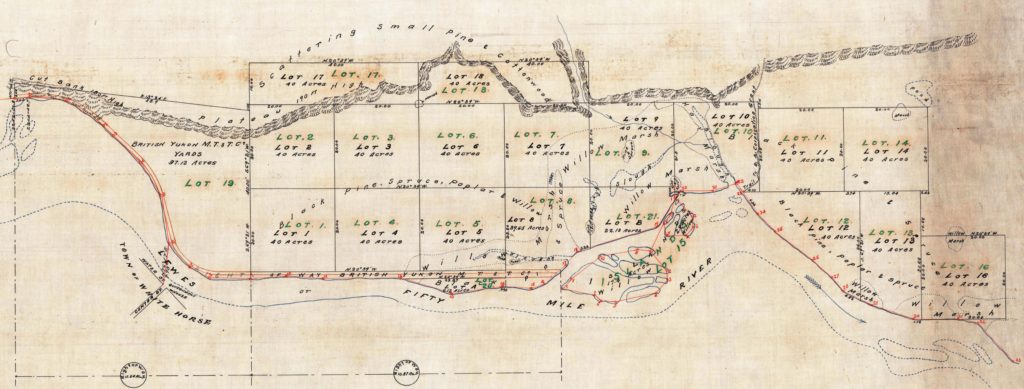

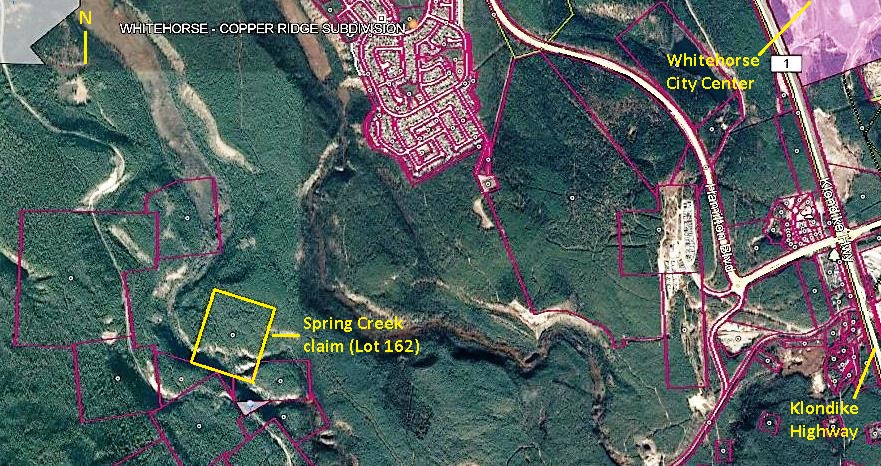

The Whitehorse Years, 1900-1923

The Watson family stayed in Atlin over the summer of 1899, then returned to the coast in the fall. How they made this trip is not mentioned in their family account. In the 1900 U.S. Census the family was in Dyea and at some point that year they moved to Whitehorse. They went on the newly-built White Pass & Yukon Route railway to Bennett, then by boat to Carcross, and again by train from Carcross to Whitehorse. The boat portion of the move was required because the section of the railway along Bennett Lake required considerable blasting work and the Carcross-Whitehorse section was completed almost two months ahead of it.

In Whitehorse, the Watson family first lived in a tent at the corner of Main Street and Second Avenue. Matthew and Martha’s fourth son, Charles, was born in this tent in January 1901, and a fifth son was added with the birth of Kenneth in December 1904.

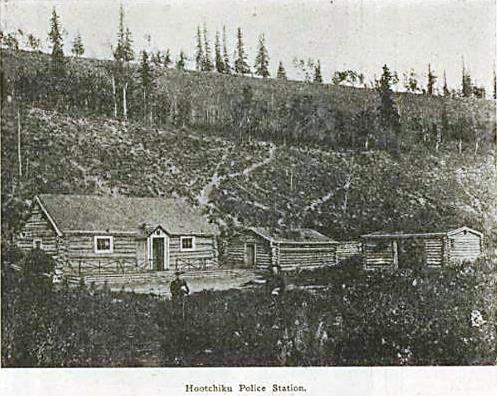

(Yukon Archives, E.J. Hamacher Fonds, #691)

Matthew Sr. had set up a sheet metal shop to make his living, but in the spring of 1904 he sold the business. This may have been to enable him to gear up for gold mining on Burwash Creek in the Kluane region, which he and Matthew Jr. did in 1905. He also reopened a metal shop in Whitehorse in the summer of 1905, while. Matthew Jr. continued mining on Burwash Creek until at least 1909, the success of which is not known.

Sometime during this period, upheaval came to the Watson family due to Matthew Sr.’s drinking. He left the family and the Yukon, but before doing so he tried to talk Bill, apparently his favorite son, into going with him. Bill, then in his early teens, chose to stay with his mother, knowing it was going to be difficult for her to support all the children.

Martha had a house at Second Avenue and Elliot Street and took on an active life of volunteer service and hosting events. Newspaper articles indicate she was very involved in this way, particularly during the First World War when she raised funds and organized care packages for Yukon soldiers overseas.

Some of Martha’s children appear to have acquired musical abilities, perhaps derived from her, as she loved to sing. A brass band called The Whitehorse Band was formed about 1907 and the three oldest Watson brothers, Matthew Jr., Bruce and Bill, all became members. Matthew Jr. played the trombone, Bruce the trumpet, and Bill was a drummer. A number of prominent Whitehorse people were also members of the band.

(Watson family collection)

In late 1911, Martha’s oldest son, 26-year old Matthew Jr., purchased a general store in Carcross from Frank McPhee and gave the business his own name. By this time, Martha’s next two sons, Bruce and Bill, were both telegraph operators, jobs they began in their teens. Her daughter Grace would soon go out to Vancouver to attend nursing school. The two sons born in the Yukon, Charles and Kenneth, were still in school in Whitehorse.

Norma Joins the Family, 1912

An article in the Whitehorse Weekly Star on January 5, 1912 described the tragic death of Idelle Cochran shortly after she gave birth to a baby girl at a mine in the Wheaton River area, west of Carcross. This tragedy followed a previous one in April 1910, when another daughter died at the age of six. Idelle and her three daughters had been travelling up the coast by steamship to join her husband Howard at Carcross when the little girl suddenly became sick and died two days before reaching Skagway.

When Idelle died on December 27, 1911, Howard had to leave the two older daughters, aged 13 and 10, with the baby and their deceased mother while he went 10 miles or so by dog team to the nearest neighbors for assistance. The newspaper article states that a few days later, Howard and his three daughters, along with his wife’s body, arrived by train in Whitehorse, where the five-day old baby was handed over to Martha Watson to care for. The next day a funeral was held for Idelle Cochran, followed by her burial in the Pioneer Cemetery.

The Watson family lore provides additional details, some of them different from the newspaper article, about the Cochran baby girl coming into their lives. Their account says that Matthew Watson Jr. was woodcutting in the bush when he encountered Howard Cochran with three girls, one of them a newborn, and the body of his wife in his sled. Howard was desperate about what to do and Matthew told him he would get the baby to his mother to take care of. Matthew got to a place, likely the Robinson flag station on the railway, where he could send a telegraph message to Martha in Whitehorse, telling her to meet the train there. When she got to the train station, the conductor put the baby in her arms and Martha took her home.

Another newspaper article on May 24, 1912 reported on a visit by Howard and his two older daughters to Whitehorse, where they visited Martha Watson and the baby girl. They found her to be “getting along nicely and developing into a beautiful child”.

Sometime after leaving his daughter with Martha, Howard returned for her, saying that his other daughters could take care of her. Before long he was back and asked Martha to keep the baby for another six months because his girls couldn’t manage it yet. She did this and Howard later returned for the baby. Once again, however, he brought the baby back for Martha to take care of, except this time she said she couldn’t stand to give her up again and would only take her if she could adopt her. Howard realized he had little choice and agreed to give his daughter to Martha. This girl became Norma Idelle Watson, a new daughter for Martha Watson, now 47 years old, to raise along with her other children.

(Watson family collection)

In the fall of 1920, Martha along with Norma and her two youngest boys, Charles and Kenneth, left the Yukon to live in Chilliwack, BC. They moved into a house across the street from the Kipps, a pioneer family of the Chilliwack area. This was undoubtedly pre-arranged because Martha had already met her future daughter-in-law from the Kipp family.

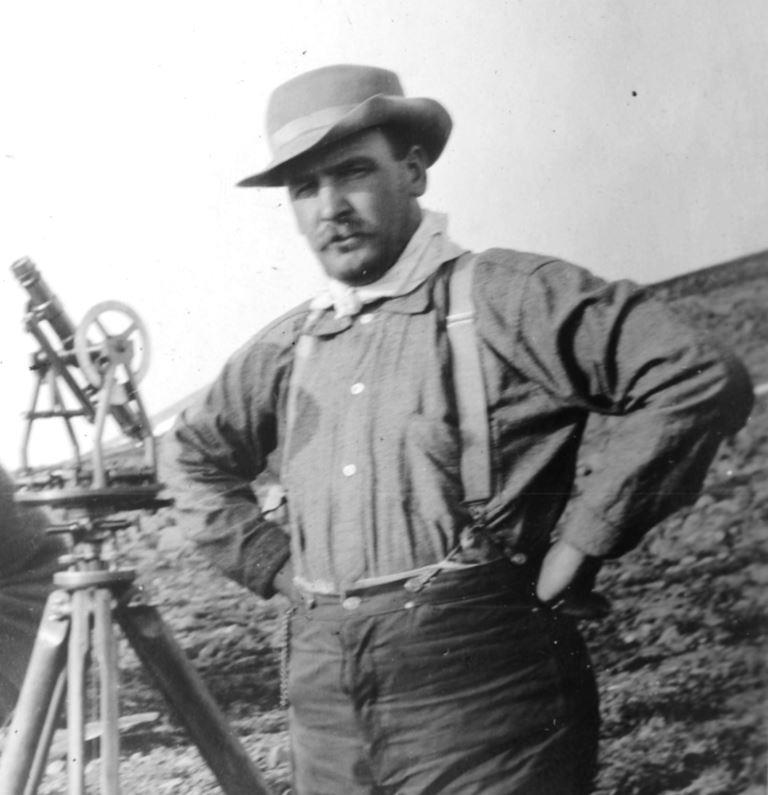

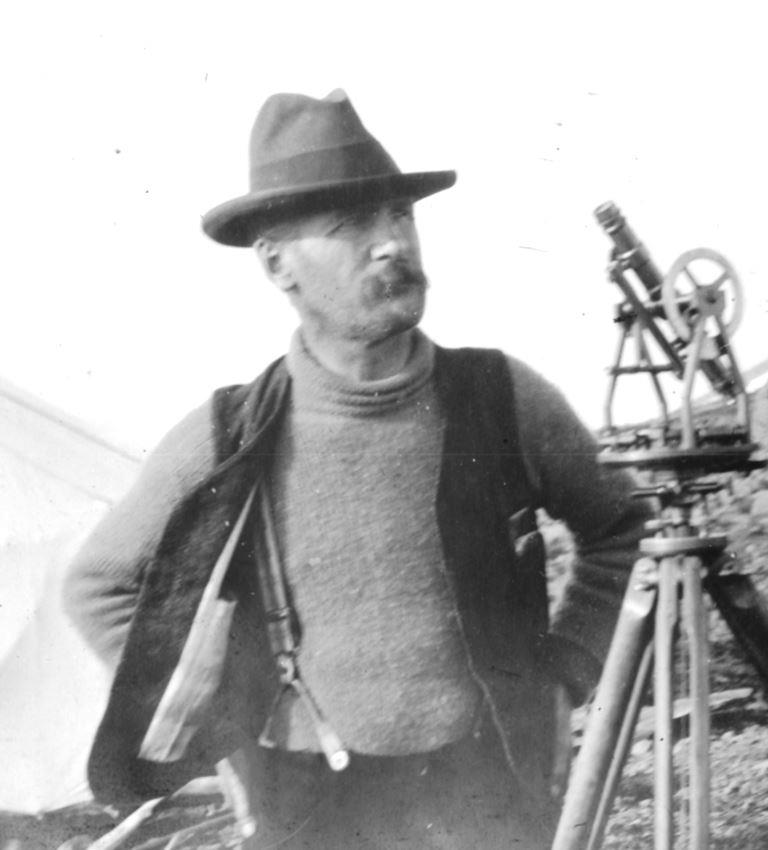

Bill Watson and Frances Kipp, 1911-1923

Bill Watson’s 1974 letter to the Bradleys at Pelly River Ranch mentioned the Swinehart Farm near Fort Selkirk. It had been established by William Swinehart in 1898 and existed until his death in 1914. Bill had obviously visited the farm “… in a valley where they grew almost anything they needed.” In July 1911 he attended the wedding of Swinehart’s youngest daughter Rhoda at Fort Selkirk and appears in wedding photos of that event.

Bill was only at Fort Selkirk for one year, but he established a friendship with one or more of the Swinehart family members. More than ten years after his time at Fort Selkirk, he sent pictures from his wedding to them. By 1927, when Bill was living in Washington, all the Swineharts who had been in the Yukon had moved to California. How long they and Bill continued to communicate, and undoubtedly reminisce about their Yukon days, is not known.

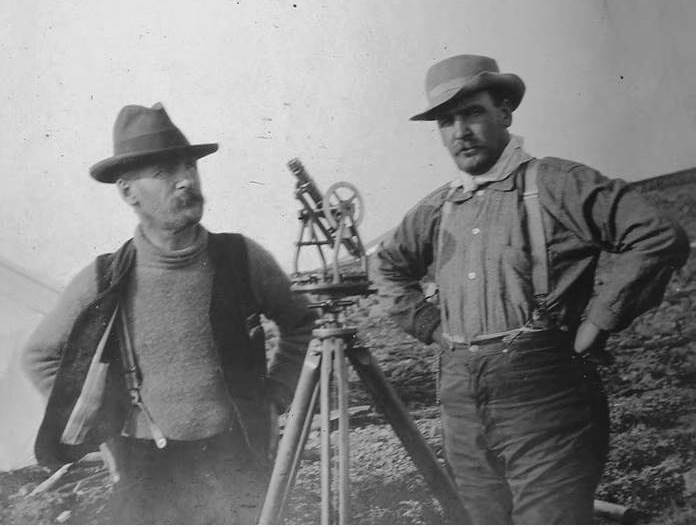

From Fort Selkirk Bill went on to be a telegraph operator in Whitehorse, but in 1915-16 he did a stint at Lower Laberge. He was sent to replace the operator there who liked his drink too much.

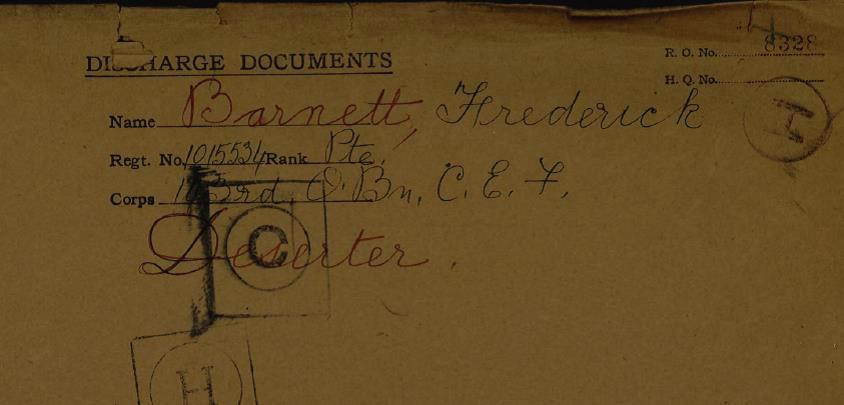

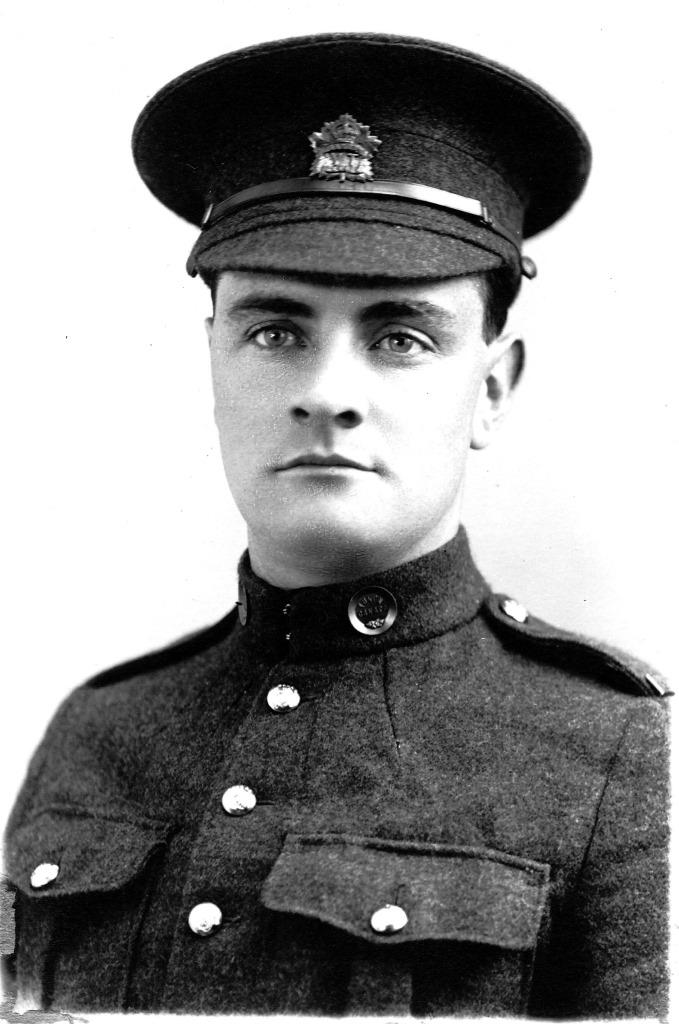

(Watson family collection)

In October 1916, Bill Watson enlisted in the Canadian Over-Seas Expeditionary Force to serve Canada in the First World War. On his way ‘outside’ for training, he stopped in Vancouver to visit his sister Grace, who was in nursing training. When it was time for Bill to leave, Grace saw him off on the train, and along with her was her friend Frances Kipp.

(Watson family collection)

In 1918, while Bill was overseas, Frances Kipp was in her senior year of nurse training at Vancouver General Hospital. That year the Spanish influenza epidemic broke out, killing millions of people worldwide. Frances witnessed her roommate dying within the course of a day and saw two children on a street trying to wake up their dead parents. The surgical unit where she worked was closed except for emergencies, and schools were made into makeshift emergency wards.

When she graduated in the spring of 1919, Frances was pondering her future and knew she wanted a change from the tragedies she had seen. She responded to a posting of a nursing vacancy at the Whitehorse hospital and got the position, much to her surprise. In the evening of April 9, she was aboard a steamship and on her way to the Yukon.

In Skagway, before boarding the train, she put on a new suit to make a good impression when she arrived at the station in Whitehorse. About a mile out of Whitehorse, the train came to a halt and two Royal Northwest Mounted (RNWMP) policemen came aboard and announced that all passengers from Vancouver would have to get off. As there was no influenza yet in Whitehorse, the more than 100 passengers from Vancouver were quarantined for eight days at the police barracks. This was Frances’s introduction to Whitehorse, but she was treated well and looked very nice in quarantine in her new suit .

(Watson family collection)

Frances started work in late April 1919 at the hospital, built in 1915 at Second Avenue and Hanson Street and with a staff of one doctor and two nurses. It was relatively quiet when she started, but that changed for her after a month. A message came from Champagne that many of the First Nation people there were sick, and Frances was asked to go and see what could be done. It was now late May, a month into her first real job, and she was about to have a nursing experience in the Yukon that she undoubtedly never envisioned.

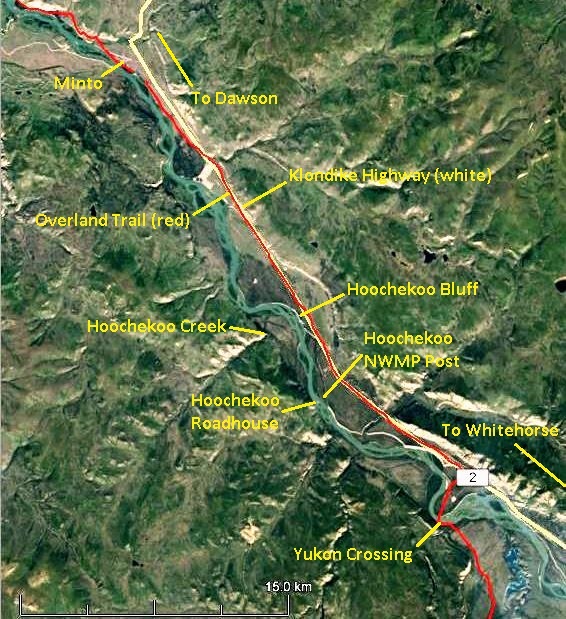

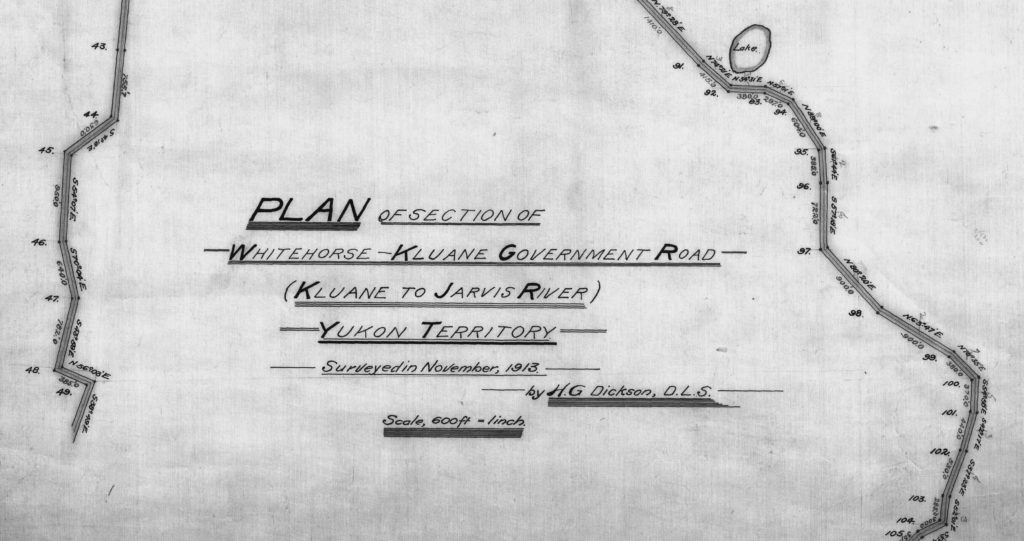

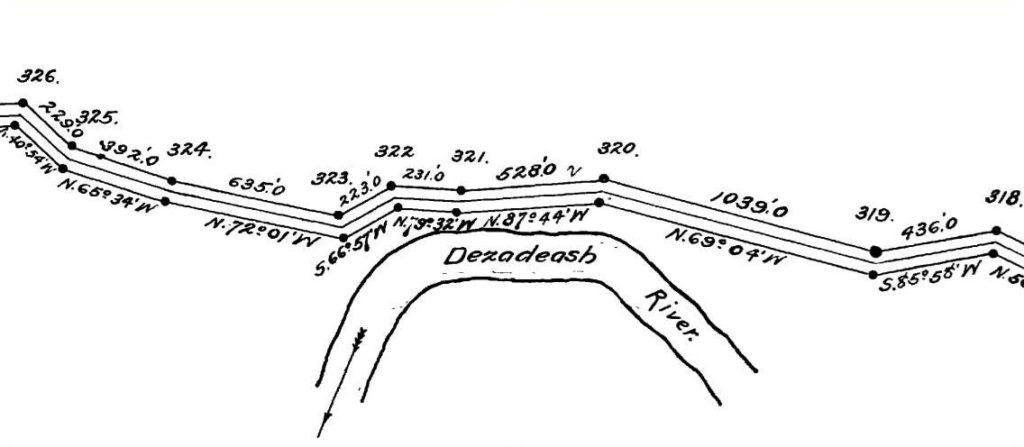

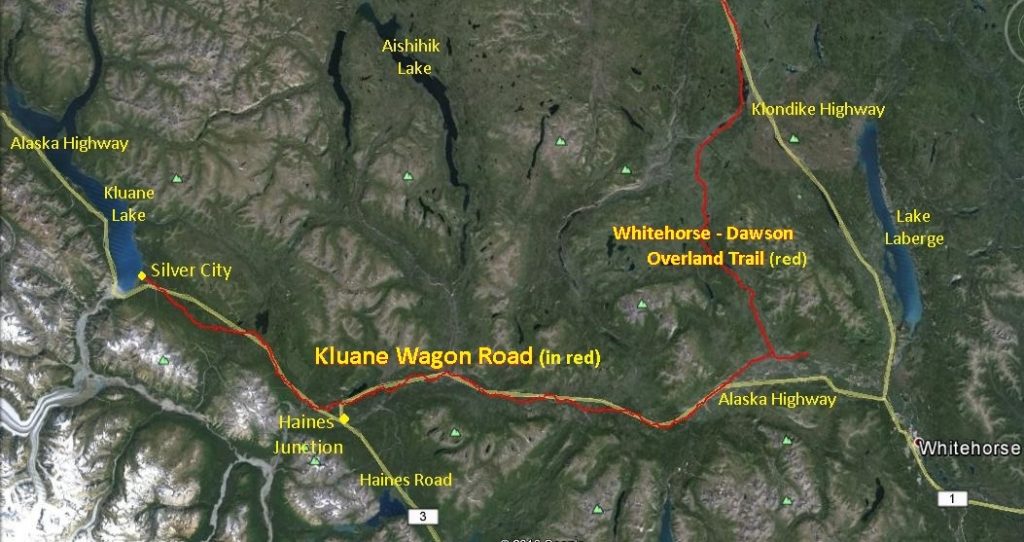

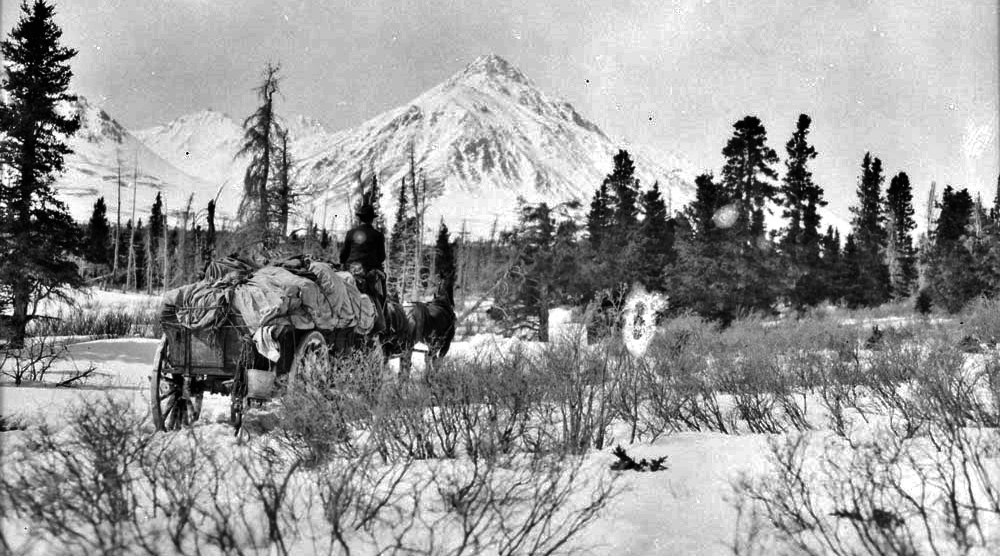

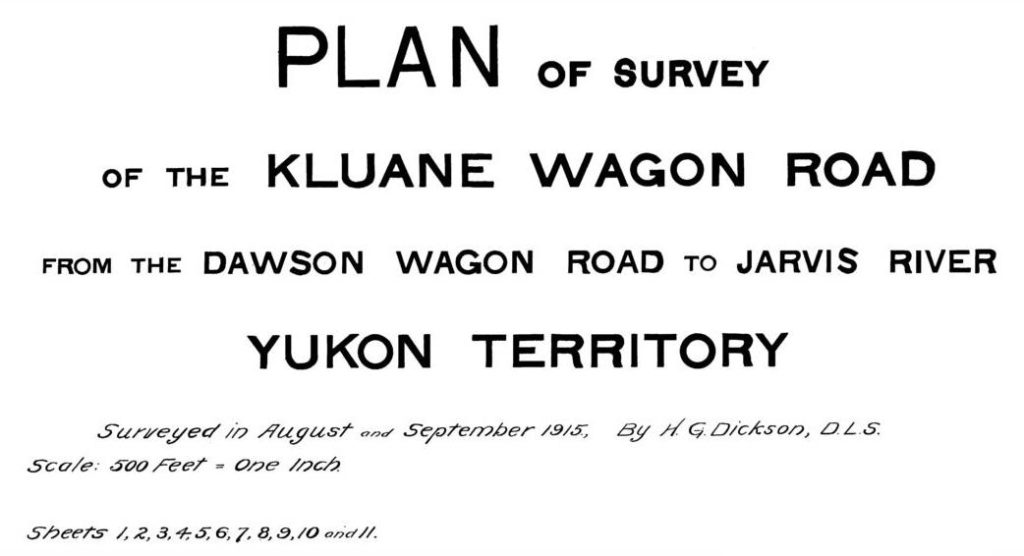

An open-topped Ford car was loaded up with Frances, a man to cook for her, a RNWMP member, and some groceries including a box of fruit, a luxury at that time, and a quarter of beef strapped to the back of the car. The 64-mile trip, first on the Whitehorse-Dawson Overland Trail and then on the Kluane Wagon Road, took eight hours due to time spent filling holes in the road and clearing it of fallen trees and brush.

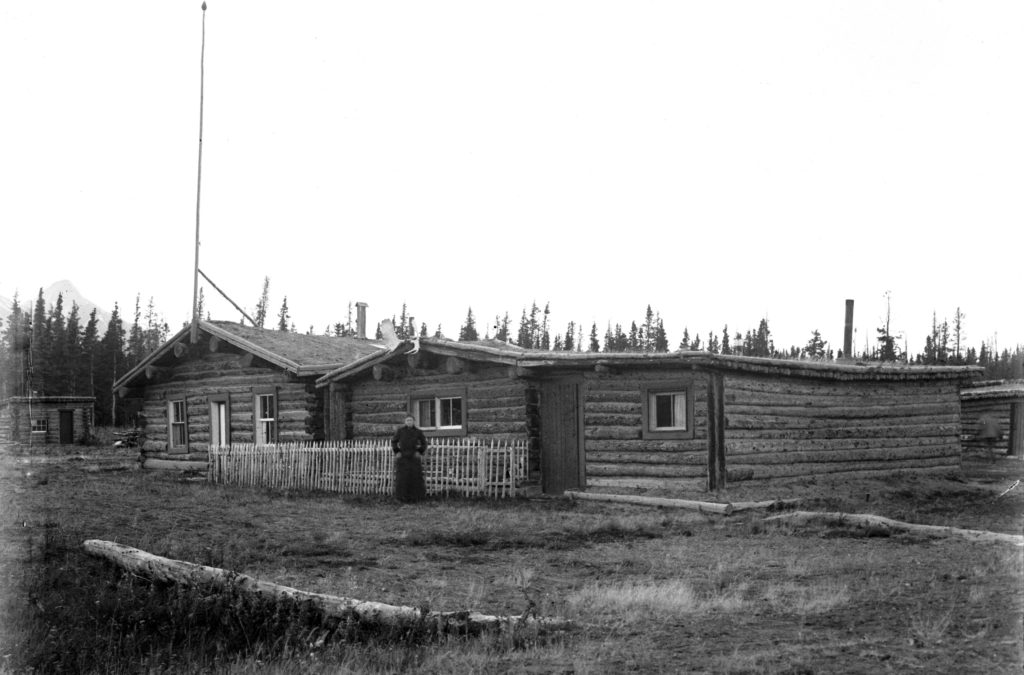

In Champagne Frances was given use of the police sergeant’s cabin, which was very comfortable and located next to the Kluane Wagon Road and eventual Alaska Highway. She took her meals in Harlan (“Shorty”) and Annie Chambers’ roadhouse, a short distance away.

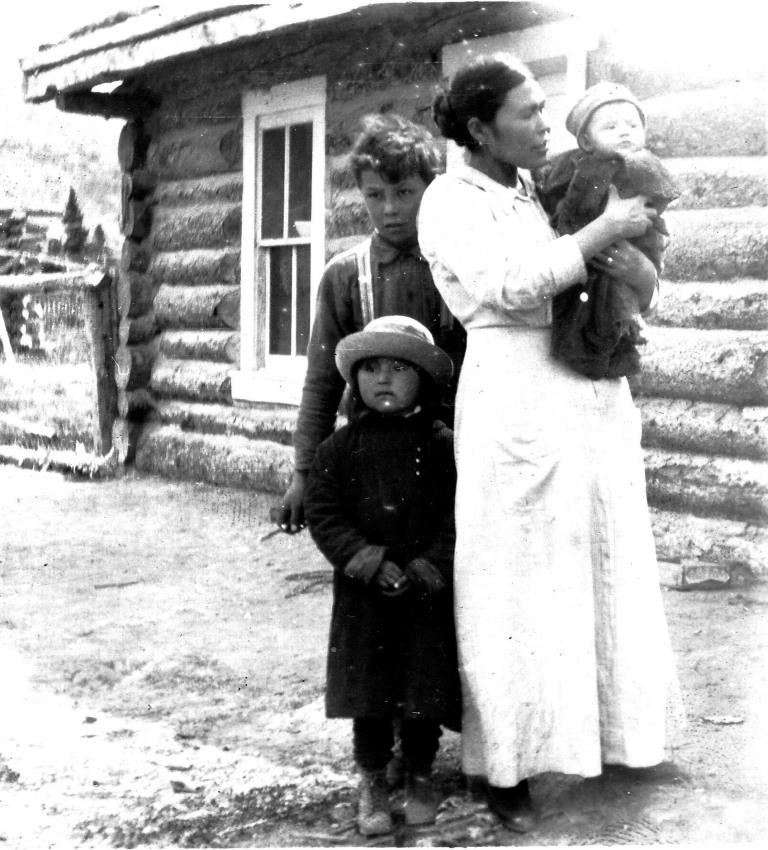

(Watson family collection)

(Watson family collection)

When Frances went to size up the influenza situation, she found it very distressing, with about 40 people sick. There was one elderly couple that she knew would not make it, and three days later they died. The next day she attended their funeral and burial in the Champagne cemetery, and later that night attended a potlatch where the people expressed their grief and had a feast.

Frances’s happier stories from her time at Champagne included helping a 10-month old girl who was very ill with pneumonia to recover by sponging her and holding her to keep mustard plasters in place that were part of the treatment. She also witnessed the birth of a baby girl and was impressed by the care given both mother and baby by the attending women.

Frances was quite busy in Champagne, but she managed to take some photographs that included buildings and people. One of the photos had Annie Chambers in it, the first picture that her grandson Ron Chambers said he had ever seen of her. Before leaving, Frances also took a group photo that included some Chambers family members and others at Champagne. She was relieved by another nurse and the open-topped Ford car took her back to Whitehorse.

(Watson family collection)

(Watson family collection)

Frances was aware years later that Shorty and Annie Chambers’ daughter Ida, who was eight years old when Frances nursed in Champagne, went to Vancouver and attained a nursing degree. Ida became the first Yukon First Nation woman to become a registered nurse, and went on to become Charge Nurse of the Operating Room at Vancouver General Hospital. Perhaps Frances’ work at Champagne planted a seed with Ida to pursue this career.

In the following spring of 1920, the influenza struck at the Chooutla school in Carcross and Frances was asked to attend. It was described as an emergency and there were no trains scheduled for a few days. After much discussion about how to get her there, a message finally came from White Pass headquarters in Skagway for one train engine and a car to be readied to take Frances to Carcross. She then went as the only passenger on an unscheduled train ride, and years later she said it had felt like she was on Air Force One.

At Carcross, she found everybody sick, teachers and children both. The family account doesn’t say how she administered to them or for how long and what casualties, if any, resulted from the sickness there.

In June 1919, Bill Watson returned from overseas, where he had served in the war as a motorcycle dispatch rider and then stayed on an additional six months after the war in Germany with the ‘army of occupation’. In Whitehorse he resumed his career as a telegraph operator with the White Pass & Yukon Route railway.

(Watson family collection)

Frances had become engaged to a man in Whitehorse and they were making wedding plans. He had to leave the Yukon for work reasons and while away he contracted the influenza and died. A telegraph message was sent to notify Frances, and the person that delivered it to her was Bill Watson, who she would later marry. It seemed that the influenza defined Frances’ life in the Yukon, both professionally and personally.

(Watson family collection)

In November 1921 Bill and Frances went out to Chilliwack, where both their families were living, and were married in the Kipp family home on January 2, 1922. They returned to Whitehorse and in November of that year their daughter Dorothy was born. Frances had poor health during the first year of her married life, and that along with wanting a warmer place to live prompted them to move to Chilliwack in late 1923, and not long after that to Washington.

After the Yukon

According to a newspaper article, Matthew Watson Sr., who had left his family due to issues with alcohol, returned in 1910 to visit after being away for three years. The family account makes no mention of this, instead stating that he was never heard from again after leaving. Records show that in 1913 he was a sheet metal worker at a mill in the Vancouver area. Years later his daughter Grace, by then a nurse in Seattle, discovered that her father had died in San Francisco and was buried there in a pauper’s grave.

After moving from the Yukon to Chilliwack in 1920, Martha Watson moved on to Vancouver in 1926. She made trips back to the Yukon in 1935, 1945 (her first airplane ride, at age 80) and 1951 to visit her sons Matthew Jr. and Bruce, who had remained there. Martha died in Whalley (Surrey) in 1957 at the age of 92 and is buried in the Burnaby Heritage Cemetery.

Norma Cochran, who came unexpectedly into the Watson family as a five-day old baby in 1912 and was adopted by Martha, went on to become a school teacher, get married in 1934, and live in several places in British Columbia. She named a daughter Idelle after her birth mother.

Bill and Frances Watson, along with their daughter Dorothy, son-in-law Robert Moles Sr. and granddaughter Kathryn, also returned to the Yukon in 1965 for a visit. Bill and Frances lived the remainder of their lives in Bellingham, with Bill passing away in 1984 at age 92 and Frances in 1990 at age 95.

100 years after Frances provided nursing care at Champagne and Carcross, her daughter Dorothy (Watson) Moles was living in a nursing home in Bellingham, Washington, where she contracted the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in early April 2020. She appeared to have beaten the disease, but developed complications that were likely a result of it, and passed away on May 2, 2020 at the age of 97.

Today, there are no Watson family descendants remaining in the Yukon as far as I have been able to determine.

Exploring Yukon Roots, 2019

Bob Moles’ family history trip in September 2019 took him and his wife Julie and their friends Steve and Lynn Mayo to Kwäday Dän Kenji (Long Ago Peoples Place) near Champagne for a tour. This was hosted by Harold Johnson and Meta Williams, who built and operate this one-of-a-kind First Nation heritage and education facility. There is a good chance that Harold and Meta had ancestors who were tended to by Bob’s grandmother Frances Kipp (later Watson) in Champagne during the influenza outbreak.

previously while nursing at Champagne.

(Gord Allison photo)

Bob and company went on into Champagne to see the community where his grandmother had provided nursing care during the epidemic of 1919. They then spent a few days in the Haines Junction area, mainly sightseeing and fishing with Ron Chambers. Ron and Bob stood together for a photo 100 years after Ron’s grandfather Shorty Chambers and Bob’s grandmother Frances Kipp posed together in a picture at Champagne.

(Gord Allison photo)

After 10 days in the Yukon, Bob Moles returned to Washington with a much greater awareness and appreciation of his family’s Yukon history and a determination to return again to explore more of it.

The information and photographs in this article and more about the Watson family’s life in the Yukon can be viewed in the Watson Family Fonds at the Yukon Archives.

Updated April 11, 2020

Updated May 25, 2020